Britain’s police still inflict “unconscious bias” on ethnic minority communities, the leader of Britain’s police chiefs has said in an interview to mark the 20th anniversary of the Macpherson Report into the murder of Stephen Lawrence.

Sara Thornton, Chair of the National Police Chiefs’ Council, said she believed the law should be changed to allow positive discrimination in favour of minority ethnic recruits.

Otherwise, police forces will be disproportionately white for decades to come, Thornton warned.

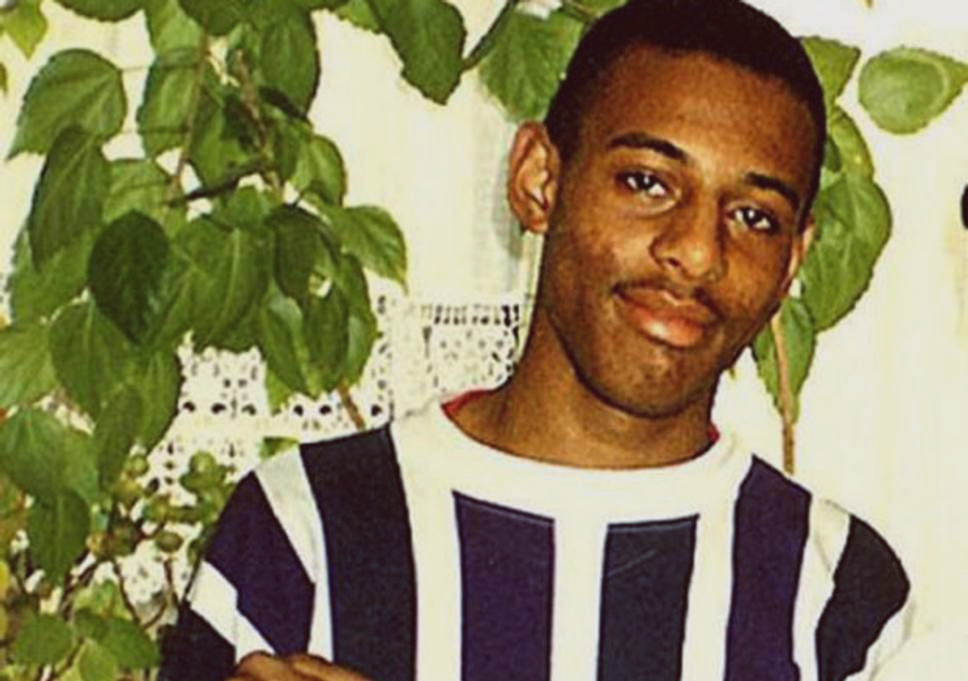

The 1993 murder of Lawrence, aged 18, at a bus stop in south London and the subsequent failing by the Metropolitan police to properly investigate his killing, made it impossible for policymakers and the general public to ignore what would become known as the ‘institutional racism’ within Britain’s police force.

What Did The Macpherson Report Change?

Image via Telegraph

After the Macpherson report was released in 1999, the government set targets for every force to have the same proportion of minority ethnic officers in their ranks as the communities they served. They were given a decade to achieve this.

However today just 6.6% of officers are from ethnic minority backgrounds, compared to 14.9% of the overall population.

Among forces, the Met Police are statistically the worst, with just 14% of officers from ethnic minorities, compared to 43% of the city’s population.

Thornton, who is approaching retirement after 33 years working for the police, said she believes positive discrimination – the process of actively choosing to hire candidates from under-represented groups over other applicants – is the only way for the force to see real change.

At the current rate of progress, if nothing changes, researchers have predicted it will take at least 60 years, if not 100, for the police force to meet the 1999 target.

What Is ‘Positive Discrimination’ And Why Isn’t It Allowed?

Under the Equality Act 2010, it is illegal to discriminate against someone on the basis of nine protected characteristics: age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation.

It is also generally against the law to use positive discrimination – also known as positive action or affirmative action – to recruit people with one or more of these characteristics over other better-qualified candidates, even when it is to try and address a pre-existing disparity within the organisation.

Official guidance for employers states “You must not have a policy of automatically treating job applicants who share a protected characteristic more favourably in recruitment and promotion. This means you must always consider the abilities, merits, and qualifications of all of the candidates in each recruitment or promotion exercise.”

You must not have a policy of automatically treating job applicants who share a protected characteristic more favourably in recruitment and promotion.

Under the Act, positive discrimination in recruitment is usually only allowed in tie-breaker situations. This is based on the argument that merit is the most important characteristic of a person, and should be the primary criteria for choosing who to hire.

For example, if one man and one woman apply for a senior management position in a company where all the current managers are men, the recruiter is only allowed to take gender into account when making a decision if the two candidates are otherwise equally suitable for the role.

Advocates of positive discrimination argue that this isn’t actually fair because structural inequalities like racism, sexism, homophobia and ableism that exist in society mean people with protected characteristics don’t start from the same place as, or compete on a level playing field to, others with non-minority status. Positive discrimination is therefore seen as compensating for an unfair and unearned advantage that some people may start with.

Is Britain’s Police Force Racist?

Image via Flickr

The Met Police had long been accused of being racist, but the Macpherson report made it far harder to dismiss this criticism.

Published in February 1999, the inquiry defined institutional racism as the “collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture, or ethnic origin” through “unwitting” prejudice or ignorance that influences processes.

Tackling this was made a priority, but evidence shows that twenty years on officers still disproportionately target black people with stop and search.

Ethnic minority communities have also been found to be policed more violently. Statistics released for the first time in December 2018 also showed that police use force disproportionately against black people in England and Wales. The figures, released by the Home Office, showed that 12% of incidents recorded by police as involving the use of force were against black people, who make up only 3.3 per cent of the population.

This is not just bad luck. Asian families ask whether their sons and daughters are going to be discriminated against before they even think about joining … race discrimination in policing is known to our communities.

– Tola Munro

Tola Munro, president of the National Black Police Association, told the Guardian a radical change on race discrimination is needed. “Race discrimination, disparities and a lack of representation throughout the service show that the culture of policing has not changed for black, Asian and mixed-race people,” he said.

Munro said one of the reasons the police force has trouble recruiting minority ethnic officers is that communities know the force is prejudiced against them. “This is not just bad luck,” he said. “Asian families ask whether their sons and daughters are going to be discriminated against before they even think about joining … race discrimination in policing is known to our communities.”