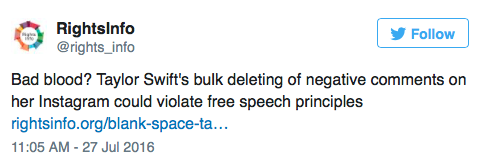

On Wednesday I posted a Tweet. It said this:

The aim was to promote a RightsInfo article written the day before about the free speech implications of Instagram’s reported new app that allows celebrities – like Taylor – to bulk delete people’s comments on their accounts. But the Tweet prompted a backlash I had not seen before. People’s comments varied from the genuinely concerned: “@RightsInfo You can delete comments on your own page surely?” to the downright baffling: “Hahahahhahahaha. Noooo. Hahahahahahhaa”.

But what really got me were the ones that shone a light on the way people think about human rights today. I’ve grouped them by theme and I discuss them below.

But first, a caveat. The tweet was slightly misleading. It may have implied that Taylor Swift was herself somehow violating the law on free speech, which, I agree, would be odd and not really possible within our current legal system. But I said ‘violate free speech principles’ for a reason. Principles are not law. In this context, they are the idea behind a law, the reason that law exists, while not being legally enforceable themselves.

I also said the word ‘bulk’. Bulk is key. It wasn’t the fact that Taylor, or her team, was deleting comments that was the problem. It was the fact that the deleting was indiscriminate. And obviously, the Tweet wasn’t really complaining about Taylor deleting the comments, but rather to her ability to use a programme created by Instagram to bulk delete the comments without even looking at them.

So with that caveat in mind, I move on to the interesting insights on free speech generated by the Tweet itself.

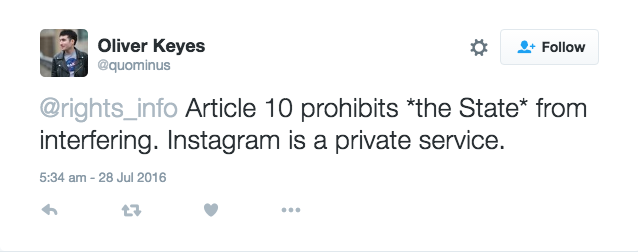

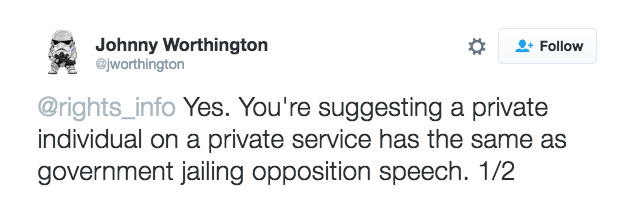

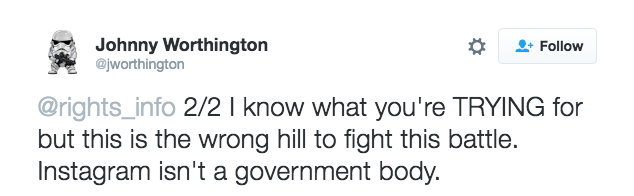

1. Instagram is not the State. Human rights only apply to the State/Government bodies.

It is true that human rights treaties like the European Convention on Human Rights were set up to ensure that state bodies treated their citizens with the standards of respect set out in them. And the Human Rights Act, which brings European Convention rights into UK law, only applies to ‘public authorities’.

But in recent years exceptions to this have developed. For example, private companies, when performing certain contracts awarded by the government – like care homes, hospitals or prisons – have been made to abide by the human rights standards imposed on the government, since they are carrying out the government’s duties on its behalf, or functions which are of a public nature. This year KPMG, one of the ‘big four’ accountancy firms, was initially found to have been acting as a public authority by an English Court, relating to its role in reviewing Barclays bank’s compensation scheme for customers of mis-sold financial products That argument was ultimately dismissed, but is being appealed.

At the same time, there is a growing movement for businesses to comply with human rights principles. Not because it is the law, but because it is the right thing to do. Put it this way: whether or not Facebook is a public authority, it is regularly carrying out a sensitive balancing exercise between the free speech of some of its users versus the desires and even safety of other users. Human rights courts have been grappling with that balancing exercise for decades before social media existed; surely there is a lot to be learned.

So the line between public and private is becoming blurred. And with Facebook and its subsidiary Instagram controlling significant spaces where speech and debate take place, there is at least and argument that human rights principles (if not human rights laws), should apply there too.

2. The idea of defencelessness

The other theme that emerged from the Tweets was one of defencelessness. People didn’t like the idea that Taylor could not somehow ‘lash back’ at her haters by bulk deleting negative Tweets. Fair enough perhaps. And again, maybe the Tweet was unclear, but I just wanted to look into this a bit further.

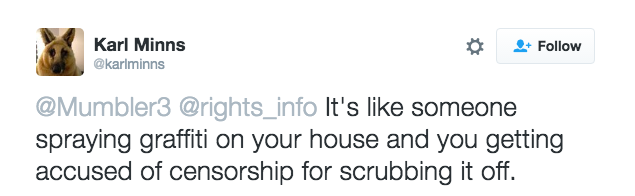

This raises an interesting point. Is Instagram’s new software the same as scrubbing insulting graffiti from the side of your house?

I would say no. If Instagram is allowing a set number of celebrity individuals to use software that indiscriminately deletes comments from a space that is usually a platform for free speech, this isn’t like wiping toxic graffiti from your wall. That would imply contemplation of the meaning of the graffiti, thereby allowing the person writing it their free speech (which you are then free to deny).

The Instagram app could be seen as denying people of their free speech since there is no consideration of the content of the words – just indiscriminate deletion.

Which brings us back to the start. Free speech protects the inherent value in debate and argument. The question for the 21st century is, to what extent do we allow powerful companies such as Instagram, Facebook, and Google, to set the standard on these debates? Without being bound by free speech law, or held to free speech principles in other ways, there is a risk – a risk that the Taylor debate highlights – that companies operate in a way that suits only themselves, with no further thought for the little person.

This post is the author’s opinion, not that of RightsInfo’s.

- For our original article on Taylor & The Great Free Speech Debate click here

- For our poster on free speech click here

- And read our Explainer on why free speech matters