There are many celebrations around the 10 June to mark the momentous date in 1918 when women won the vote. But what is often forgotten is that the victory was only for a certain kind of woman – those that owned property.

It took another 10 years before all women, and men, over the age of 21 were able to vote in the UK, with the Equal Franchise Act gaining Royal Assent on 2 July 1928. This legislation enabled millions more women to vote – making it, as RightsInfo has reported previously, arguably the real anniversary of the women’s suffrage movement.

Focussing on one triumphant moment in a societal change – such as 1918’s Representation of the People Act – is great for celebrations and pin-pointing a shift in attitudes, and can herald more change to come.

But it also erases the fact that a third of women over the age of 21 still had to wait another decade before they would be able to vote.

History Is All About Who Gets To Tell Their Stories And Whose Stories Get Erased

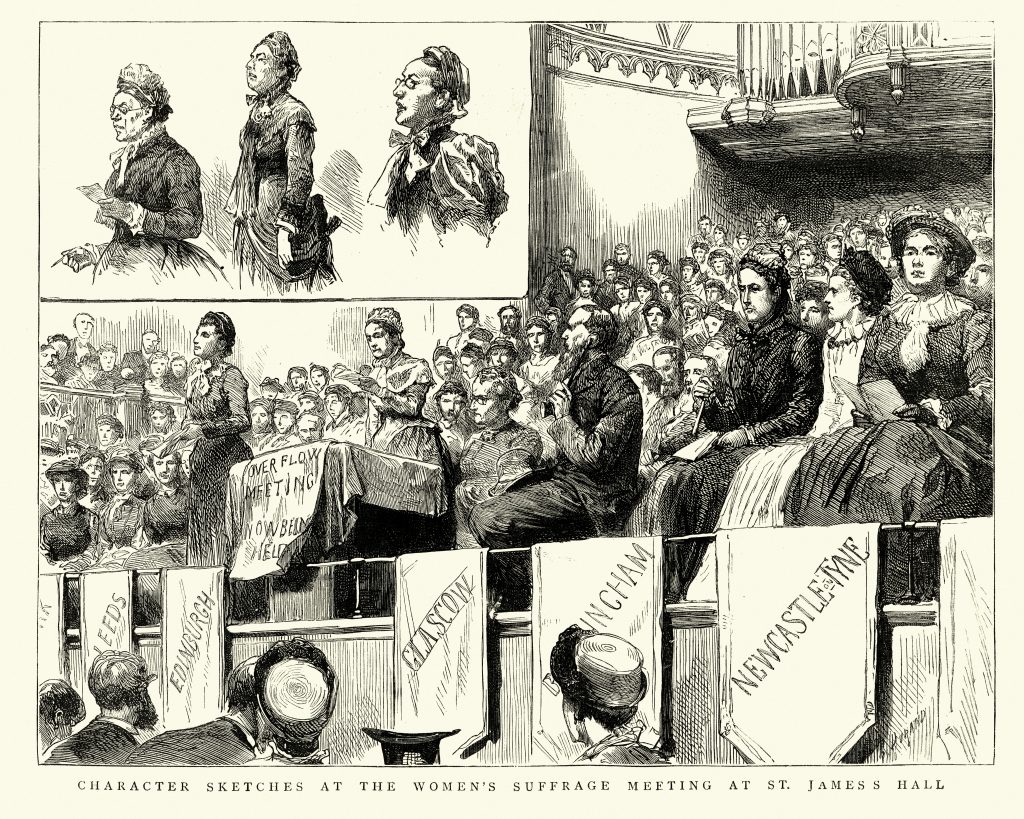

Image Credit: Duncan1890 / iStockphoto

London’s National Gallery is home to a 17th century painting known as The Toilet Of Venus (or ‘The Rokeby Venus”) by Spanish Baroque artist Diego Velazquez. The gallery bought it in 1906 as the last surviving Velazquez nude.

At the time, it attracted huge public attention and debate because such a large amount had been spent on it – £45,000.

However, in the “provenance” of the work that continues to hang in the National Gallery, an important aspect of the painting’s history is hidden.

In the art world, provenance refers to the way the history of an artwork is told. It often lists who has owned it, such as private collectors or institutions, and is also often used in art history to confirm the authenticity of an artwork.

What the provenance in the National Gallery of this painting doesn’t tell us – is that in 1914, a suffragette named Mary Richardson violently attacked it.

She announced it was in protest at fellow campaigner Emmeline Pankhurst’s violent force feeding in prison.

But, when the painting was repaired and rehung, the fact that it had been restored was also missing from the history.

Richardson’s attack was not a one-off but a co-ordinated campaign that led many museums to ban women visitors unless they were accompanied by a man.

The fact the painting has such a significant past attached to the campaign for women’s equality, which was missing from the walls of the National Gallery, inspired artist Nicholas Middleton to do a very special kind of historical restoration. He decided to restore the evidence of the damage and painted a particular kind of photo-realist painting called ‘trompe l’oeil’.

“I was working on a series of tromp l’oeill paintings – and I really liked the potential with working on the Rokeby because I liked the idea of trying to show what a painting looked like at a very particular point in its history,” he told RightsInfo.

“By creating a snapshot of a brief moment in 1914 – uncovering a campaign of political activism that is often forgotten in the triumph of getting the vote.”

In the 1910s, the government showed no signs of moving from its position on women’s voting rights at all. This forced the militant suffragettes to use increasingly extreme tactics to force the government to change the law with a massive programme of civil disobedience. Attacking paintings in galleries was one form of attacking the establishment – who were using violent campaigns themselves like the Cat and Mouse laws to ramp up their tactics.

Image Credit: Black Lives Matter image / Alisdare Hickson

The importance of remembering all these different aspects of history is less to do with focussing on one moment of violence, but instead remembering just how insurmountable a task it felt to those suffragettes, in the face of the total intractability of the government to change.

Sometimes, it can look like it was an easy thing when we celebrate the rights of women to vote – but we need to remember the struggle as much as the achievement. I imagine how difficult it must have been for those suffragettes to see the likelihood of their achievements ever coming to fruition in 1910.

Perhaps it was as hard for them as it seems for us when we try and envisage how the world might look if racial inequality was a thing of the past in every avenue of life. Or if LGBTQ+ rights were established and all the other ways that human rights are eroded in our world were relegated to the history books. But we can all make change and if we come together to help each other – change is possible.