We all know the story of the First World War Christmas truce. On Christmas Day 1914, the violence on the Western Front came to a halt as British and German soldiers defied officers to play a game of footie.

Ever since, the truce has been used as an example of the unifying role of sport – its ability to foster peace in the place of conflict. In recognition of this, in 2013 the UN designated 6 April the ‘International Day of Sport for Development and Peace’.

Here are five ways that sport in the UK has furthered human rights.

Healing the Wounds of Conflict

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Image: Wikimedia Commons

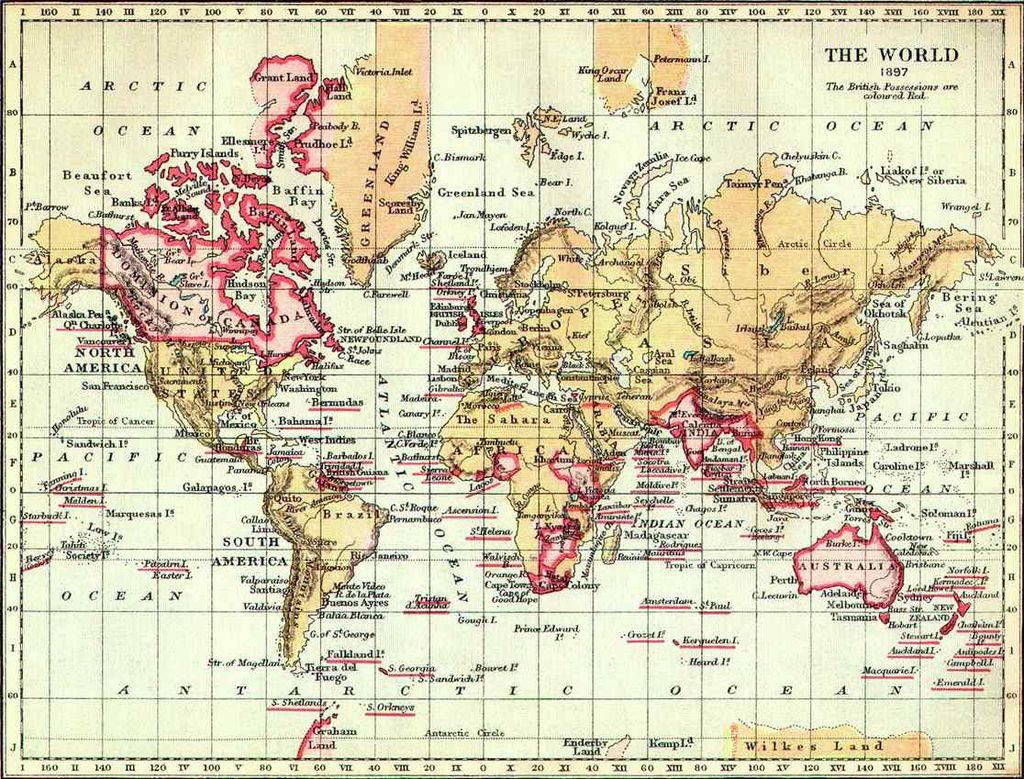

Sport played a controversial role in the British Empire, which at its height accounted for 25% of the world’s total land surface. On the one hand, sport was a tool to impose and maintain English values at the expense of native culture. On the other hand, it united the colonialists and the colonised.

In Britain, sport also helped to shape public opinion. As calls for decolonisation intensified, sporting competitions placed colonies on a equal footing, challenging the perception that they were ‘lesser lands’ in which natives couldn’t expect to enjoy the same human rights as in imperial Britain.

This is particularly true of cricket. Now an integral part of India’s national identity, it has been labelled a form of ‘affirmative action’ for race equality.

The Collapse of South Africa’s Apartheid

Basil D’Oliveira was a South African cricketer of mixed race who grew up under the apartheid government that oppressed all non-white citizens. Knowing that he would never have the opportunity to play for the national side, he migrated to England.

Basil D’Oliveira was a South African cricketer of mixed race who grew up under the apartheid government that oppressed all non-white citizens. Knowing that he would never have the opportunity to play for the national side, he migrated to England.

In 1968, on account of his talent, D’Oliveira was chosen to play for the England national team ahead of its sporting tour of South Africa. His selection was challenged by the South African authorities, who demanded that D’Oliveira be dropped.

England’s subsequent refusal, which led to the cancellation of the 1968 tour, sparked the beginning of a series of international boycotts against South Africa, both in cricket and other sports. These pushed South Africa into sporting isolation, which raised awareness of the human rights violations occurring in the nation and eventually became the ‘Achilles’ heel of the apartheid government’.

Bridging Divisions in Northern Ireland

Sport, particularly football, was once a symbol of Irish sectarian violence. In Scotland, which was a hub for Irish immigrants in the early 20th century, a conflict developed between pro-Catholic team Celtic and the Protestant team Rangers, who for decades refused to sign Catholic players.

Sport, particularly football, was once a symbol of Irish sectarian violence. In Scotland, which was a hub for Irish immigrants in the early 20th century, a conflict developed between pro-Catholic team Celtic and the Protestant team Rangers, who for decades refused to sign Catholic players.

Now, sport in Northern Ireland is being used to bridge differences between these two communities. Organisations like PeacePlayers International, who ‘twin up’ local Protestant and Catholic primary schools and run sporting leagues in Belfast, report a real improvement in tolerance among people who interact through sport.

The appointment of a locally-born Catholic, Michael O’Neill, as the boss of the traditionally Unionist Northern Ireland football team has also gone some way towards unifying the country.

An Alternative to Youth Violence?

Every year, there are gang-related killings in inner cities throughout the UK – and every unlawful killing breaches the human right to life, which is protected by Article 2 of the Convention on Human Rights.

Every year, there are gang-related killings in inner cities throughout the UK – and every unlawful killing breaches the human right to life, which is protected by Article 2 of the Convention on Human Rights.

Recognising the power of sport to divert children away from gang culture, the Metropolitan Police have invested in a range of sporting programmes. These include initiatives such as KICKZ, a football scheme supported by Premier League clubs that encourages ‘hard-to-reach’ young people to swap knives for goal posts.

Research compiled by Laureus Sport for Good Foundation shows that following the introduction of KICKZ, youth violence within a one-mile radius of a North London park dropped by about 68 percent from 2005 to 2009.

Equal Access to Sport

The International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights sets out a duty to ensure that people can participate in cultural life, including sport.

The International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights sets out a duty to ensure that people can participate in cultural life, including sport.

Article 14 of the Convention on Human Rights prohibits discrimination on grounds such as gender and disability. This means, for example, that a woman should not be denied the right to play football because of her gender.

However, there are still distinct inequalities when it comes to participation in, and broadcast coverage of, sport. There have been several campaigns to counter this, for example, Women In Sport’s successful ‘This Girl Can’ campaign. And thanks to London’s Paralympic Games, an additional 222,000 disabled people living in the UK now play sport than when London won its bid in 2005.