The bloody wars of the Reformation, the martyrs of Communism, the partition of India: from a quick survey of history it is easy to conclude that people with different beliefs cannot live alongside each other.

In the UK today, we don’t need to look far for examples of this: the Labour Party’s anti-Semitism crisis, Islamophobia during the London Mayoral election campaigns, the Trojan horse scandal, and conservative Christian opposition to gay marriage. In 2015 alone, there was a 60% rise in anti-Semitic attacks in London. This week there has been an explosion of controversy over a French ban on Burkinis in certain towns, with a Muslim woman forced to remove her Burkini on a beach.

But the story is more complicated than that, and creating a pluralistic, tolerant society is both possible and desirable.

The benefits of living in a pluralist society

Faith groups can make an important socio-economic contribution

The Cinnamon Network is a charity that supports local churches to deliver community projects. The Network’s 2015 research – based on a survey sample of 4,440 local faith groups and churches – estimated that groups from all faiths collectively contribute nearly 220,000 social action projects every year, from which 47 million people benefit. The Network estimated that faith groups employ 125,586 staff – making them a significant sector of industry in their own right – and involve nearly 2 million volunteers. That’s over £3 billion worth of support to the UK economy every year.

Faith groups help to tackle the big issues facing our society

- In 2015, Muslims, Jews and Christians held a ‘Coexist’ peace pilgrimage through London in response to the Paris and Copenhagen attacks.

- Leaders from many different faiths came together to tackle climate change by signing the Lambeth Declaration.

- Citizens UK – a coalition of churches, schools, synagogues, trade unions, mosques, universities and community groups – recently won the European Parliament’s Citizens Prize for its grassroots assistance in the refugee crisis.

The combined strength of a multi-faith presence achieves more on larger-scale issues than the voice of one faith alone.

A society that embraces many faiths dilutes extremism and promotes peace

In Britain, a study by the Islamic Human Rights Commission (IHRC) found that 60% of the Muslims it surveyed had witnessed abuse or discrimination directed at fellow Muslims. Many have been subjected to abusive comments, suspicious looks, anti-Muslim graffiti, and attacks on themselves or their property.

In a 2014 research paper, intelligence consultants The Soufan Group found that a key motive behind Western recruits going to fight in Syria is the ‘obligation to help a Muslim community that is under attack’. This has long been one of the central tenets behind extremism. A 2015 IS manifesto explained that part of the rationale behind terror attacks is to create a backlash – making life so difficult for Muslims that they become marginalised and angry enough to turn to violence. They call it eliminating ‘the grey zone of coexistence’.

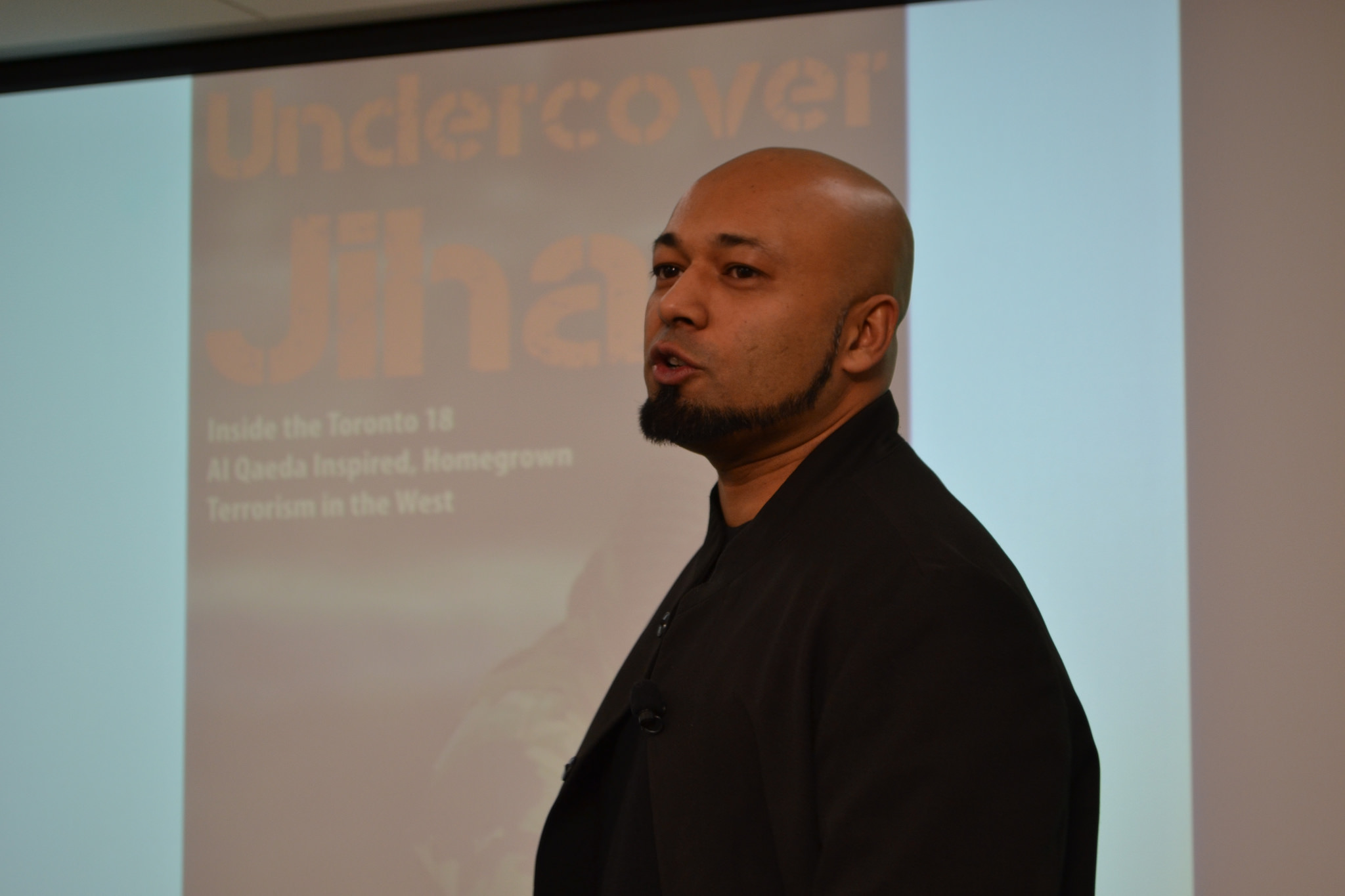

This is supported in testimonies of the recruited and recruiters. An American convert to Islam who was groomed online by extremists was encouraged to fly out to the ‘homeland’ because ‘Muslims are persecuted in the US’. Mubin Shaikh (pictured above), a former recruiter for an extremist Islamist group and now a national security operative in Canada, said “We looked for people who were isolated… And if they were not isolated already, then we isolated them.”

By directing suspicion and hostility towards people of other faiths, we play into terrorists’ hands. We make young people more susceptible to radicalisation. On the other hand, by pursuing a pluralistic society – building real relationships with those of any faith and none – we deprive terrorists of one of their strongest recruitment tactics.

Through dialogue, we refine our own attitudes and beliefs

It’s not just about changing other people’s beliefs. Dialogue with people who believe different things challenges us to refine our own beliefs.

Claire Corley, a Church of England ordinand, told RightsInfo: “My inbuilt individualism is massively challenged by my Muslim friends, who have such a strong sense of family and inter-generational interaction. Our different approaches mean that surface level attitudes are challenged.”

American Rabbi Marc Schneier and Imam Shamsi Ali have spoken about how their friendship allowed them to overcome prejudices. They have written a book on the common ground between their faiths. Their friendship has “impacted both communities worldwide”.

What role do human rights play?

The right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion is protected by Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which has effect in UK law through the Human Rights Act. Article 9 includes the right to manifest religion or belief through worship and teaching, but there are also limits on religious expression, such as those which are necessary to protect public order or the rights and freedoms of others. This promotes peaceful co-existence between people of different faiths and none.

This right is reinforced by two other key laws: the Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 (which makes it a criminal offence to intentionally stir up religious hatred) and the Equality Act 2010 which makes it illegal for certain people (such as employers and service providers) to discriminate on the basis of religion.

But in reality, human rights laws are a backstop, not an end in themselves. Taking steps to co-operate with people of different faiths, enjoying friendships with people of different beliefs, not treating others with suspicion or hostility: these are the things which will make a pluralistic, multi-faith society work.

Learn more about the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion with our infographic poster. Take a look at our introductory explainer of the right to freedom of religion here.