On Wednesday, 9th March 2016, the EU Parliament in Strasbourg voted, in an overwhelming majority of 613 votes to 30 (with 56 abstentions), to pass a Directive on special safeguards for child suspects. The EU Parliament is separate to the European Court of Human Rights, and we here at RightsInfo usually focus on human rights law, but as this EU Directive impacts on the rights of children, we went along to Strasbourg to find out more…

It was said during the debate that this Directive will strengthen the fair trial rights of the 1.09 million children who pass through criminal justice systems in the EU every year. That’s 12% of all people who are arrested or tried within the EU.

The UK have used their flexible opt out so that this particular legislation does not apply in the UK. However it will soon apply to almost all other EU states.

Here are 5 key things the Directive will do:

1. Providing children with a lawyer is now compulsory

In all EU countries, children have the right to access a lawyer once they are arrested. However, at the moment, children in Cyprus, Ireland, Luxembourg and the UK can waive that right. This means that sometimes children go through the whole criminal justice process without a lawyer.

‘A’, a 15 year old Polish boy, was accused of murder. He was placed in a children’s home and prevented from seeing a lawyer for weeks. He was not informed of his right to remain silent until six weeks after the proceedings had begun, but by then the authorities had already taken incriminating statements from him. He was found guilty and placed in a reformatory for six years. The European Court of Human Rights later found that the actions of the authorities had violated A’s right to a fair trial.

Making it compulsory for countries to provide children lawyers as soon as they are arrested (called ‘mandatory defence’) will make sure children like ‘A’ have access to appropriate advice early in the justice process. Of course, since the UK have opted out, it will not be compulsory to provide children with a lawyer here.

2. Questioning must be appropriate to the child’s age and mental capacity

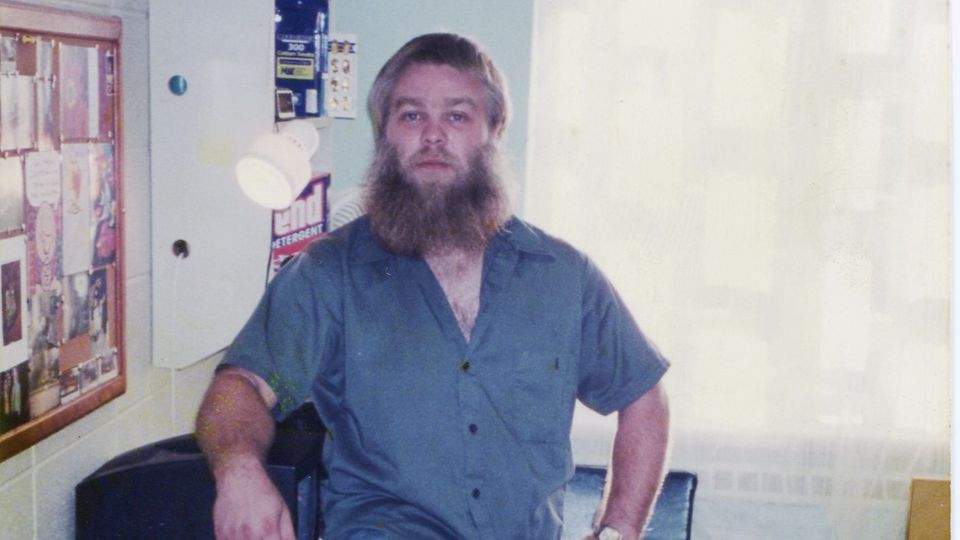

This may seem obvious. But the infamous treatment in the USA of Brendan Dassey (from the TV show Making of a Murderer) is an example of how questioning is not always appropriate in practice, and why taking children’s mental capacity into account is so important.

Questioning by police must also be audio-visually recorded, unless this would not be appropriate. This is important for making sure that procedures are properly followed; the Brendan Dassey video is damning evidence of an abuse of power that we would otherwise have no way of knowing about.

3. Parents must be allowed to assist their arrested children

James Milton* was a 16 year old from the UK who had recently moved to Malta with his mother. He was arrested and taken to a police station where he was questioned aggressively for over four hours, without a lawyer of other appropriate adult present. His mother was refused entry to the interview room despite her frequent requests to see her son.

Not all EU states give child suspects the right to contact their parents when they are arrested by the police. This stops children accessing their key point of support at a critical time. But in response to the Directive, these states will have to pass laws that give children this right.

4. Cases involving children must be treated as a matter of urgency

Would you have wanted false accusations against you to be dragged out for most of your Sixth Form life?

In James Milton’s story (above), his trial did not commence for over a year. The police held his passport throughout that time. He was eventually acquitted of all charges, the Court finding that his accuser’s testimony was “filled with doubts and half truths” and the evidence to support the prosecution case was “grossly lacking”.

The Directive will mean that cases involving children will be given higher priority, and hopefully we’ll hear fewer stories like James Milton’s.

5. Children cannot be tried in their absence

Children cannot be found guilty without having had the opportunity to rebut the grounds for such a conviction. The measure will also help to prevent reoffending, as children who are convicted whilst present at their trials have a better understanding of why they are convicted, so are less likely to re-offend.

The UK feels it does an adequate job in protecting children in the criminal justice system, which is why it has chosen to opt-out of this Directive. It is true that the UK does already have many of the measures in place. The key – and some would say, worrying- gap is with regard to mandatory defence. Can a child truly exercise her or his rights, if they have difficulty in getting a lawyer? You can read interviews from both ends of the spectrum here and here.

* not his real name. Story can be found on p. 20 of September 2014 Joint Position Paper