Throughout 2021, EachOther reported on human rights issues across the UK, including those affecting people on account of their characteristics protected under the Equality Act. To usher in the new year, we are highlighting the issues that are particularly affecting five such groups in UK society, looking forward to the opportunities 2022 might afford them and the challenges the year ahead might pose. In this mini-series, we focus on these five of the nine protected characteristics in the Equality Act: race, sex, sexual orientation, disability and religion.

Disabled people endure human rights abuses on a daily basis. This has been exacerbated during the coronavirus pandemic. Institutionalised ableism besets health and social care systems in the UK.

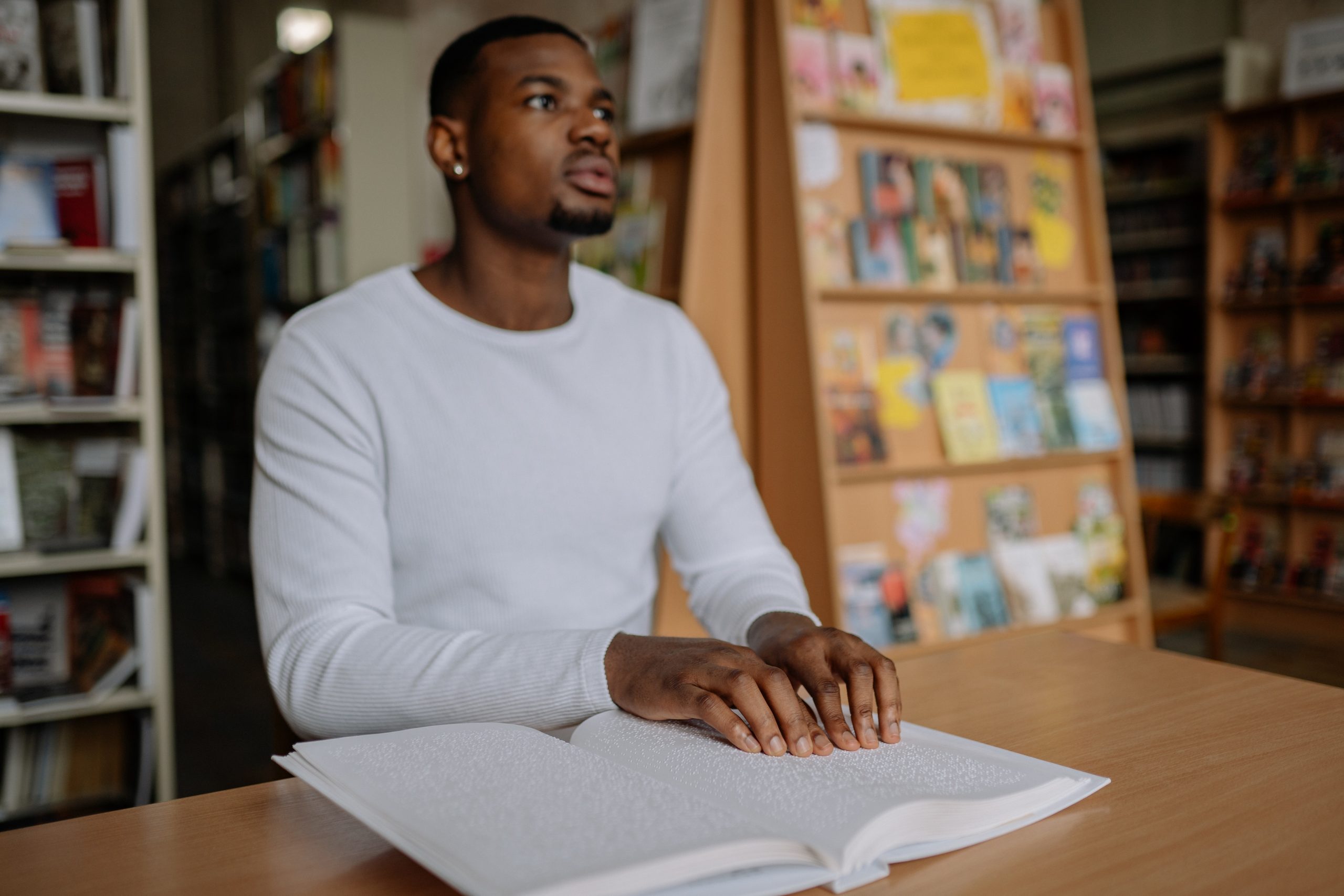

Credit: Yan Krukov / Pexels

The Equality Act defines disability as “a physical or mental condition that has a substantial and long-term impact on a person’s ability to do day-to-day activities”. Long-term is typically considered to be at least 12 months.

“It feels like a lot of things have been happening which are disabling us, in the way that the social model of disability acknowledges,” observed Helen Jones, steering group member for York Disability Rights Forum (YRDF). “Whether it’s reduced access to cities, reduced access to medical services or something else. Barriers that weren’t there previously, or weren’t as acute, are now making our lives more difficult and making people less independent.”

Currently, there are an estimated 14.1 million disabled people in the UK, equating to 19% of working-age adults, 46% of pension-age adults and 8% of children. Despite making up approximately 20% of the UK population, disabled people’s rights have been threatened on a regular basis throughout 2021 and the forecast for 2022 does not necessarily look much brighter.

How were disabled people’s rights impacted in 2021?

Credit: Kampus Productions / Pexels

The years 2020 and 2021 saw a wide range of human rights violations against disabled people, especially in the health and social care sectors. Rights that were breached included freedom from discrimination, freedom from inhumane or degrading treatment and to life itself.

Social care

One of the most significant areas of rights abuses against disabled people was in the provision of social care. In 2019/20, 838,530 adults received publicly funded long-term social care – primarily in their own homes or in care or nursing facilities – and 231,296 episodes of short-term care were provided. Expenditure on adult social care by local authorities increased by £1 billion between 2018/19 and 2019/20 but, in real terms, adjusted for inflation, total expenditure has only increased by £99 million since 2010/11.

Last September, the government resurrected plans to cap care service costs and relax the limits placed on means-testing. While aspects of the plan were welcomed, critics argued that the scheme does not provide any additional funding for care.

At the time ADASS, the Association for Directors of Adult Social Services, demanded “urgent clarification of the plan”.

“This has been billed as a big social care announcement, but beyond the implementation of a cap on individuals’ personal financial contributions and a raising of the lower limit of when people are charged in the future, the additional money is all going to address issues in the health service,” said ADASS president Stephen Chandler. “Unless there is something significant added, very little, if any, of the £36 billion that has been announced is ever likely to make it to adult social care budgets via the NHS.”

The continued disappointment vis-a-vis social care provision is felt by many disabled people struggling to afford appropriate care.

“The social care reforms haven’t helped in any way,” said Ian Wyllie, who has a spinal injury. “Essentially, it makes starting off on a competitive salary impossible because of care costs. If I’ve been financially responsible and saved, or if I’ve got income, then I could be over the cash limit and immediately I’m paying 100% of my care. It’s denying disabled people an effective place in society and it’s denying them the right to participate in society too.”

Under Article 11 of the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, everyone has the right to an adequate standard of living, which includes access to food, clothing housing and a continual improvement of living conditions. Financial barriers to appropriate care are endangering this right for disabled people who may have to sacrifice other essentials to pay for their care.

Throughout the coronavirus pandemic, staff shortages and restrictions have left disabled people struggling without human touch or affection, endangering their wellbeing. During the pandemic, Jennie Williams CEO of Enhance the UK, a charity that provides accessibility training and advocates for changing how disability and sex are viewed, noted a marked increase in people writing into their Love Lounge for support.

“People write saying ‘I’m depressed, I’m lonely, I’ve had no touch’,” explained Williams. “Imagine only ever having touch with someone who puts a rubber glove on before touching you. People are relying on a family member coming in because staff are not allowed to cuddle you. It has a huge impact on people’s mental health.”

Healthcare

Credit: Anas Aldyab / Pexels

The coronavirus pandemic has devastated the disabled community. Disabled people have made up 59% of Covid-related deaths and reports of do not resuscitate orders being placed on disabled people have surfaced multiple times since the pandemic began. The government has also repeatedly failed to include accessible guidelines and press briefings for disabled people.

“People who perceive themselves to be extremely vulnerable have been left without any useful advice and are essentially becoming detained,” said Wyllie. “It will be very difficult to see the scale of this problem because people just disappear from the radar. That’s a major human rights issue because these people are unable to participate in society, they don’t have a right to a family life and they don’t have a right to the same liberties as everyone else around them.”

The pandemic has also affected people’s right to access to healthcare. Waiting times have grown, accessing rehabilitation services has become increasingly difficult and crucial operations have been repeatedly postponed.

“Access to healthcare services has got worse and has made existing health inequalities worse,” said Jones. “Appointments seem to be less available and harder to book, long waits on phone systems, unintuitive online booking forms, receptions are not open to booking appointments face-to-face, which is important for the deaf and hard of hearing communities. This exclusion is amplified because most GPs don’t have a text or email option.”

Employment

Credit: Kampus Production / Pexels

The disability employment gap has remained at 28.4%, which has been relatively static for close to a decade, and disabled people remain half as likely to be employed as non-disabled people and are more likely to live in poverty.

Prevailing misconceptions around disabled people’s ability to work is certainly a driving factor but accessibility to workplaces is also a barrier, particularly following a reduction in remote working as lockdown restrictions eased further last summer.

“Employers are still somewhat more hesitant to take on disabled people who have good scholastic or academic qualifications, simply because they may have to make some adjustments around the physical layout of the office location or business to accommodate the requirements,” explained Peter Lyne, founder of the Mobility and Support Information Service (Masis).

Accessibility

Accessibility for disabled people has remained a significant rights issue throughout 2021, with public transport services neglecting accessible travel. The London Underground system remains largely inaccessible for wheelchair users and train companies have been plagued with reports of disabled passengers encountering ableism when accessing transport.

“In York specifically, our access to the city centre has been reduced,” said Jones. “The City of York Council Executive voted to permanently exclude blue badge holders from driving/parking/being dropped off by taxi in key streets in the city centre. This was following 18 months of temporarily not being allowed this access.”

How were the rights of disabled people protected in 2021?

While it was heavily criticised for several failures, such as omitting food poverty and education provision, the National Disability Strategy saw the government outline its plans to help improve equality for disabled people in the UK.

The strategy pledged to spend £300 million on supporting children with additional educational needs and disabilities. Its authors also outlined plans to increase the number of accessible homes, employ more disabled people in government intelligence agencies and audit mainline railway stations for disabled accessibility.

Next up, the government’s proposals to adjust the social care system contained some potentially positive changes for 2022, but many will not be enacted until 2023 and beyond. For example, the government plans to lift the freeze on minimum income guarantee for home care users and personal expenses allowance for those in a care home, so each will rise with inflation from April 2022. The reforms would require councils to arrange care for self-funding care home residents if they request it, allowing them to pay the same rates authorities pay for care rather than the higher fees often levied on people paying privately for care. The government has also pledged £500 million to support the care sector workforce.

What are the key issues going to be for disability rights in 2022?

Credit: This Is Engineering / Pexels

In 2022, many of the same issues that afflicted disabled people during 2021 remain a threat to their rights, especially with the ongoing pandemic. However, three key areas are likely to be at the forefront: accessible transport; hate crime; and health and social care.

Transport accessibility remains a significant barrier to disabled equality, especially as disabled people are more vulnerable to hate crime on public transport. At Masis, the group aims to focus on improving access to personal transport to protect particularly vulnerable disabled people.

“We know that people within either LGBTQ or disability sectors are at greater risk of being verbally or physically abused, especially if they are increasingly dependent on public transport services,” said Lyne. “Consequently, one of the themes we’ll be addressing in quite a large level of detail will be transportation.”

At YRDF, the group’s members have outlined a need for a concerted effort to improve understanding of people’s varying needs in medical appointments, improved access to such appointments, and an evolved mental health crisis line service that does not assume everyone can use the phone.

“More broadly, the issues around health and care nationally will be most significant and will probably continue to worsen,” said Jones. “The NHS and care system has felt the crush of 10 years of a Conservative government and then the pandemic has really just been the icing on the cake.”

A great deal of progress is yet to be made towards equality for disabled people in the UK. Disabled communities, disability campaigners and their allies will be busy once again in 2022.