History has never had the best human rights record. After all, it’s the reason they were formally agreed upon in the first place.

After the grim atrocities of the Nazis in World War II, the globe united to ensure such violations could not happen again. These were officially recorded as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which, among other things, protects us against discrimination, torture, and slavery, while safeguarding our right to privacy, a family life, and free speech.

There’s still much work to be done around the world to make sure everyone has these basic rights, but over the centuries we have undeniably come a long way. But what do we do about the less than savory remnants of our past that still linger all around us in the form of statues, monuments, and buildings?

An issue thrown into deadly focus

Image Credit: Bob Mical / Flickr

It’s an issue that’s been thrown into deadly focus this month after protests about the removal of a statue of Robert E Lee in America turned ugly. The Confederate Army General is now widely seen as a figure of slavery and racism, but the resulting protest over the city’s decision to remove the statue left one young woman dead.

The debate has now crossed over to this side of the Atlantic too, as former barrister and journalist Afua Hirsch writes in the Guardian that perhaps Nelson’s column in London should be next to go. “You would now call [him], without hesitation, a white supremacist,” the piece reads. “While many around him were denouncing slavery, Nelson was vigorously defending it. Britain’s best known naval hero […] used his position of huge influence to perpetuate the tyranny, serial rape, and exploitation organised by West Indian planters, some of whom he counted among his closest friends.”

We’re comfortable denouncing the white supremacists in America, but when it comes to us, we’re much less interested in an awkward confrontation of the past

Afua Hirsch

Speaking to RightsInfo she talks of both “double standards” and an unwillingness to acknowledge the murkier depth of our history. “I’ve been following the events in the US quite closely,” she explains. “I noticed the reaction here has been quite unequivocal [in condemning the white supremicists]. It highlighted to me that there’s quite a double standard. We’re comfortable denouncing the white supremacists in America, but when it comes to our own quite similar history, we’re much less interested in an awkward confrontation of the past.”

A fierce backlash to ‘erasing history’

The former barrister, journalist and author said it was “victors justice”. Image Credit: Afua Hirsch

Perhaps expectedly though, the piece has drawn criticism from both politicians and the public. Conservative MEP Daniel Hannan slammed the idea as “competitive virtue signaling,” while former UKIP leader Nigel Farage said the writer “really hates Britain”. It’s also been the subject of screaming headlines from the likes of the Daily Mail and the Daily Express, while thousands took to Twitter to protest.

Now, it seems, #NelsonMustFall. This is where competitive virtue signalling leads. https://t.co/QQJ3zMkJZE

— Daniel Hannan (@DanielJHannan) August 22, 2017

However, Afua insists she’s “not so interested in toppling statues, but in providing balance and context.” “I think it’s a classic case of victors justice,” she continues. “We won the war, we’re on the right side of history and therefore we don’t need to ask any difficult questions. This is not about erasing history, it’s actually the opposite. Acknowledging history in its fullness and not continuing this one side propaganda.”

A lack of balance, conflict, and interest?

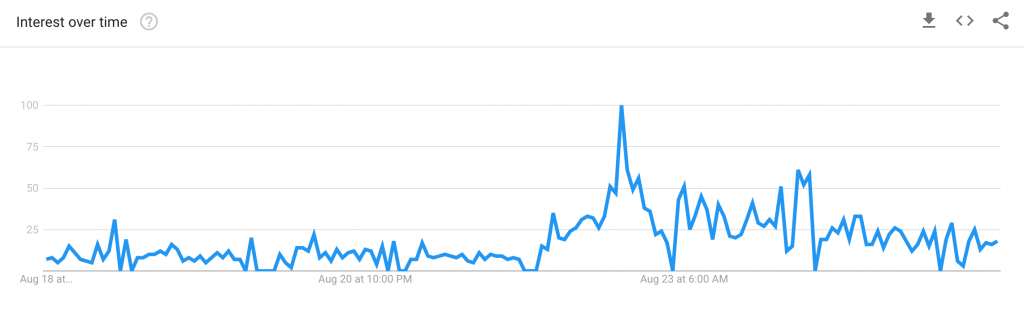

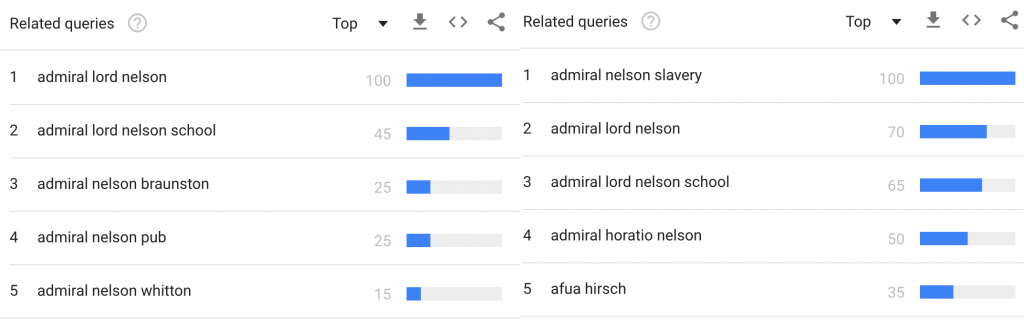

Image Credit: Google Trends

Furious headlines aside there is a more nuanced debate to be had. Jerry White, a historian who focusses on London, argues to RightsInfo that “all are are heroes flawed” if looked at them in the light of modern values. “There are enormous dangers in trying to wipe out the past by forgetting about it,” he adds, referencing a campaign in the Second World War to rename German street names and the destruction of culture by ISIS. “What’s next, rewriting history books? Where do we stop? It would be cultural vandalism. But there’s a great room for dialogue here.”

For Afua though, it’s a question of where this fuller context of history comes from. “What are you doing to provide the full context? We’ve had these statues for centuries, decades and haven’t done anything. Where are the explanations in schools? We’re just continuing to venerate them without any context.”

Image Credit: Google Trends

But do people even know anything about Lord Nelson? Apparently not, according to a Telegraph piece in 2005, which found that school children thought the statue was actually of Nelson Mandela. Similarly, data from Google Trends shows searches tripled on August 22 – the day the article was published. More interesting though, is what people are searching. In the last seven days Google records plenty of searches surrounding Nelson’s links to slavery, in fact, it was the top search. Over the past year though, it doesn’t even rank in the top five. Unlike a school and a pub.

More commemoration, not less

Image Credit: RedCoat / Wikimedia

Despite the furor though, it seems unlikely the monument will ever be taken down. So, what other solutions could there be to addressing Britain’s past? “As a historian, I always think the public are misinformed about a great deal,” adds Jerry. “There are other ways of handling this though.”

“Rather than demolish monuments, which seems to be a destructive and dangerous course of history generally, we should have more. We should commemorate the other side. It’s astonishing and scandalous that there is no monument to the victims of slavery in London. More can be said about the context in which naval wars were waged. But I think the way to do that is to have more commemoration, not less.”

Whatever side of the debate you’re on, it’s hard to disagree that it’s finally started to get us talking about our own past, something which is vital to safeguard our rights in the future.