When Tiverton Primary School in Haringey was forced to revert to home-based learning, it was faced with an immediate problem. While the Government says that schools have a “legal duty” to provide remote education, more than half of the children at the school do not have computers at home.

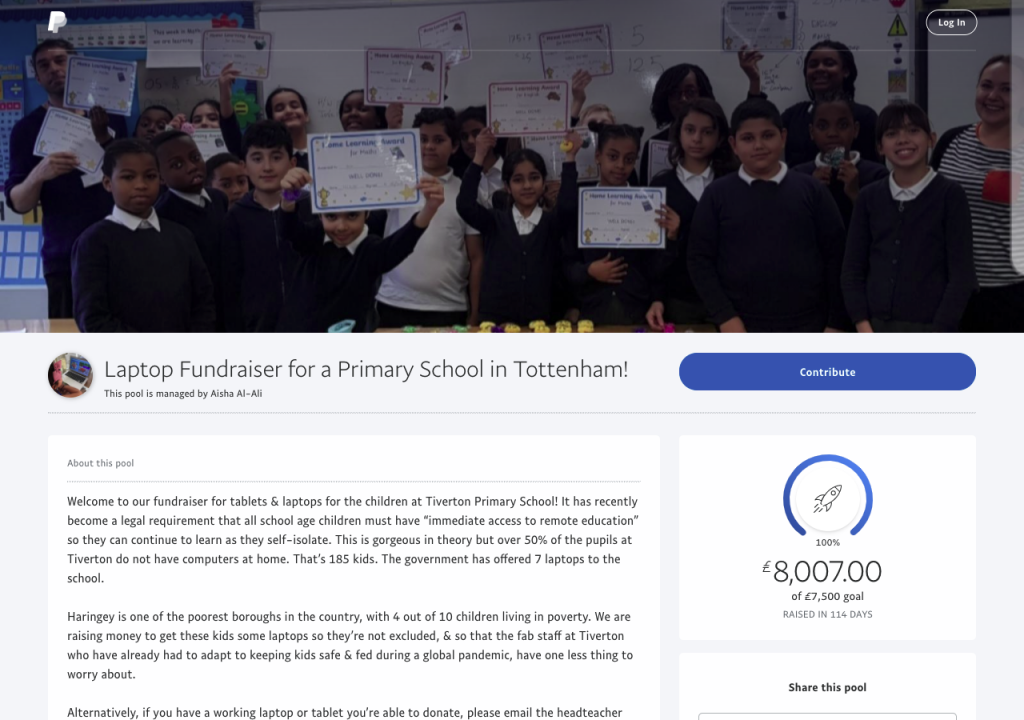

Writing in an urgent fundraiser for more laptops at the school last year, Aisha Al-Ali said that while the Government requirements were “gorgeous in theory”, they simply did not match the reality on the ground. While the Department for Education has set up a scheme to provide computer equipment to schools and colleges in need, demand far outstrips supply. “That’s 185 kids [in Haringey],” Aisha explains, “the Government has offered seven laptops to the school.”

The school was one of the first to be supported by Community Laptops, an organisation that was set up in 2020 to re-distribute electronic equipment from organisations and individuals to schools, people, and families that need devices the most. However, they are not the only school struggling, even if they have received Government help.

“Many schools we’ve spoken to have had issues with the devices supplied by the Government,” co-founder Latifa Akay tells EachOther. “[This includes things like] charging, USB ports falling out, crashing, not booting up, and not being able to handle basic functions like video calls. One school in Greenwich said they’d had to return four of their devices as they didn’t work. Another in Hackney has to return 11 of their received batch.”

A crowdfunder set up to try and fund laptops for a school in Haringey. (Image Credit: Screenshot)

Prime Minister Boris Johnson has said the Government would do “everything possible” to support the move to home learning, and that 560,000 devices were given out in 2020, along with a further 50,000 this year. The PM also said that they had partnered with a number of major mobile phone operators to offer “free mobile data to disadvantaged families to support access to educational resources”.

Over 50% of the pupils at Tiverton do not have computers at home. That’s 185 kids. The government has offered 7 laptops to the school.

Aisha Al-Ali

Government guidelines also state that pupils without a device in England may be deemed vulnerable and, therefore, eligible to return to classrooms. However, it is a move that has been broadly criticised by teachers, who say this could “defeat the object” of lockdown, as hundreds of pupils would return to schools.

In a statement, the Good Law Project, a non-profit organisation that campaigns to achieve change through the use of the law, said the so-called digital divide would have a direct impact on children’s right to health as well as their right to education. The former is protected by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The latter is enshrined in the Human Rights Act.

“We know that poorer and BAME [Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic] families are exposed to higher COVID-19 risks. But now, because of the Government’s continuing failure to arrange for the children of those families to be educated online, they will be exposed to further health risks,” reads the statement. “Their children will have to attend school but wealthier families, who can afford devices and broadband access for their children, can remain at home.”

Their children will have to attend school but wealthier families, who can afford devices and broadband access for their children, can remain at home.

The Good Law Project

The Good Law Project has called off an earlier campaign around the provision of laptops thanks to Government assurances that computer equipment, such as laptops or tablets, would be provided. However, in the wake of what they describe as “ongoing Government failures”, they have now launched a judicial review to ensure adequate devices in a timely fashion.

Not everyone has equal access to devices. (Image Credit: Pexels)

However, for Latifa and the team at Community Laptops this is not a new issue. “The pandemic has shone a light on the digital divide, which was already an issue for millions of people across the UK,” she tells us.

Figures from the Office for National Statistics show that four percent of the UK’s estimated 27.8 million households did not have access to the internet in 2020. Breaking down the data further, research from the University of Cambridge found that only half of households earning between £6,000 and £10,000 a year had home internet access, compared with 99 percent of households with an income of more than £40,001 a year.

Digital poverty is undoubtedly a racialised issue. A lack of support now will lead to continued and further maginalisation.

Latifa Akay

What is more, these figures affect those from minority backgrounds even more. Research has shown nearly half of all BAME households in the UK live in poverty, while people from Pakistani and Bangladeshi households are nearly three times as likely as their White British counterparts to live in low-income households.

“We know that this will disproportionately affect young Black and Brown people who are more likely to live in poverty,” says Latifa. “These will be the same homes that will be more likely to be multi-generational with elderly family members at home or with family members working in front line precarious jobs. This is yet another example of Government decision-making during the pandemic that puts Black and Brown communities at additional risk.”

“Digital poverty is undoubtedly a racialised issue,” she concludes. “A lack of support now will lead to continued and further marginalisation of these communities in the future.”