The International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition honours the men and women sold into slavery, and those who fought for their freedom in the pursuit of the human rights we still value today. But it isn’t just a historical day – slavery resonates in modern Britain, argues Charlie Duffield.

Commemorated on August 23 every year, it is fair to say it’s a date steeped in history.

It follows the night in 1791 when the successful slave uprising in the French colony of Saint Domingue (now known as Haiti) led to the country’s freedom from colonial rule, and set a precedent for the abolishment of the transatlantic slave trade.

The trans-Atlantic slave trade

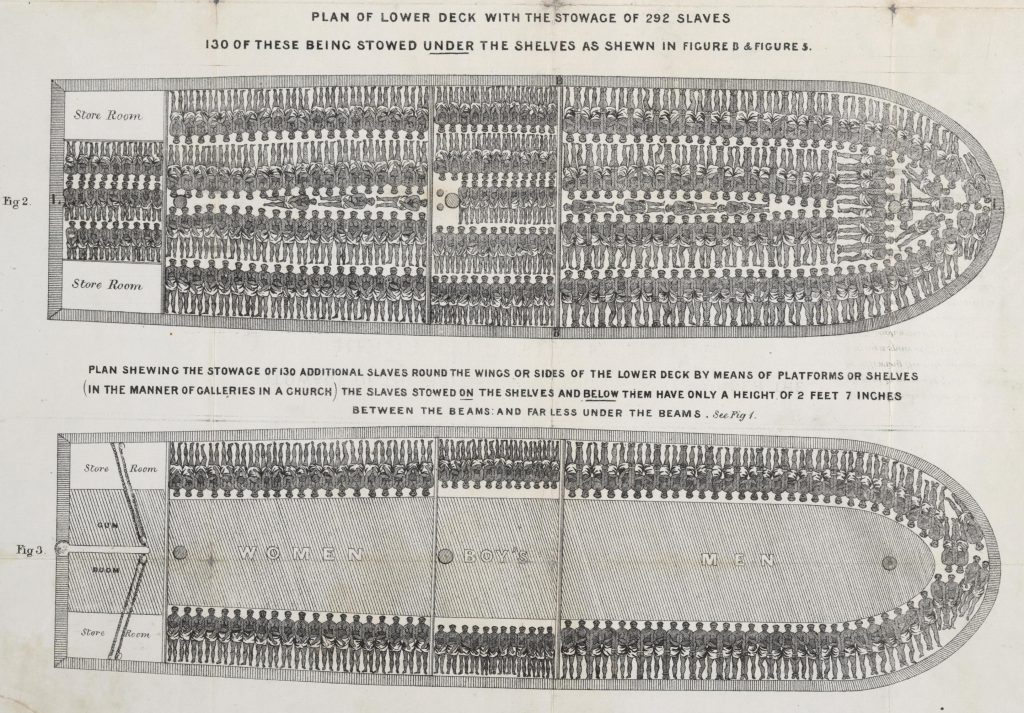

A British slave ship in 1788. Image Credit: Wikimedia

According to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, it’s estimated that between 1525 and 1866 12.5 million Africans were shipped to the New World – to North and South America, and the Caribbean.

Whilst the slave trade reached its peak during the 1780s, approximately a quarter of all enslaved Africans were transported across the Atlantic after 1807.

The conditions on board these slave ships were appalling, and it’s estimated that 12.5 per cent of slaves – 1.5 million people – died before arriving in the Americas.

Abolition was a long and difficult process.

On 25 March 1807, Britain passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, making it illegal to participate in the slave trade within British colonies. The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 technically gave all slaves in British colonies their freedom. It wasn’t until 1885, at the Berlin Conference, that European powers committed to ending African slavery. However, these acts did not completely end the practice.

It goes without saying that slavery is a complete and utter violation of our human rights

Charlie Duffield

In the United States of America, slavery was not officially abolished until 1865, with the introduction of the 13th amendment. Illegal slaving still persisted, with the last known slave ship landing in Cuba in 1867. Brazil was the last country to emancipate slaves in 1888.

It goes without saying that slavery is a complete and utter violation of our human rights.

When the Human Rights Convention was ratified in 1953, Article 4 stated that no one shall be held in slavery or servitude. Also in 1948, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, stating that: “No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.”

A lasting legacy of slavery

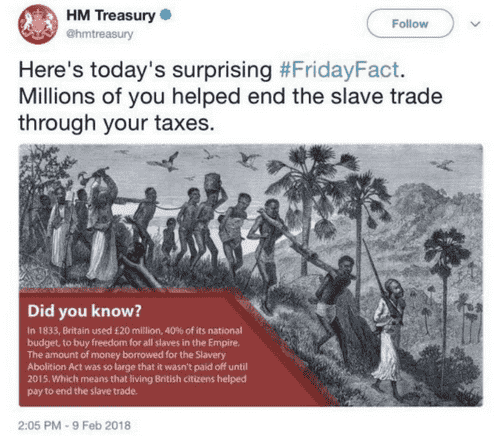

The tweet was hastily deleted. Image Credit: Twitter

The history and recollection of slavery and its abolition is contentious.

In February 2018, the Her Majesty’s Treasury claimed that the slave trade was ended thanks to UK taxpayers.

In a tweet, which has now been deleted, it was claimed that in 1833, Britain used £20 million – 40 per cent of its national budget – to buy freedom from all slaves in the Empire. They concluded by saying the sum was only fully repaid in 2015 – meaning many of us living now will have contributed.

Actually, that £20 million was used to compensate 46,000 slave owners for their loss of ‘property’.

The extent of slave ownership in British society

Image Credit: Cassoway Colorizations / Flickr and UK in Latvia / Flickr

The Slave Compensation Commission, highlights how widespread slave ownership was in British society. Families of prominent figures such as George Orwell and David Cameron are amongst those who owned slaves. University College London (UCL) has collated this data into a website Legacies of British Slave Ownership.

In response to the publication of such information, many institutions are questioning their historic links to the slave trade. For example earlier this year Bristol’s largest concert hall, Colston Hall, announced that the building would be renamed, so as not to be associated with the slave-trader Edward Colston.

Writing in the Bristol Post, Louise Mitchell, chief executive of the Bristol Music Trust, commented: “The name Colston does not reflect the trust’s values as a progressive, forward thinking and open arts organisation.”

However, even this isn’t a clear consensus, with Conservative Councillor Richard Eddy of Bristol City Council, expressing concern to EachOther at the modification of historic landmarks.

“We shouldn’t try to sanitise history to reflect our 21st century sensitivities,” he added. “Good, bad or indifferent actions were done in every age. The study of history is vital to ensure we do not repeat the errors of the past, or allow evil men to triumph. If certain values or individuals were admired in the past, they should be maintained to preserve an authentic view of the past.”

Wider divisions over our past – and future

Image Credit: Neil Howard / Flickr

It’s an issue that extends beyond Bristol, with debate also raging after broadcaster Afua Hirsch suggested toppling Nelson’s Column due to his links with the slave trade.

“The contention over colonial statues and landmarks reflects wider divisions over Britain’s past, and over our future,” explains Nick Draper the director of the new Centre for the Study of Legacies of British Slave Ownership at UCL.

“Those divisions cannot be easily healed, but if we keep the historical evidence clearly in sight, we have a better shot at reconciling competing views,” he tells EachOther.

“Let’s establish the facts in each case; then we can debate their implications; and then we can appropriately amend or adjust the ways in which we remember, or memorialise, our shared pasts.”

The contention over colonial statues and landmarks reflects wider divisions over Britain’s past, and over our future.

Nick Draper

UCL Collections Curator Subhadra Das has explored the issue in great depth through her exhibition Bricks + Mortals. The collection and podcast, which is a history of eugenics told through buildings, is very close to home.

UCL’s Galton Lecture Theatre, for example, is named after the renowned colonialist and racist scientist Francis Galton, yet her outlook is hopeful.

“I’m optimistic that by telling these stories, and by acknowledging and re-addressing these histories, we’re in a position to change the structures of society which perpetuate racism,” she explains to EachOther.

‘Statues are unambiguously positive statements by society’

UCL Collections Curator Subhadra Das believes a conversation around slavery can help address structural racism in Britain today

However, for Dr Das, there is a clear distinction between differing types of monuments. “Statues are unambiguously positive statements by society. That is someone who is literally put on a pedestal, so we can look up to them.

“Having a statue of Edward Colston in Bristol, means that we should look up to someone who is a slave owner and made his fortune based on the enslavement of African people. A lot of people would argue that if you pull down a statue, you’re reinforcing just how bad a person they were,” she adds.

That is someone who is literally put on a pedestal, so we can look up to them.

Dr Subhadra Das

\

“Artistic interventions – such as when the statue of Winston Churchill was defaced with a turf Mohawk – stimulate a social dialogue to think critically about our histories. With building names, there’s more room for nuanced discussion, but the statues can just come down.”

It would seem that Britain is a long way from acknowledging their colonial past and the modern ramifications inflicted from such an enormous and barbaric system of human exploitation. Whilst opinions differ regarding the decolonisation of public monuments, Slavery Remembrance Day emphasises the urgency and great need to start the conversation at least.