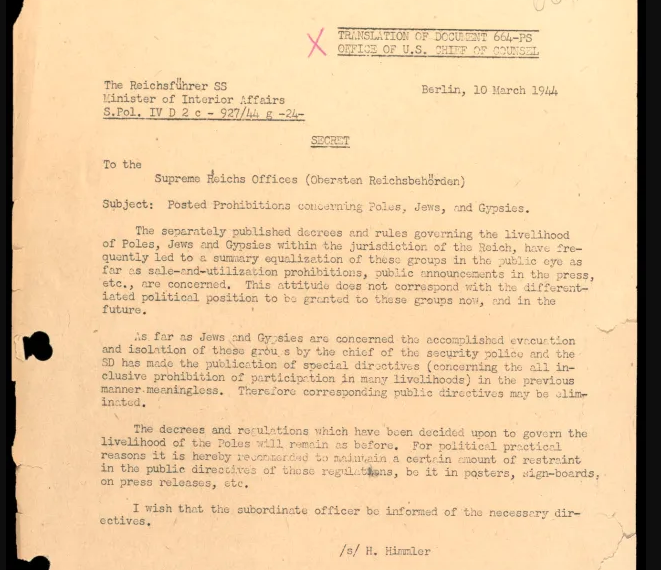

Professor Rainer Schulze from the University of Essex is a leading historian specialising in the Holocaust. In 2015, he wrote a series of blogs focusing on the commemoration of Roma and Sinti genocide for the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust.

In one, he wrote: “Commemoration is never an end in itself. In order to be meaningful commemoration needs to remember the past in order to shape our common future.

“If the Holocaust teaches us anything, it surely tells us loudly that when the human rights of one group are violated, no group can feel safe.”

How has the commemoration of the Roma genocide changed since he wrote those words five years ago?

“I must say – I don’t think it has changed at all,” he told EachOther. “In the academic circles, the … Roma are slightly more recognised as victims of the genocide.

“I am not sure how far this has travelled down to a general acknowledgement that the Holocaust affected the Sinti and the Roma.”

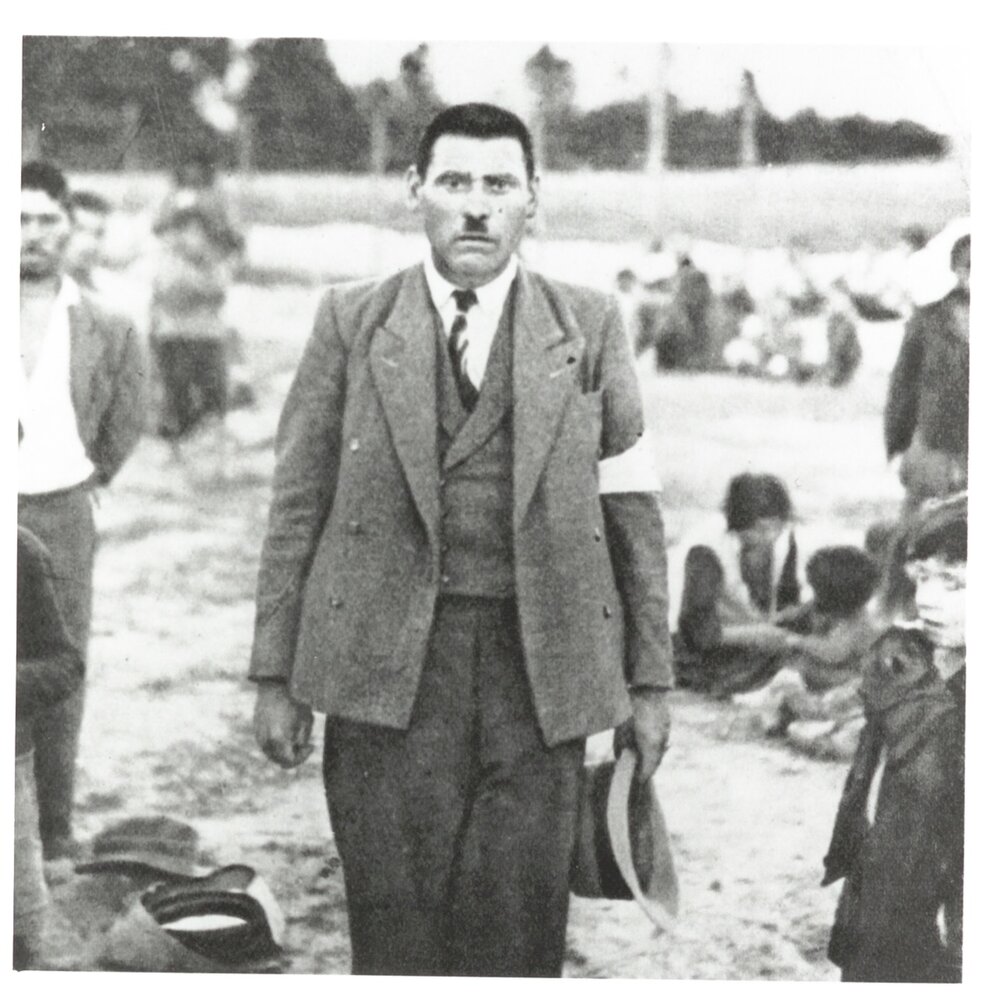

Photograph of a Roma man thought to be Jozef Kwiek. Credit: Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

Asked what needs to be done to address this, Schulze has many suggestions.

He said that there needs to be greater unity among Roma organisations. Different groups commemorate the Holocaust on different days, which may contribute to the “pitiful” levels of attendance at many ceremonies, he explained.

Roma must also have a voice at the table to decide how the Holocaust is commemorated, he added. He pointed towards the planned Holocaust memorial in London’s Victoria Tower Gardens and how, at present, there are no Roma people on its decision-making board.

Thirdly, coalitions must also be formed between minority groups – including Jews and Muslims – to fight for greater representation within all political parties, he added.

Furthermore, more role models are needed in order to challenge negative stereotypes, he said. “Many GRT are still relatively hesitant to identify themselves as such. They could suffer disadvantages, personally or professionally. We need more role models to show that Roma can be everything they want to be,” he said.

Lamenting the slow recognition of the Roma genocide, Schulze told EachOther he feels “pessimistic”.

“To be perfectly blunt, mainstream society even today do not really know about the Roma.

“The discrimination continues. Not in the same way as the 1930s and 40s. Much of the vagrancy laws responsible for their legal persecution are no longer there.

“Other than that, anti-Roma racism is pretty much acceptable.”

- The Forgotten Victims exhibition at the Wiener Holocaust Library, in London, is open until 11 March 2020.

- The Home Office consultation on granting police new powers to criminalise trespassing and end “unauthorised encampments” ends on 4 March. Human rights group Liberty has developed a tool to help you respond to it. Find it here.