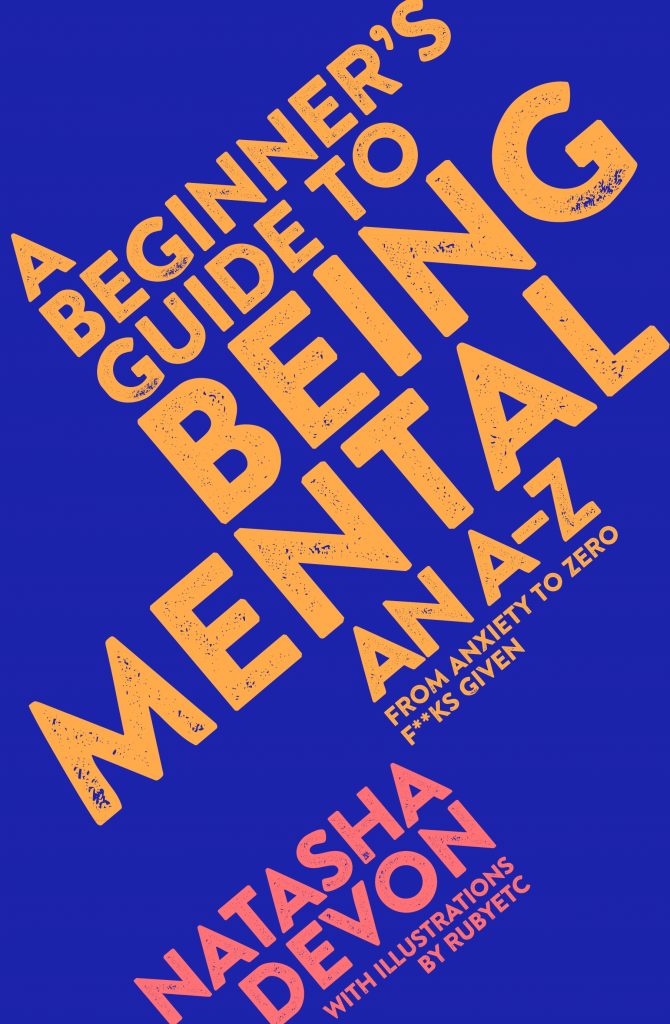

Mental health and body image campaigner Natasha Devon MBE writes about mental illness, pill shaming, and getting fired by the government in her new book A Beginner’s Guide to Being Mental: An A-Z From Anxiety to Zero F**cks Given.

“I very quickly realised that when the government says, ‘we consulted with experts,’ what they mean is ‘we’re going to go through experts until we find the one that’s going to back up what we were going to do anyway,’” Natasha Devon tells me. “And I wasn’t prepared to toe that line.”

We’re talking about her very public sacking by the Department of Education as a children’s mental health champion in 2016. Devon asserts that the relationship soured after she refused to rein in criticism of the government’s policies.

“I think it’s beyond dispute now that I’ve seen the freedom of information request,” she says, “I don’t think anyone would contest it.”

Since parting ways with the government, Devon has continued her work as a mental health and body image campaigner, going to schools and becoming the driving force behind the creation of the Mental Health Media Charter. She’s also authored a new book influenced by her own experiences with anxiety and an eating disorder, called A Beginner’s Guide to Being Mental: An A-Z.

Chatty and straightforward, the book sets out to tackle some of the most contentious issues in mental health care. It runs the gamut from how SSRIs (a type of antidepressents) are prescribed to why men are less likely to access mental health services. Looming over everything is the lack of access to care for people with mental illnesses. Shortfalls in services are just one of the reasons why mental health issues have become a key human rights concern.

Devon tells me how she wants her book to change the conversation we’re having about mental health.

What were your reasons for writing this book?

It began actually as an exploration of emotional vocabulary in the English language. As a student of English, everyone from my primary school teacher right up to my university lecturers, used to say, ‘you’re so lucky you’re studying English!’ I think we’ve got more words than any other dialect. And while that is true, when you look at how the words are apportioned we’ve got a tiny amount of words for feeling and emotions to express ourselves with.

The idea behind the book was to literally get everyone on the same page.

So, it occurred to me that when people misuse clinical terms, like when they say ‘I’m a bit OCD,’ that perhaps they weren’t trying to diminish mental illness but, in fact, it was that the word for how they were feeling didn’t exist. But what that has lead to is a lot of confusion and conversations happening across purposes. The idea behind the book was to literally get everyone on the same page.

Image Credit: Natalie Mayhew (All rights reserved.)

Your book is called ‘a beginner’s guide.’ Why start there?

The beginners in the title references how new the landscape of mental health is. It’s always existed, obviously, but it’s only now that we’re beginning to understand what it is and the impact that it has on us. So, it wasn’t that I was writing to people who had no knowledge whatsoever, though I think you could still read it if that was the case.

I wanted to ask you specifically about young people and mental illness. There seems to be a sense that it’s more difficult now to be a young person than it was in the past in terms of mental health. Why do you think that might be?

I think it’s more difficult to be anyone. But, in particular, if you’re growing up in this culture, that’s particularly pronounced. It’s a perfect storm. it’s a combination of things: the education system, the lack of services, which is still so bizarre to me. The average onset age of mental illness is 14, yet the funding goes into adult services, it makes no sense.

You touch on a number of contentious areas in your book, one of them being SSRIS. Do you feel like they are being prescribed in the right way?

It was so hard to write that chapter in a balanced way. I do think that sometimes medication is prescribed too readily and perhaps as a substitute for therapy and community change, rather than to go alongside. And that’s when it becomes problematic.

I don’t think there should be any stigma associated with saying I’m on mental health medication.

Having said that, there are people who find medication incredibly life changing and I’m one of those people. So it would be hypocritical apart from anything else of me to say that they were wholly bad. And I definitely don’t think there should be any stigma associated with saying I’m on mental health medication.

Why do you think people are so frequently shamed for saying that they’re on SSRIs?

I think there is a myth that they alter your brain chemistry to the extent that you’re not yourself anymore. That was certainly one of my worries before I started taking them. And also, I still think that there is this idea that you should be able to cope. There’s a kind of shame of the weakness.

Why do you think people with mental illnesses are still struggling to get access to treatment?

A big part of it is because mental health budgets remain unring-fenced. That means that when the money arrives with the local authority, they have the option to prioritise something else. So you hear all these stories of money getting lost in transit. I was talking to an early intervention team that work with people with psychosis. They had applied for I think £10,000, not a lot of money in the grand scheme of things, but it would have made all the difference to what they could do. And it just got lost in transit. The Department of Health were saying, ‘well, we sent it,’ and the local authority were going, ‘we applied for it and we got it but we don’t know where it went.’

You worked with the government as a children’s mental health champion. Was it your impression at the time that the government was sincere in its attempt to improve access to mental health services?

It’s difficult to answer that question. I met some Conservative MPs who I do believe were sincere. I actually have quite a lot of time for Nicky Morgan, I think she suffered as a result of Gove’s legacy more than anything that she did. However, I feel that that the overarching agenda was more about PR than about action.

Do you think that the government is going to try and improve access to mental health services in the near future?

Not in the near future. It’s difficult because I don’t want to put them off trying. If we could wave a magic wand all of us would want services to be better but inevitably it does take time and work. I don’t want to fall into a trap where any effort the government makes, people go, ‘that’s not enough.’

Looking at their green paper, it’s very vague and waffly.

But then, looking at their green paper, it’s very vague and waffly. I think one charity estimated that what they have in theory pledged might help a quarter of the young people currently suffering by 2022.

What groups do you think are particularly under-served by the government not allocating enough to mental health care funding?

Poor children. I would also say there are groups of people who are disproportionately affected by poor mental health. So BAME and LGBT+ and children with special educational needs and disabilities.

You write about men not accessing mental health care and the disproportionately high rates of male suicide. Could you talk more about the reasons for that?

I feel that the traditional approach has been quite victim-blaming. We know that men in higher numbers self-medicate with drugs and alcohol and take their own life. The traditional response has been, ‘guys have you thought about not self-medicating and maybe talking?’ And that is an open and shut case of victim blaming. You know, placing the responsibility on the vulnerable person. If men could access help they would. So there’s something that is stopping them.

I mean, there’s no definitive answer, I was talking to CALM the charity about their findings on what it is that men will engage with. Their evidence shows that most men, not all men, but most men don’t find group counselling sessions particularly cathartic in a way that women do. And that they would rather speak to somebody they would naturally gravitate towards anyway, like a sports coach, than go to a professional.

My big challenge to schools, in particular, is to create environments where masculine people find emotional catharsis and to acknowledge that that doesn’t necessarily look like a traditional therapist set up.

You talk a lot in your book about how our environment is making us sick. Could you just tell me more about that?

Yeah, so human beings are pack animals and we evolved that way because we stand the greatest chance of survival in groups. That means we are, by our nature, imperfect. That forces us then to rely on one another and that means that we are most well and most happy in a community.

Community is what is being lost. It’s become an incredibly competitive, individualistic, closed off culture.

And community is what is being lost. It’s become an incredibly competitive, individualistic, closed-off culture. That’s exacerbated but not created by the internet, smartphones, and also by this mindset that you must always want more and never be content with what you have. So all of that is just bashing our mental health constantly.

Reading your book, I did wonder if you were interested in distinguishing between people who suffer from mental health problems as a consequence of a dysfunctional environment and people who have mental illnesses. Or is that an artificial distinction?

I don’t think it’s an artificial distinction. I mean, I don’t think that one or the other is more worthy. But I do think that for some people, and I will include myself in this, mental illness is part of our pathology. I think I was an anxious child and, of course, my environment and my circumstances have played into that, but that propensity was always there. So yeah, I wouldn’t want to go definitive on it but it’s definitely something that occurred to me.

How would you like the conversation that we’re having around mental illness to change?

I just want people to stop saying ‘one in four.’ Firstly, because I don’t believe it. A big campaign I’ve been working on for a very long time is called ‘Where’s Your Head At?’ To create the campaign, we commissioned this huge survey and when it came back, it said that 56% of people have had a mental health issue. I showed that to a colleague of mine who was an NHS psychologist for 30 years, and his exact words were ‘that’s more like it.’ Because he’s always challenged the ‘one in four’ and he’s always said it’s closer to half.

So I think, first of all, because it’s inaccurate but second of all because it’s othering. You know, this is about community and it’s about all of us taking responsibility for our happiness and our mental well-being as a community. I think we need to stop thinking about it as a quarter of people over there who need to sort themselves out.