Victims of crimes, including rape, will be asked to sign a consent form to hand their mobile phones over to the police, or risk their cases being thrown out.

Investigating officers will use the forms to gain access to personal information, including emails, messages and photographs, in new guidelines being rolled out across forces in England and Wales.

The form reads:

If you refuse permission for the police to investigate, or for the prosecution to disclose material which would enable the defendant to have a fair trial then it may not be possible for the investigation or prosecution to continue.

Police and prosecutors argue that the forms are an attempt to get around the law, which currently says that complainants and witnesses cannot be forced to disclose any private information held on devices.

The consent forms can be used for complainants in any criminal investigation. However, they are most likely to be used in rape and sexual assault cases, in which the suspects are often known to the complainants.

What Is Being Said About The New Policy?

Max Hill, the Director of Public Prosecutions, said that the forms would only be used where access to the personal information of victims forms a “reasonable line of enquiry”. Only relevant material from devices, he adds, will go before the courts.

Even so, a number of concerns have been raised about the potential rights violations that could occur under the new policy.

Rachel Almeida from Victim Support said: “We know that rape and sexual assault is already highly under-reported and unfortunately this news could further deter victims from coming forward to access the justice and support they deserve.”

Big Brother Watch, a civil liberties charity, told the BBC that victims should not have to “choose between their privacy and justice”.

We seem to be going back to the bad old days when victims of rape are being treated as suspects.

Director of the Centre for Women’s Justice, Harriet Wistrich

“The CPS is insisting on digital strip searches of victims that are unnecessary and violate their rights,” the organisation added.

The Centre for Women’s Justice (CWJ) is already planning a legal challenge to the new rules. At least two women are launching complaints into the already standard practice of being asked to hand over personal information, or risk their cases being dropped entirely.

Image credit: Harriet Wistrick, director of CWJ/ Wikimedia

“Most complainants fully understand why disclosure of communications with the defendant is fair and reasonable, but what is not clear is why their past history (including any past sexual history) should be up for grabs,” Harriet Wistrich, the CWJ’s director, said.

“We seem to be going back to the bad old days when victims of rape are being treated as suspects.”

Meanwhile, the Metropolitan Police released a statement on the “awkward” and “inconvenient” nature of the practice.

“People who have been victimised and subjected to serious sexual assaults, for example, that’s an awful thing to happen to them and you don’t wish to make it worse by making their lives really difficult,” it read.

“But to pursue the offender, the way the law is constructed, we do have these obligations, so we have to find a way of getting that information with a) as much consent as we can, which is informative and b) with the minimum of disruption and irritation and embarrassment to the person whose phone it is that we’re dealing with.”

What Are The Rights Of A Victim?

Victims of crimes have the right to expect a certain standard of service from the criminal justice system. In the UK, these rights are outlined in the Victim’s Code.

Key rights under the code include:

- To be kept informed about the progress of your case by the police

- To hear when a suspect is arrested, charged, bailed or sentenced

- To be able to apply for extra help when giving evidence in court if you are vulnerable, intimidated, or a child or young person

- To be able to apply for compensation

- To make a Victim Personal Statement to explain the impact of the crime, and to have it read out in court, with the permission of the court

- To be told when an offender will be released, if that offender has been sentenced to a year or more in prison for a violent or sexual offence

- To be given information about taking part in restorative justice schemes

- To be referred to victims’ support services

- To seek a review of a decision not to prosecute

Victims are also entitled to a certain level of privacy. Police forces should ask permission from the complainant or their family if they publish any details of the crime to the media in order to gather more information about a case.

In sexual assault and rape cases, it is illegal for the name of the complainant or a photograph of them to be published anywhere.

Those who feel their rights are not being met can complain to any criminal justice agency, from their local police force to the Crown Prosecution Service.

How About An Individual’s Human Right To A Private Life?

Article 8 of the Human Rights Act outlines everyone’s right to privacy, and protects individuals from intrusion into their personal lives.

This includes unnecessary surveillance from the state, or the unfounded use of personal data.

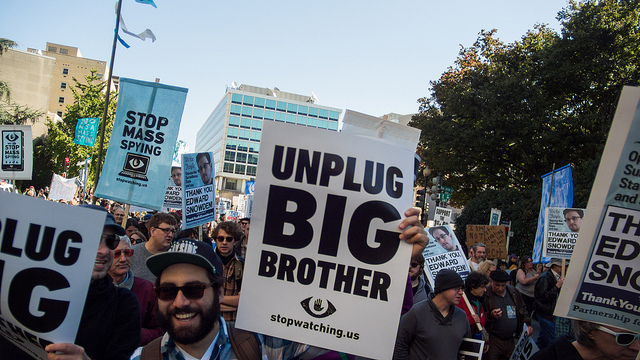

Image credit: Surveillance protest/Flickr

Someone’s right to privacy can only be interfered with when it is “necessary to do so in a democratic society” for the protection of life, the safety of others, protecting national security or preventing crime.

Even so, any interference into this right must be deemed “proportionate”, and information is to be used only when absolutely necessary to achieve one of these aims.

For more information on what to expect from the police if you have been a victim of crime, see the government website here.