A first-of-its-kind study on life imprisonment has found that there were roughly 479,000 prisoners worldwide serving life sentences in the year 2014 – up 84 percent since 2000. But what does this mean for our human rights?

There’s a lot of confusion over what ‘life imprisonment’ actually means in practice, given that most life prisoners can eventually apply for parole. Coupled with this, many people believe that sentencing is becoming more lenient in the UK. The fact is, though, it isn’t. Sentencing has actually become much harsher.

What is Life Imprisonment?

Image: Bill Ohl / Flickr.

Life imprisonment is a sentence “which gives the state the power to detain a person in prison for life, that is, until they die there“. However, this power is not always exercised. Most life sentences in the UK have a ‘minimum term’ assigned to the individual when they’re sentenced. After they’ve served this minimum term of, say, 20 years in prison, they will be eligible for parole. This means they may be granted early release from prison.

Being eligible for parole does not mean that the prisoner will be granted parole. In fact, they might never be granted it. But, in reality, most prisoners are eventually granted parole on the basis that they no longer represent a danger to society. They will be released from prison, usually with a number of conditions attached – e.g. reporting to a probation officer. If these conditions are breached, they may be sent back to prison.

How Many People are Serving Life Sentences?

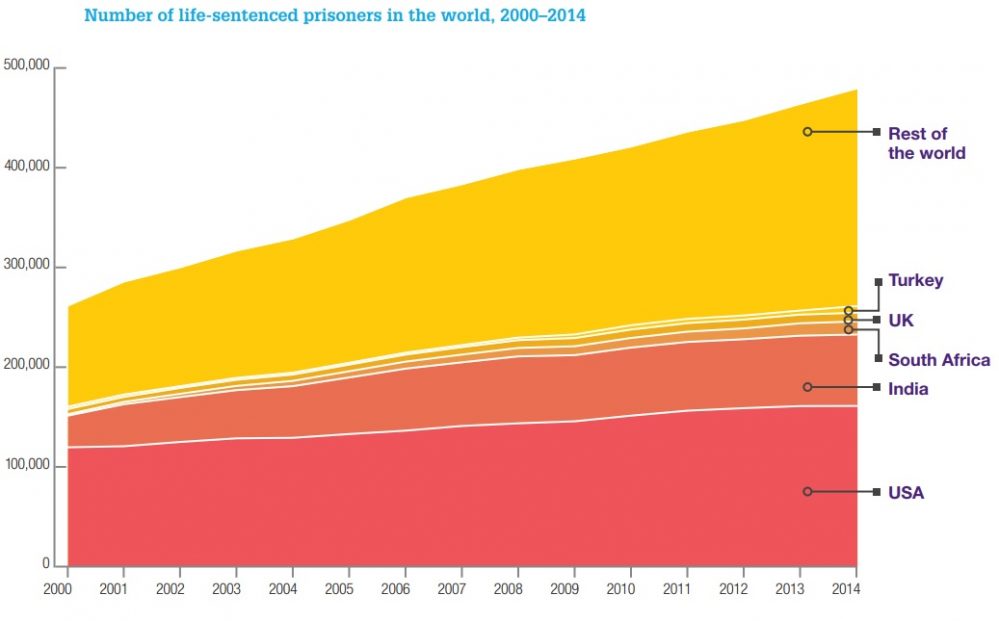

Graph: Penal Reform International and University of Nottingham, A policy briefing on life imprisonment, 2018

As of 2014, the UK had 8,661 prisoners serving life sentences. That’s 11 percent of the whole prison population. It means that, for every 100,000 people in the country, 13 are serving life sentences. Other than a select few Caribbean islands, only two countries – South Africa and the USA – sentence a higher proportion of their population to life imprisonment than we do.

Not only that, but the time individuals are spending in prison before they’re released is getting longer, too. It has more than doubled in the UK, from an average of 9 years in 1979 to more than 18 years in 2013. This demonstrates that parole boards have become much stricter in their assessments of whether individuals still present a danger to society. This made the initial decision to release John Worboys, the ‘black cab rapist’, all the more surprising in some quarters.

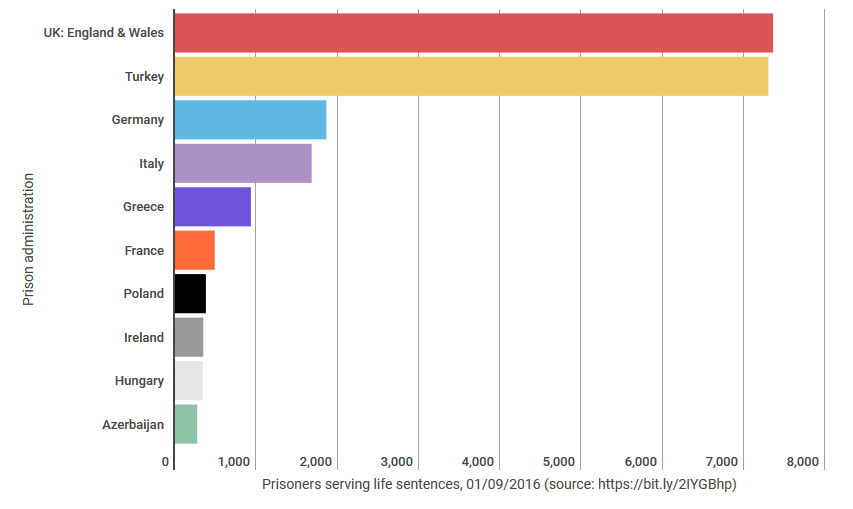

Image Credit: Council of Europe / Infogram

To cut a long story short: in stark contrast to what you might hear in the media, UK sentencing for prisoners is harsher than ever. And harsher than nearly everywhere else in the world.

What About Human Rights?

Nelson Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1964. Image: Ted Eytan / Flickr.

Having your liberty taken away restricts your ability to enjoy some human rights, but it doesn’t void them entirely. Prisoners are human, so they retain their human rights at all times.

Rule 3 of the United Nations Nelson Mandela Rules states that being sent to prison is a punishment in itself, and a prison sentence should not aggravate this punishment. In other words, life-sentenced prisoners have already been punished by being sent to prison, and their treatment in prison should not intensify this punishment. Nonetheless, the implementation of a life sentence can still amount to inhuman and degrading punishment, in violation of Article 3 of the Human Rights Convention. The Article 3 right to be free from torture or inhuman and degrading punishment is an absolute, non-derogable human right. This means that states cannot derogate from their responsibility to uphold this right under any circumstances, even a state of public emergency (such as an armed conflict).

[Life prisoners are] subjected to a very impoverished regime and draconian security measures.

European Committee for the Prevention of Torture report (2016)

Despite this, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture has found that, in many European countries, life-sentenced prisoners are “as a rule” kept separate from other prisoners and “subjected to a very impoverished regime and draconian security measures”. They’re more likely to be placed in solitary confinement, just because of the type of sentence they’re serving.

A Right to Hope

Image: Warren Wong / Unsplash

In an important case before the Human Rights Court, it was found that there might be such a thing as ‘the right to hope‘. While most life sentences in the UK will at some point consider the prisoner to apply for parole, not all will. When an individual is never considered for parole, they have no hope of ever being released.

Long and deserved though their prison sentences may be, they retain the right to hope that, someday, they may have atoned for the wrongs which they have committed

Vinter and Others v. UK, Concurring Opinion of Judge Power-Forde

When life-sentenced prisoners are considered for parole, they are still more likely to be excluded from opportunities to rehabilitate themselves, on the basis that – well, they might never get out anyway. But how can someone hope to be released if they’re not given the opportunities to improve themselves?

As more and more individuals are sentenced to life imprisonment, it’s important to remember that prisoners have human rights too.