The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) was the first human rights Convention of the twenty-first century.

It was opened for signatures on 30 March 2007, and on the first day 82 States signed up to it – the highest number in history for the opening day of a Convention.

What Does the CRPD Do?

Image Credit: Green Chameleon / Unsplash

Image Credit: Green Chameleon / Unsplash

The Convention doesn’t create new human rights, but it does:

- Set out what human rights – such as the rights to life and liberty – actually mean in the context of disability;

- Clarify what these rights mean for specific groups, such as children with disabilities; and

- Place obligations on governments to take active steps to make sure people with disabilities can enjoy their human rights.

What Does it Cover? How Does it Work in the UK?

Image Credit: Helena Lopes / Pexels

Image Credit: Helena Lopes / Pexels

The CRPD covers a broad range of areas including health, education, employment, discrimination, access to information, independent living, access to justice and situations of risk and humanitarian emergencies.

The UK “ratified” the CRPD (gave it effect in UK law) in 2009. The Convention reinforces the human rights protections that already exist in UK law, under the Human Rights Convention and Human Rights Act. It does this by setting out steps the government needs to take to make our society one in which people with disabilities are not prevented from enjoying those rights.

For example, Article 6 of the Human Rights Act protects the right to a fair trial or access to justice. This means we all have the right to be informed promptly, in language we understand, of any crime we’re accused of, as well as have adequate time and facilities to prepare a defence; and to have access to a lawyer.

Article 13 CRPD clarifies that ensuring effective access to justice for someone with a disability may involve providing procedural and age-appropriate accommodation if they need to attend court. Article 13 also requires states to promote appropriate training for those working in the justice system, such as police and prison staff.

Who Does It Apply To?

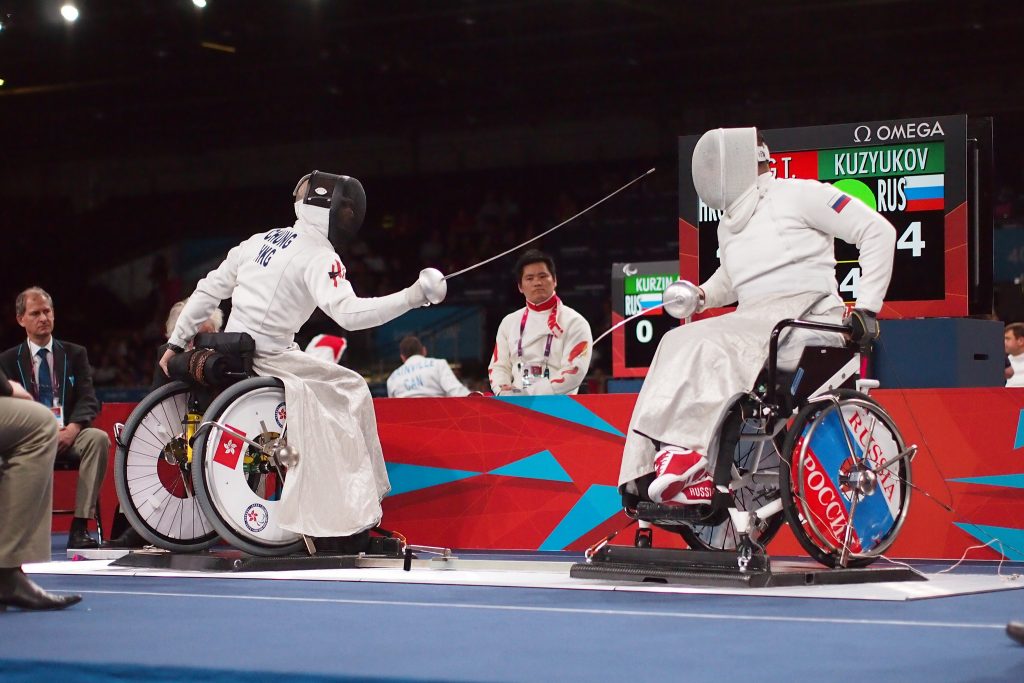

Image Credit: Farrukh / Flickr

Image Credit: Farrukh / Flickr

The CRPD doesn’t contain a black and white definition of “disability” or “person with a disability.” This is because, as it explains, disability is an “evolving concept,” and “results from the interaction between persons with impairments and attitudinal and environmental barriers that hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.”

Article 1 CRPD states that people with disabilities include:

… those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.

Right. How Does It Work?

Image Credit: Igor Ovsyannykov / Unsplash

Image Credit: Igor Ovsyannykov / Unsplash

Article 4 CRPD places general obligations on states who have signed up to the Convention to take positive steps to make sure the human rights of people with disabilities are realised.

These steps include:

- Adopting new laws and policies to implement the Convention rights;

- Abolishing existing laws and policies which discriminate against people with disabilities;

- Making sure all public authorities and institutions act in accordance with the Convention;

- Promoting the development of goods, services and facilities which are suitable for people with disabilities;

- Providing accessible information about mobility aids, support services and facilities to people with disabilities; and

- Promoting training on the Convention rights for staff working with people with disabilities.

Article 4 refers to economic, social and cultural rights. It requires each state to take serious measures to make sure these rights (which are distinct from basic human rights) are also a reality for people with disabilities.

Raising Awareness and Accessibility

Article 8 CRPD requires states to adopt effective awareness-raising measures to foster respect for the dignity of people with disabilities, to combat stereotypes and harmful practices, and promote awareness of the skills and contributions of people with disabilities.

Article 9 requires states to take steps to ensure that people with disabilities have equal access to transportation, infrastructure, facilities and services. Examples are given, such as eliminating obstacles to accessing transportation, housing, workplaces and emergency services.

The Optional Protocol

States can also “ratify” (make binding in their national law) the CRPD’s Optional Protocol. This is an extra piece of law which supports the Convention. If a state has ratified the Protocol – as the UK has – people in that state can complain to the Committee if their Convention rights have been breached. However, they can only do that if they’ve already exhausted other means of getting justice in their national courts.

Who’s checking?

Image Credit: Pawel Janiak / Unsplash

Image Credit: Pawel Janiak / Unsplash

The CRPD is monitored by the UN’s Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. This is made up of 18 independent experts.

States who have signed up to the Convention must send progress reports to the Committee every four years to show what steps they’ve taken to implement the Convention. Other bodies such as national civil society organisations can submit “shadow reports” to the Committee to ensure it gets a balanced view. Finally, the Committee publishes its “Concluding Observations,” which the state must publish and act upon.

The UN Committee published its observations on the UK’s progress in August this year. The report was heavily critical, noting two areas where it considered the UK had made progress but over 60 where it was “concerned” or “deeply concerned,” including access to education and independent living. We still have a long way to go.