What’s the difference between the European Union and the European Convention on Human Rights? Here’s a handy survival guide.

Later this week, the UK will decide whether to remain a member of, or leave, the European Union (EU). But that’s not the only proposed major constitutional change currently dividing politicians.

Some have also suggested that the UK should no longer be a signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). And details of the UK Government’s plan to repeal the Human Rights Act and replace it with a Bill of Rights have yet to be unveiled.

Confused?

So are a lot of the media, apparently – the EU and the ECHR are often discussed in close proximity and are frequently muddled up. So here’s a handy reminder of their origins and some important differences between the two legal systems.

First, the EU…

The EU is a political-economic union founded upon various international agreements (treaties) which aim (amongst other things) to facilitate trade between member states.

After World War II, European integration was seen to be an antidote to the extreme nationalism which had devastated the continent, and trade was an important means of establishing that integration. Initially six countries pooled their coal and steel resources, but since then the EU has grown into a union of 28 member states, setting up a common market and allowing goods, services and people freedom of movement (subject to certain restrictions) between states.

The EU has its own parliament, drawn from representatives from each member state. The European Parliament debates and produces laws on a wide variety of matters such as the environment, employment and discrimination. The EU also has its own court: the Court of Justice of the European Union, which sits in Luxembourg. This court oversees the uniform application and interpretation of European laws, in cooperation with national courts.

When the UK joined the EU in 1973, an Act of the UK Parliament (the European Communities Act) was brought in to provide a mechanism for adopting EU laws at a national level and taking account of decisions of the EU’s court.

What about the ECHR?

After World War II, twelve countries joined together to form the Council of Europe. The Council of Europe is an international organisation which aims to promote democracy, the rule of law, human rights.

The Council of Europe is totally distinct from the EU, and is not to be confused with the European Council (an EU institution that that comprises the heads of state or government of the member states) or the Council of the European Union (sometimes called the Council of Ministers, this is another EU institution which, along with the European Parliament, makes European Union laws).

The Council of Europe cannot make binding laws, but it does have the power to enforce certain international agreements. The best known enforcement body of the Council of Europe is the European Court of Human Rights, which enforces the European Convention on Human Rights.

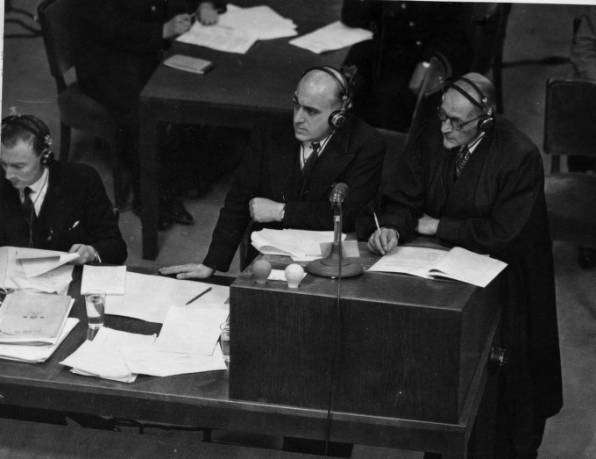

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) is an international treaty which protects human rights and fundamental freedoms. It was drafted in 1950 by the Council of Europe. A British Conservative Member of Parliament and lawyer, Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe, was a leading member of the Committee which drafted the ECHR. As a prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials, he had seen first-hand how international justice could effectively be achieved.

Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe (centre) prosecuting Nazi war criminals at the Nuremberg Trials

The drafters of the ECHR aimed to set a human rights agenda which would avoid any repetition of the most serious human rights violations that had occurred during the Second World War. The ECHR has played an important role in the development and awareness of human rights across Europe.

The European Court of Human Rights sits in Strasbourg. Now, thanks to the Human Rights Act, people can bring a Convention rights claim in the domestic courts.

Do EU law and the ECHR interact?

Yes, in some ways. Although the EU is independent from the Council of Europe, each share ideals about human rights, democracy and the rule of law uniting Europe.

Signing up to the ECHR is a (political) condition for EU membership (for new members at least). The EU also has its own Charter of Fundamental Rights, which has the same status as the union’s founding treaties. In 2007, an international agreement (known as the Lisbon Treaty) obliged the EU to ‘accede to’ the ECHR.

Learn what effect Brexit could have on fundamental rights here.

Read our explainer on the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. Read more on the European Convention on Human Rights. Take a look at our resources on the Human Rights Act and the Government’s proposal to replace it will a Bill of Rights.