From April to July in 1994, up to 1,000,000 people in Rwanda were murdered by members of the Hutu ethnic majority.

The humanitarian disaster followed a complex history of colonialism, discrimination, and power shifts. One of the worst genocides in living memory, and little more than 20 years ago, it is a tragic reminder of how vital human rights are.

Rwanda: Some History

A reconstruction of the King’s palace in Rwanda. Image Credit: Amakuru / Wikimedia

A reconstruction of the King’s palace in Rwanda. Image Credit: Amakuru / Wikimedia

Before its colonial rule (by Germany from 1897, and Belgium from 1917), Rwanda was a complex and advanced monarchy. The monarch ruled the country through official representatives drawn from the Tutsi nobility.

At that time Rwanda had some 18 clans defined broadly along family and marriage lines. The terms “Hutu” and “Tutsi” were used, but they referred to individuals, not groups. Hutu and Tutsi people were defined by lineage, not ethnicity. One could also move from being a Hutu to a Tutsi, or vice versa, through marriage.

The colonial authorities (first Germany, then Belgium) relied on an elite essentially comprised of people identifying as Tutsi. According to Rwanda expert Dr. DesForges, this choice was born of racial or even racist considerations. According to her account:

In the minds of the colonizers, the Tutsi looked more like them, because of their height and colour, and were, therefore, more intelligent and better equipped to govern.

In the early 1930s, Belgian authorities divided the Rwandan population into three groups: Hutu (84%), Tutsi (15%), Twa (1%). Every Rwandan had to carry an identity card stating his or her identity. This requirement was maintained, even after Rwanda’s independence, until the tragic events in 1994.

The Move to Independence

Juvénal Habyarimana became President of the independent state in 1973 Image Credit: Public Domain

Juvénal Habyarimana became President of the independent state in 1973 Image Credit: Public Domain

In the late 1940s, Belgium shifted its allegiance from the Tutsi minority to the Hutu majority, after the Tutsis sought Rwanda’s independence (realising their privileged status and potential for political leadership). Belgium then granted more opportunities to the Hutu to acquire education and hold government positions. This angered the Tutsis, who then fought harder for Rwanda’s independence. At the UN’s insistence, Belgium organised elections on the basis of universal suffrage.

Since voters voted along ethnic lines, the Hutus obtained an overwhelming majority in Rwanda’s first elections. The Hutus became aware of their political power, and the Tutsis of the demise of their supremacy. Four political parties emerged, with MDR Parmehutu (the Hutu grassroots movement), at the helm. They remained in power when Rwanda declared independence in 1962.

Cycles of Violence & Discrimination

A father searches for his lost child. Image Credit: The Red Cross / Flickr

A father searches for his lost child. Image Credit: The Red Cross / Flickr

Many Tutsis left the country from the early 1960s onwards, with the Hutu majority government in power. Some Tutsi exiles launched incursions from neighbouring countries. They came to be known inside Rwanda as “Inyenzi”, meaning cockroach. Each attack was followed by reprisals against the Tutsis within Rwanda, which, in 1963 is said to have caused tens of thousands of Tutsi deaths. This led to the exile of more Tutsis, with the Hutu-led government then distributing the former Tutsi land to the Hutu. The government also redistributed government posts in favour of the Hutu.

Following dissent within the political system, President Habyarimana instituted a one-party State in 1975. At first, the Tutsi were hopeful as he did not pursue clearly anti-Tutsi policies. However, this changed with time, and a policy of systemic discrimination against the Tutsi was pursued with respect to government positions and education. Habyarimana’s power decreased when he instituted discriminatory policies even amongst the Hutu themselves (favouring Hutu from his own native region in the north-west).

In 1990, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF – formed of Tutsi exiles) launched an attack from Uganda, which served as a pretext for the arrest for thousands of opposition members in Rwanda believed to support the RPF.

Genocide

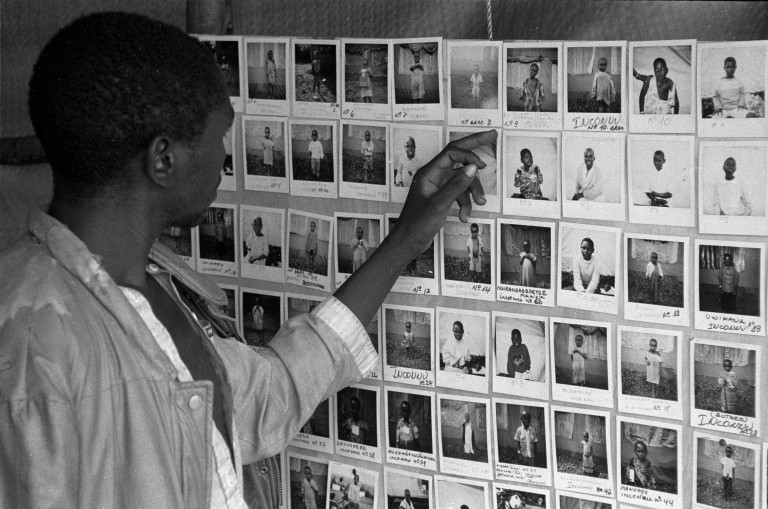

Images of Genocide Victims. Image Credit: Adam Jones / Wikimedia

Images of Genocide Victims. Image Credit: Adam Jones / Wikimedia

The Tutsi exiles in RPF formed a military wing (the RPA) with the objective of returning to Rwanda. Violence between the Hutu government and the RPF ensued. President Habyarimana was on the brink of signing a peace accord when, on 6 April 1994, an aircraft returning him from the peace according meeting crashed, killing all on board.

This triggered the Presidential Guard and militia to start killing Tutsi and Hutu known to be in favour of the Peace Accords and power-sharing between Tutsi and Hutu. The president of the Supreme Court and many members of parties in the coalition government were killed. This power vacuum paved the way for the establishment of the self-proclaimed Hutu-power interim government. Belgian and UN forces withdrew from Rwanda.

On April 12, 1994, public authorities on the radio stated that “we need to unite against the enemy, the only enemy…the enemy who wants to reinstate the former feudal monarchy”. A killing campaign ensued, with primarily Tutsi people as its target. It is said that thousands of people, sometimes encouraged by local administrative officials on the promise of safety, were directed to churches, schools, and hospitals. However, this was a trap intended to lead to the rapid extermination of a large number of people.

The Aftermath

A commemoration for the lives lost in the genocide. Image Credit: UNAMID / Flickr

A commemoration for the lives lost in the genocide. Image Credit: UNAMID / Flickr

The RPF defeated the government’s forces on July 4, 1994, leading many Hutus to leave the country, fearing reprisals. Rwanda’s infrastructure and economy suffered greatly through the genocide. The international community was harshly criticised for not doing more. Local and international courts were set up to try to bring the perpetrators of the genocide to justice, with many being convicted and imprisoned.

Although Rwanda has shown many signs of healing, it still bears heavy scars from the past violence culminating in the 1994 genocide.

You can read more on the Rwandan Genocide here.

This piece is part of our #FightHateWithRights series and made possible by you through our crowd funder. The documentary, which will be launched on November 16, tells the story of one of the survivors of the Rwandan genocide.