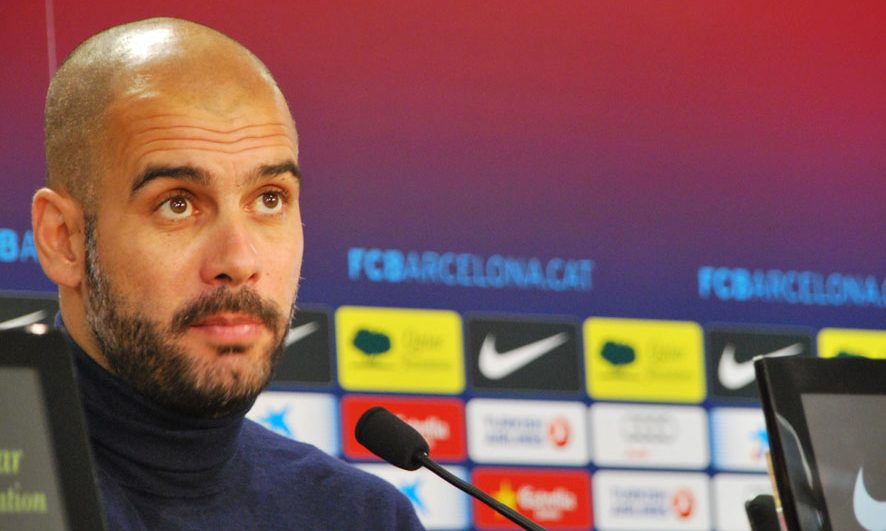

On its own, it’s just a piece of yellow fabric. Attached to the chest of Manchester City manager Pep Guardiola, it’s made headlines around the world.

It’s a yellow ribbon which Guardiola, a long-term supporter of Catalan independence, says he is wearing in support of Catalan activists and politicians imprisoned in Spain since the banned independence referendum in October last year. It’s a gesture that has cost him: just last week he was fined £20,000 by the Football Association (FA), the governing body of football in England.

Guardiola is neither the first nor the last to fall foul of the strict rules that govern what football clubs are permitted to display on shirts. But is it realistic to keep politics out of football? And more importantly, should we?

Political Slogans, Statements and Images

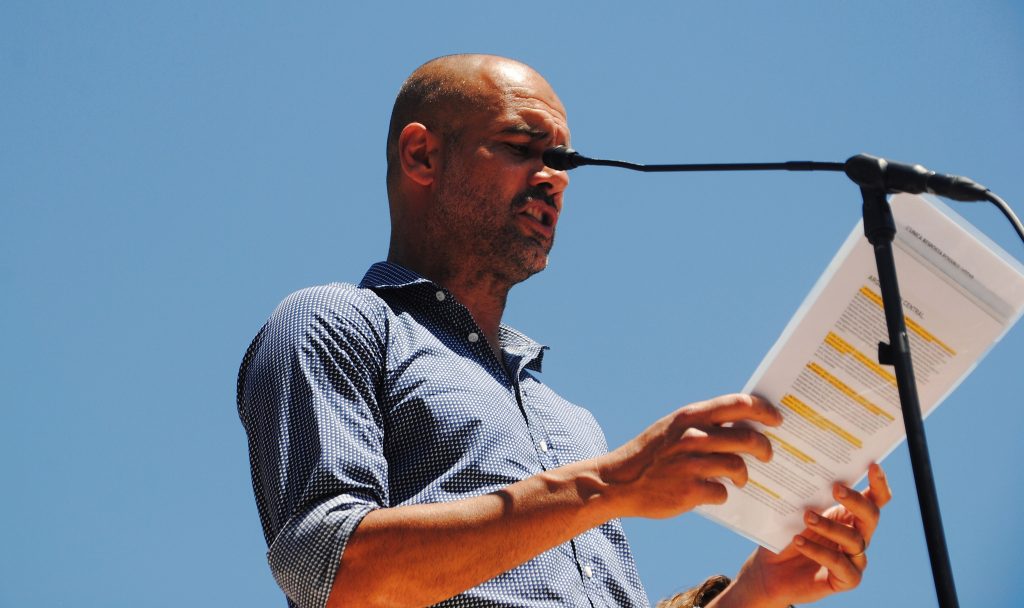

Pep Guardiola at an event for Catalonian independence. Image credit: Assemblea.cat / Flickr

The laws set out by FIFA, the international governing body of football, states that equipment “must not have any political, religious, or personal slogans, statements or images.”

These rules go further than just prohibiting what players can wear on their kit – it also bans players from taking off shirts to reveal undergarments that display political, religious or personal slogans, statements or images.

No political, religious, or personal slogans, statements or images.

Which explains why Liverpool striker Robbie Fowler was fined £900 in 1997 for revealing an undershirt displaying support for striking Liverpool dock workers, or why Egyptian midfielder Mohamed Aboutrika received a warning for lifting his shirt during a goal celebration in 2008 to reveal a t-shirt with the message “Sympathise with Gaza” in protest of Israel’s 10-day blockade.

What Even is Political?

Image Credit: Amanda Slater / Flickr

Image Credit: Amanda Slater / Flickr

The problem is, the answer to the question of whether or not something is political is deeply subjective. Guardiola, for example, has maintained that he is expressing a personal opinion, not a political one, and that his wearing of a yellow ribbon is no different from wearing a pin for a cancer charity.

So far, he’s continued to wear it in pre-match and post-match interviews, covering it up with a jacket when he’s on the touch-line. While the FA has fined him, the European Football Association (UEFA) has not, and so he will be able to continue to wear the yellow ribbon during Champions’ League matches. He and others have argued that the position is inconsistent with the FA’s position on other symbols and emblems.

In 2016, FIFA fined England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland after their national teams wore poppies during matches played around Remembrance Day, deeming it a political symbol. The teams argued that these were not political symbols, and that the wearing of a poppy was an act of remembrance. FIFA later accepted that argument and dropped the ban, and footballers have since played in shirts with pre-embroidered poppies in November matches.

For people from the North of Ireland, and specifically those in Derry, the poppy has come to mean something very different.

James McClean

But not everyone agrees. James McClean, a footballer from Northern Ireland who now plays for West Bromwich Albion, has continually refused to wear a football shirt with a poppy. He believes that the poppy has taken on political symbolism beyond remembrance of those who died in the world wars, and said, in an open letter: “For the people from the North of Ireland such as myself, and specifically those in Derry, the scene of the 1972 Bloody Sunday massacre, the poppy has come to mean something very different.”

He added that wearing a poppy would be “a gesture of disrespect from the innocent people who lost their lives in the Troubles” and has subsequently played in a shirt without a poppy.

Around the same time as the poppy debate was going on, the Football Association of Ireland was fined 5,000 Swiss Francs after the Republic of Ireland’s team wore shirts embroidered with a badge commemorating the centenary of the “Easter Rising” (an event in which over 450 people were killed in a rebellion to overthrow British rule and establish an independent Irish Republic). What was a commemorative action to many was viewed as a political statement by others.

The FA also chose not to take any action when Premier League players wore rainbow laces and captains’ armbands in support of LGBT rights, which could be considered a political gesture of a similar nature to Guardiola’s yellow ribbon.

A Force for Good?

San Francisco 49ers kneeling during the National Anthem. Image credit: Keith Allison / Flickr

Human rights law protects our freedom of expression: our right to hold opinions and express them in public, even if our views might upset or offend people. Preventing footballers from expressing their opinions and beliefs certainly falls foul of that – but it also raises a bigger question of what else is really at stake.

Like it or not, sport is inherently political. Just look at Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ black power salute at the Mexico City Olympics in 1968; the controversies surrounding rugby union tours to Apartheid-era South Africa; Muhammad Ali’s defiance of the Vietnam draft which resulted in him being stripped of his boxing titles. Even more recently, the widespread protests of players in America’s National Football League who chose to kneel during the national anthem rather than stand, to protest against police brutality and racial inequality, ignited a fierce political and public debate.

What all of these events have in common is that they awakened a wider public to issues of injustice and struggle of which they might have been unaware. Football attracts millions of viewers each week, which means millions more people being exposed to issues of fundamental rights and freedoms. Whatever you think of the game itself, that can’t be a bad thing.