NHS trusts are introducing a new high-tech system which enables staff to monitor mental health service users in their bedrooms via video, without their prior consent.

The Oxevision monitoring system is being adopted by an increasing number of NHS trusts to monitor patients’ behaviour and vital signs. Using an optical sensor, the system allows round-the-clock surveillance of service users’ bedrooms while they are sleeping.

Ostensibly a positive move to help staff protect patients’ wellbeing, the system has raised concerns in relation to protecting patients’ privacy, following reports that some people have been monitored without their consent.

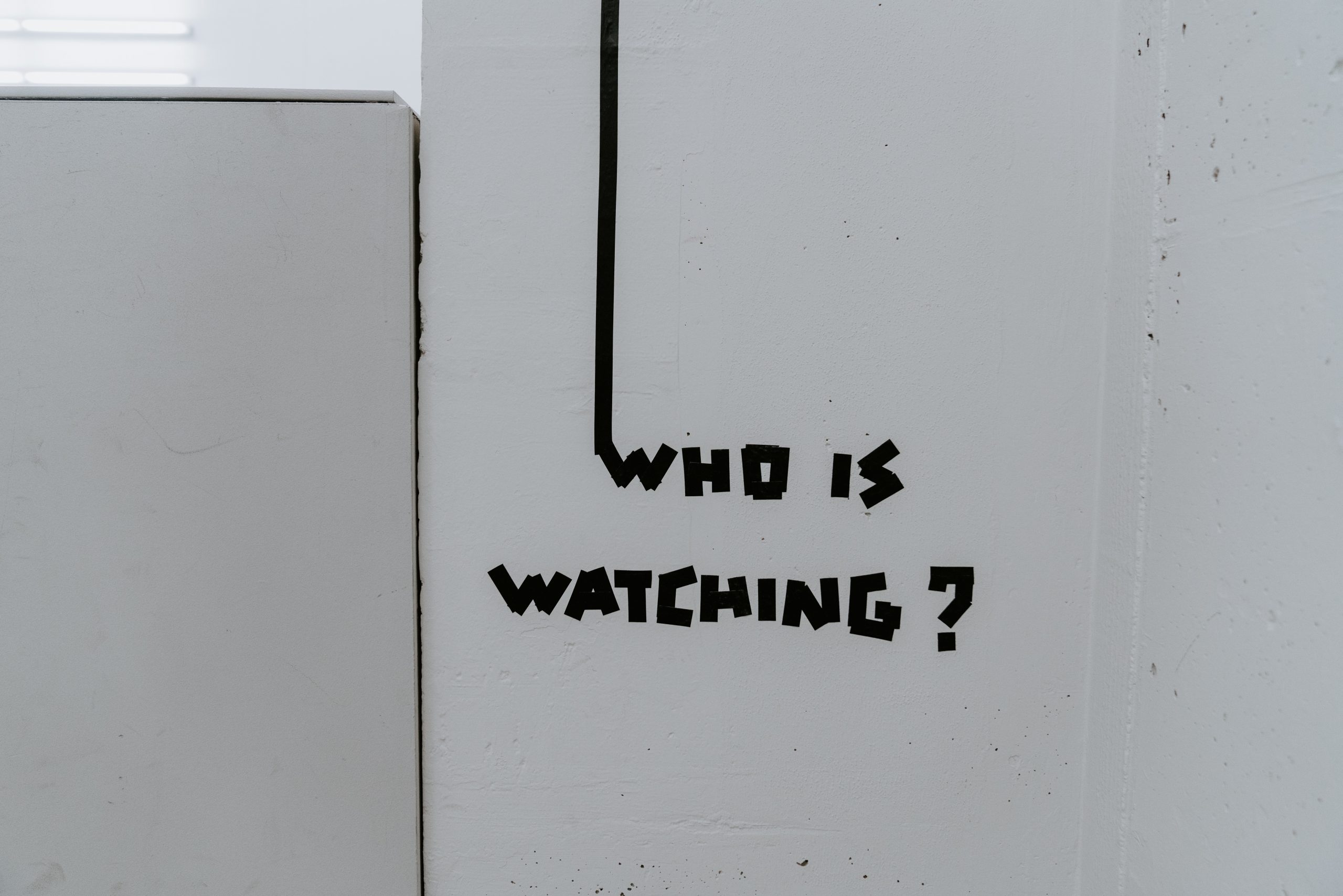

Credit: Claudio Schwarz / Unsplash

The introduction of such a scheme could be interpreted as a breach of Article 8 of the Human Rights Act, which enshrines the right to a private life. While the scheme is designed to improve healthcare provision, if it is not implemented with the utmost care, it may also threaten the right to health, as outlined in the World Health Organisation’s Constitution.

“The patient information leaflet and poster contained no mention of the 24/7 video recording of the room and the few patients that were originally consulted about the pilot of Oxevision did not know about the video recording element of it,” claimed Camden Borough User Group (CBUG) in a statement following revelations that a mental health service user was kept under surveillance without her knowledge while she slept. “As far as we are aware, consent was not consistently obtained from patients, who were being covertly recorded as part of this pilot programme on the ward.”

Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust (CINFT) faced criticism for its introduction of the surveillance system at a recent CBUG meeting. Mental health service users in Camden raised concerns after one of their members, who had spent time on the ward, said that she initially did not know she was being recorded while sleeping.

Credit: Usman Yousaf / Unsplash

At the meeting, CBUG heard that, although CINFT consulted with a few of its service users before introducing the tech, it was claimed it did not warn them about the use of a video feed. The information was not mentioned in the poster and the leaflet it distributed to service users either.

The pilot scheme has now been placed on hold on the CINFT ward but several other mental health trusts have already implemented the scheme and it is not clear if their service users were notified of the video element of the system.

Pennine Care NHS Foundation Trust (PCNFT) announced its introduction of the high-tech system on 18 November. “This new technology complements the vital role of our clinicians and ensures patients who are in a significant mental health crisis are kept safe at all times,” said Rachael Osborne, acute service manager and clinical lead for the project at PCNFT.

Osborne continued: “It will not replace human contact, but it does give us the opportunity to observe our patients from a distance without the need to disturb them unnecessarily, particularly at night. This helps patients to remain calm and settled as we’re able to respect their privacy and dignity, but we can also quickly intervene to support the wellbeing and safety of patients if we need to.”

Credit: Omid Bonyadian / Unsplash

The system tracks the pulse and breathing rate of a service user, as well as when they try to leave their bed and if someone unexpectedly enters the room. It also uses a live video feed of the patient, which is recorded and kept for 24 hours before being deleted.

Oxehealth, which devised the system, says that staff can only access the video feed for up to 15 seconds at a time and only during “vital signs observation”.

CBUG is concerned the video system could endanger the “sexual safety” of service users, but acknowledged that some of its members supported the system because it allowed for fewer interruptions by way of staff checks during the night.

The National Survivor User Network (NSUN) shared CBUG’s concerns, saying that covert surveillance was “not a shortcut to patient safety”. It also highlighted that the system was promoted as part of the NHS Innovation Accelerator, which is the same programme that supported the widely criticised Serenity Integrated Mentoring (SIM) scheme.

“Blanket surveillance is never okay, and especially not as a solution to inadequate staffing levels,” said Mary Sadid, policy officer at NSUN. Whilst some service users may experience positive outcomes as a result of surveillance-based monitoring, this can never justify non-consensual 24/7 blanket surveillance. Consent needs to be specific, individual, informed and ongoing.”

Credit: Etienne Girardet / Unsplash

The Care Quality Commission does not authorise “covert intrusive surveillance”. In its submission to an ongoing inquiry by parliament’s joint committee on human rights into protecting rights in care settings, NSUN highlighted its concerns about Oxevision, warning that it was “concerned that surveillance may be used in lieu of adequate and safe staffing levels”.

Oxehealth says that the monitoring system is being used by a third of English mental health trusts and in “acute hospitals, care homes, skilled nursing facilities, prisons and police forces in the UK and Europe”. A spokesperson added: “We are actively reviewing the materials we share with healthcare providers to help ensure that they have the most up-to-date versions, and are continuing to improve the accessibility of our own materials that service users may choose to access.”

According to a patient experience report, eight out of ten patients experienced a better sense of safety as a result of the technology and another study showed a 22% reduction in self-harm in acute bedrooms.

While the scheme could improve patient care, its introduction without proper explanation of its functions looms over patients’ right to privacy.