There are around 170 days in the year when children are not in school. For families who are already struggling financially, the additional expense of covering child care costs, activities and meals during this time can push them into serious financial difficulty.

Just the absence of the provision of free school meals alone can cost families around £30 a week.

Holiday hunger has pushed many families into food insecurity, denying children a fundamental right to food.

What Is Holiday Hunger?

A couple and their two children leave the food bank in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, after collecting a three day emergency supply of food, April 2019. They told Human Rights Watch the benefit cap left them unable to pay rent and afford food. Image credit: Kartik Raj/Human Rights Watch

Around three million children are at risk of holiday hunger across the UK. The term holiday hunger refers to children suffering from household food insecurity during the holiday period, meaning that they or their other family members are having to skip meals, or have to reduce the quantity or quality of food that they eat.

The combination of holiday hunger and lack of activities can lead to a ‘learning slump’ for children who rely on free school meals and breakfast clubs during the term time.

Hunger can also have significant long-term effects on children’s physical and mental health, ranging from poor growth to increased incidences of diseases such as Type II diabetes and cancer.

Many food aid providers report an increase in demand from families with children during the holidays. There are also hundreds of holiday clubs that have been set up in order to respond to the demand for both food and activities for children living in food insecure households.

Sabine Goodwin, coordinator of the Independent Food Aid Network, said: “The summer holidays come every year but yet it’s now the new normal for emergency food aid providers to be anxiously preparing for even more adults and children who will need to access their help.

“Wages and our social security system need to provide people with adequate incomes to feed their children without having to resort to charitable food aid, whether it’s the school holidays or not.”

Both of these activities are heavily reliant on donations and volunteers as they try and fill the gaps left by the State, however neither address the underlying causes of food insecurity for these families. Attendance can also lead to children and their parents experiencing stigma from their peers.

Why Are Families Struggling?

Holiday hunger needs to be seen within the wider context of low incomes, especially for those who receive welfare payments.

Charity Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) found in a 2018 report that families on benefits receive only 40 percent of the money they need to achieve the “minimum standard of living“. Child benefit barely covers a fifth of a couple’s cost of raising a child to the age of 18, less than a sixth for a lone parent.

Work is not a protection from poverty either, with 66 percent of children living in poverty coming from working families.

Tax and welfare cuts made over the past decade have been regressive – hitting those on low-income, and who are most vulnerable, hardest. A 2018 review by the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) shows that people with disabilities and ethnic minority backgrounds, among other protected characteristics, have been disproportionately affected by spending cuts.

At this pace, in four years from now 1.5 million more children will live in poverty, the watchdog predicts. The child poverty rate for lone parent households (nine in 10 of which are women) will increase from 37 percent to 62 percent, and households with at least one disabled adult and a disabled child will lose 13 percent of their income. Lone mothers will lose almost one fifth of their annual income.

Many families may also struggle to afford the additional costs of childcare over school holidays. The Childcare Act 2006 places a duty on local authorities to ensure that there is sufficient childcare available for parents of children under 14 years of age.

However, holiday childcare costs have risen by four per cent in Britain since last summer, bringing the average now paid for one week of holiday childcare up to £133.

Whilst Universal Credit can help pay for the additional costs of childcare during the holidays it often arrives too late for families in need as it is paid in arrears.

Only one in four local authorities in England had enough spaces for all children whose parents worked full time, and this dropped to only one in eight for children with disabilities.

What More Can Be Done?

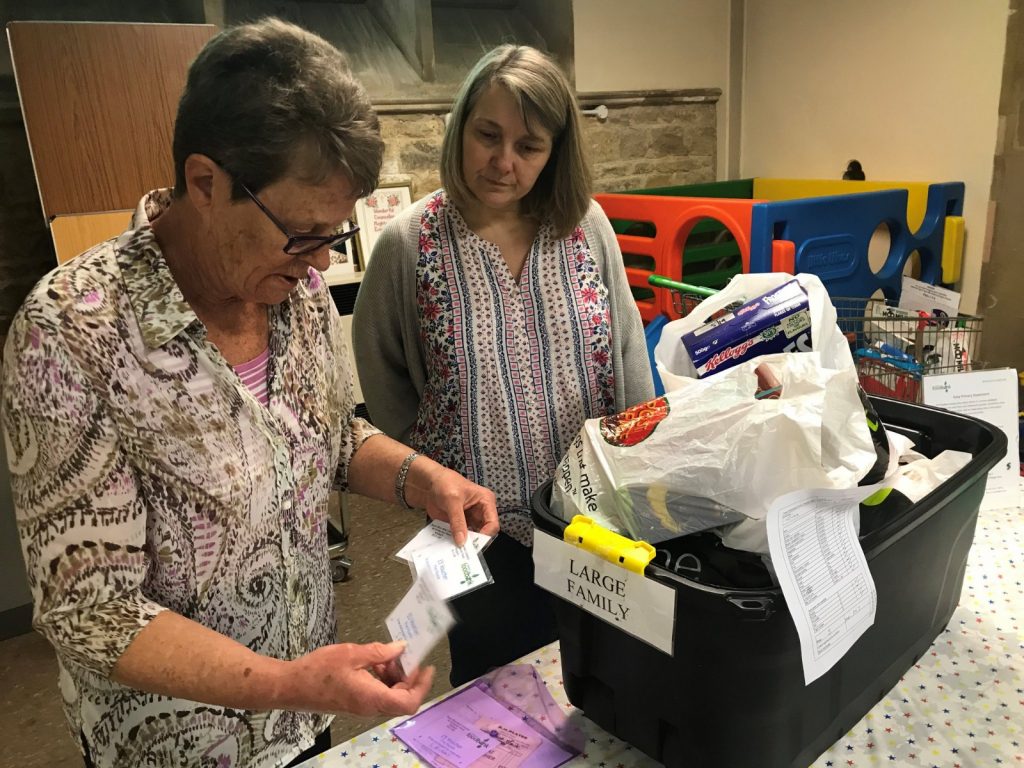

Main Image Credit: Kartik Raj/Human Rights Watch. Volunteers at the Wisbech food bank, Cambridgeshire make up an emergency parcel suitable for a large family.

All children have a right to food, regardless of their immigration status, socio-economic background, or any other characteristic.

Their right to food is protected by the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child – both of which the UK has ratified.

Unfortunately, the government has not bought our socio-economic rights home meaning that whilst we have the right to food, all of us are not able to enjoy this right.

Food insecurity in the UK is not due to a physical lack of food, but rather for many it is due to a lack of financial resources. If the government is serious about tackling holiday hunger, it needs to ensure that wages and welfare payments are in line with the actual cost of living so that families can afford to feed their children 365 days a year.

The government should also be urgently examining specific policies for their effects on child poverty, such as the two-child limit which means families receive no extra Child Tax Credit or Universal Credit for any third or subsequent children born after April 2017. CPAG predicts this will push 300,000 children into poverty by 2023/24.

Hannah-Mae Trow, of the End Hunger UK Alliance, said: “Whilst we welcome funding commitments from the government on holiday hunger, these provisions are only a sticking plaster for a much larger issue.

“End Hunger UK believes that, until the government creates a plan to address underlying causes of holiday hunger and protect every child’s right to good food 365 days a year, the issue of holiday hunger will not go away.”