Campaigners have lost a landmark legal battle against the UK government’s handling of raising the state pension age for women born in the 1950s. The ruling suggests an enduring disregard for women growing older in a society where gender-based ageism is entrenched, writes academic Kathleen Riach.

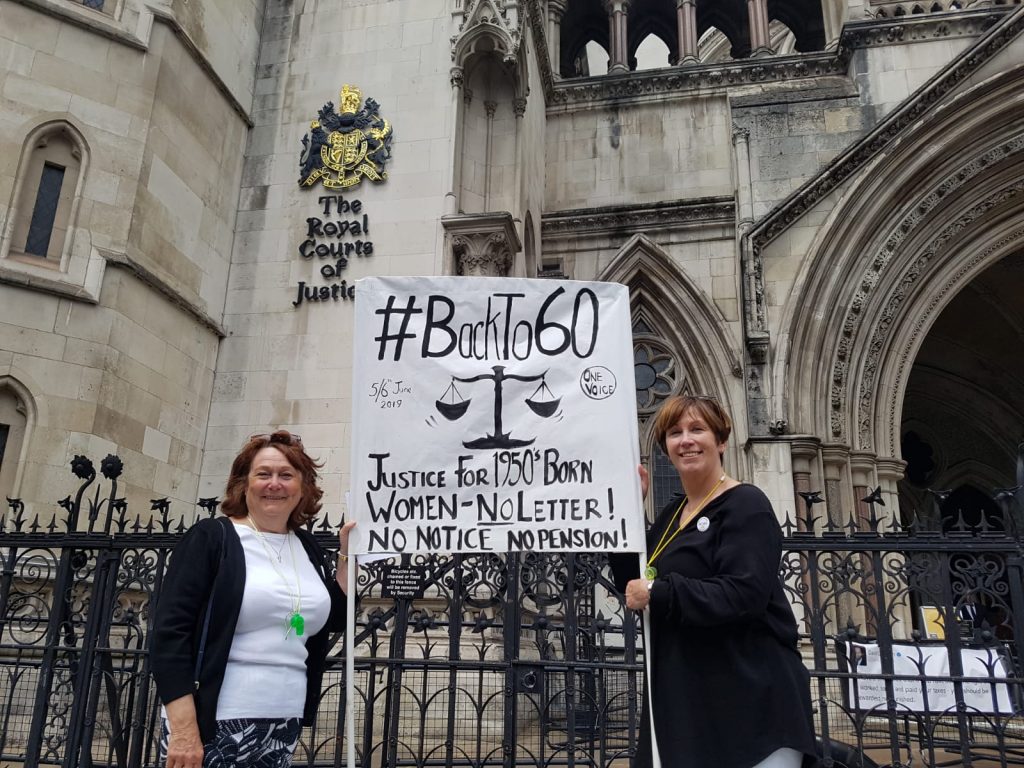

Julie Delve, 61, and Karen Glynn, 63, supported by grassroots campaign Backto60, argued that the decision to raise the pension age from 60 to 65 discriminated against women born in the 1950s, and there was a lack of communication and insufficient notice given. However, the judges disagreed.

The judicial review was a landmark for a number of reasons. It is one of the few times a government in Europe has been taken to court for welfare policies that discriminate on account of age. It was also one of the few cases to have appeared in UK courts where the intersectional issues of age and gender discrimination were raised – that is, the idea that gender and age inequality come together to create discrimination that is more than the sum of the parts of gender and age in isolation.

The decision in favour of the government not only has a significant material impact on the 3.8 million women whose pension eligibility was affected, it also suggests an enduring disregard for one of the most vulnerable groups in today’s society – older women.

Disadvantage And Discrimination

Credit: Aaron Walawalkar / EachOther

The financial insecurity of older women is a concern across the Western world. A report by the Australian Human Rights Commission showed they were the fastest-growing cohort experiencing homelessness. The greater likelihood of older women living alone also increases their risk of financial abuse.

Women retire with smaller pension pots than men, and a larger proportion of their pension income is derived from government pensions, rather than occupational pension schemes.

The disadvantage women face throughout their working lives is due to several factors coming together. Reductions to the gender pay gap continue at a glacial pace. The “motherhood penalty”, aside from maternity leave, means a significant drop in earning potential over the rest of women’s working lives. Motherhood results in full-time working women earning around 7 per cent less than women of the same age with the same education and occupation status.

Studies from the US also show mothers are rated lower than non-mothers in terms of perceived competency, and are less likely to be recommended for jobs – both of which harm their earnings potential. And women are also more likely to take on the majority of caring responsibilities for elderly parents and relatives. Pension pots do not take into account all of this unpaid labour.

There are more indirect dimensions that limit women’s earning potential but are not traditionally associated with financial insecurity in older age. For example, misdiagnosis and late diagnosis of women’s health conditions, such as menopause and endometriosis, can reduce women’s ability to maintain full participation in the workforce and affect pension and savings contributions. Stigma and gender-based stereotypes associated with women’s bodies more generally affects their career opportunities too.

Financial Aftershocks

Image Credit: Unsplash.

Economic disadvantage also accumulates through life experiences that disproportionately hurt women’s economic situations. These can be understood as financial aftershocks. Here the event may not directly be associated with financial insecurity, but the long-term outcome is.

When it comes to divorce and separation, for example, guidelines are in place to ensure a fair and equitable split of private pensions. But a report by the insurers Scottish Widows in 2017 highlighted that discussion of pension distribution is often overlooked during divorce proceedings. This tends to affect women disproportionately, as men are more likely to have larger amounts in occupational pension schemes.

The average age of divorce for women in England and Wales is 44 years – and men in opposite-sex couples continue to be the main financial contributors to the household. This means that a number of women find themselves navigating the often huge economic ramifications of this kind of unexpected event. The sudden change in legislation and eligibility has compounded their level of insecurity.

Elsewhere, a small but valuable study by the charity Women’s Aid also showed that domestic abuse has significant consequences. Of the 72 women interviewed, 18 per cent said their partner prevented them from having paid employment and 40.3 per cent of all respondents felt that their long-term employment prospects and earnings are worse because of the abuse.

All of these factors are vital to consider if we are to recognise and appreciate that women’s economic position in later life is a complex story. Gendered experiences coalesce with structural patterns, which makes the ruling extremely shortsighted.

The Fight Continues

Credit: Aaron Walawalkar /EachOther

This judgement may only be the start of the Backto60 campaign as they seek justice. There are alternative legal routes campaigners may choose to take, and a motion to enact special measures to provide support for the women caught in this demographic pensions trap has now been signed by more than 220 MPs.

Campaigners may choose to align with other groups such as WASPI (Women Against State Pension Inequality). WASPI has so far taken a more moderate stance, and is predominantly concerned with bridging pension arrangements or compensation as part of how equalisation is implemented.

The ruling is part of a bigger story about social and economic patterns of cumulative disadvantage. Yet current messages continue to imply women should simply “try harder” (or worse, should have tried harder) to secure their own financial futures and that making the pension age the same for women and men should be viewed as equality in action.

This is salt in the wound for women who are growing older in a society where gender-based ageism is entrenched in how we live and work.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Want to know more? Why not read: