Facebook users will now know if their profiles could have potentially been caught up in the Cambridge Analytica Scandal.

The social media company is now issuing notices to its users to inform them if data from their profile might have been passed on, and will also be making it easier for people to see which apps use what data.

It’s a story that’s dominated the news agenda for the past few weeks, and it’s a massive (and somewhat complex) story. Now the dust has started to settle, we take a closer look at the issues and consider how the debate about technology, data, and human rights affects us all.

It All Started With a Quiz…

Stock Image. Image Credit: RawPixel / Unsplash

Stock Image. Image Credit: RawPixel / Unsplash

This whole story started with a personality quiz app on Facebook. The app – built by Cambridge-based academic Aleksander Kogan – was called This is Your Digital Life and was promoted to hundreds of thousands of Facebook Users.

American Facebook users were offered one or two dollars to download and use the personality quiz app. About 270,000 people joined in, and they – unknowingly – brought in their Facebook friends’ data, too.

In a matter of weeks, this apparently innocuous app collected data about approximately 50 million Facebook users. Most of them did not know they were giving away their data – those taking the test did consent to have their data collected for academic use, but their friends did not. None of them was aware of how that data would be used, which means there was no ‘informed consent’, even for those who chose to download the personality quiz app.

Allegations of Influence

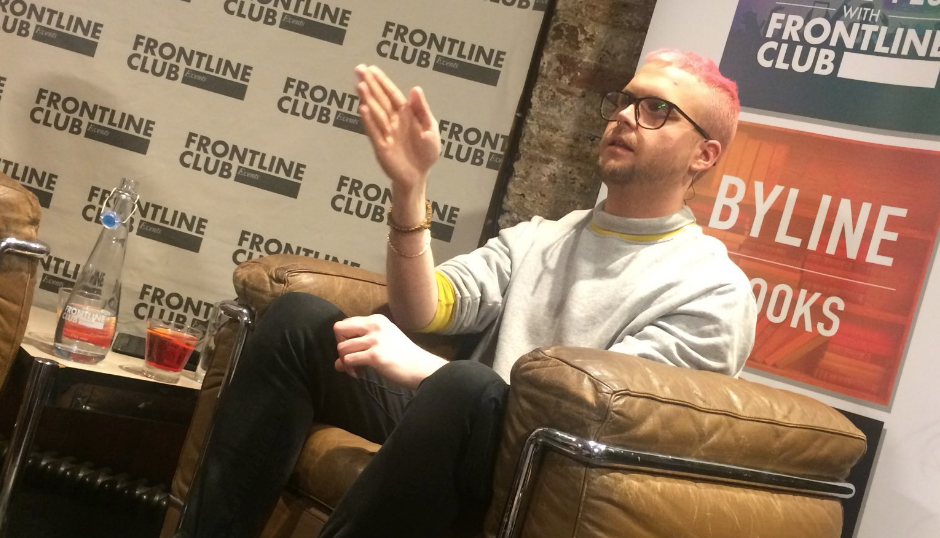

Image credit: Thought Catalog / Flickr

Jump forward to the present and whistleblower Christopher Wylie has been leading international news. The 28-year-old former research director, who has also drawn criticism for his role in the data firm, said Cambridge Analytica got hold of the data harvested by Kogan’s app through an agreement with Kogan’s company Global Science Research.

He also claims this data (supposedly collected for ‘academic use’) became the basis of the data firm’s attempt to use ‘psychographics’ and ‘microtargeting’ to influence voter decisions. The data firm is alleged to have tried to use the bank of data to support Ted Cruz in his campaign to be the US Republican presidential candidate, to influence the outcome of the Brexit referendum, and to boost Donald Trump’s campaign against Hilary Clinton.

For its part, Cambridge Analytica denies any wrongdoing. The company also published a timeline of events, showing when they were made aware that the Facebook data they had obtained from another company had possibly been obtained illegally, and when they deleted it.

Meanwhile, Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg, has admitted they have made “mistakes” and that they will be changing the way they share data with third-party apps. The social network is now facing investigations and hearings from authorities across the world.

‘Cyberwar For Elections’

Image credit: Frontline Club / Twitter

Wylie calls this alleged use of data ‘psychological warfare’ for elections, though others argue this greatly exaggerates the actual impact of the methods employed by Cambridge Analytica in swaying political decisions. For instance, their work on Cruz’s campaign is said to have been a massive flop and their role in the Trump campaign has been described as ‘insignificant‘.

However, Wylie’s allegations aside, the scandal still highlights some much broader questions about dangers to our privacy and our freedoms, making us unsuspecting prey to surveillance and manipulation.

Almost everything we do – keeping in touch, shopping or dating online, listening to music or podcasts, going for a walk or leaving for a trip – can leave a data trail. That data measures just about everything in our daily lives; in the end, we are our data.

Facebook makes money by profiling us and then selling our attention to advertisers, political actors and others. These are Facebook’s true customers

Zeynup Tufecki, University of North Carolina

Machine-learning and algorithms can, through gathering together small pieces of our online data, look into our very souls: personality traits, sexual orientation, political views, mental health status, substance abuse history, and more can be inferred just from our Facebook “likes”. That data is used not only to understand what makes us tick, but also to shape the way we see reality – just think how Facebook News Feed algorithm defines what you read, confining you in an informational ‘filter bubble’. New ways to influence our behaviours are being discovered every day.

Every time we click “I agree” on terms of service, we consent to giving away a little bit more of our data, letting them know us a little bit more and feeding the power of the algorithms.

In 2013, Edward Snowden revealed to the world the scale of governmental mass surveillance and its impact on our fundamental rights. The 2018 Cambridge Analytica shines a light on privacy breaches by corporations, and its impact on our right to vote and our very democracy.

Tech Is Changing The Way We Think About Privacy – And It’s A Wake-Up Call

Image credit: Farzad Nazifi / Unsplash

At its heart, this story is about how technology is changing the privacy landscape at an unprecedented rate. Jason Koebler, editor of Motherboard, an online magazine dedicated to technology, says: “Though Cambridge Analytica’s specific use of user data to help a political campaign is something we haven’t publicly seen on this scale before, it is exactly the type of use that Facebook’s platform is designed for, has facilitated for years, and continues to facilitate every day.

“At its core, Facebook is an advertising platform that makes almost all of its money because it and the companies that use its platform know so much about you,” he adds.

The revolution will come only when people can access and take control over their data and assert their right to privacy

Ravi Naik, ITN solicitors

In fact, while Cambridge Analytica has entered the spotlight for allegedly using the data of millions of people to sell us political candidates, it is claimed that other “data brokers” have been (and still are) doing the very same things to sell us their products. This may come as no big surprise for some. But for many, this story has put the ‘open secrets‘ of personal data protection in the spotlight. It is a wake-up call for all of us.

A Very Real Human Rights Issue

Image credit: Rodion Kutsaev / Unsplash

Our personal data is protected by Article 8 of the Human Rights Convention, the right to respect for your private and family life – at least insofar as its collection and use by governments is concerned. The matter is a little more complex when it comes to use of personal data by private enterprises; the EU’s new General Data Protection Regulation, which comes into force this May, is set to enhance our rights over our own data.

In an effort to recognising the importance of these incoming regulations in the wake of the scandal, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg said: “We intend to make all the same controls (of GDPR) available everywhere, not jut in Europe.”

However, some claim that these data laws don’t go far enough. Ravi Naik, the solicitor who is bringing a legal case against Cambridge Analytica and its parent company SCL, says we need a ‘revolution’ in personal rights over data and that “The revolution will come only when people can access and take control over their data and assert their rights to privacy”.

We cannot let these powerful companies and governments continue to determine our future.

Privacy International

For Privacy International, a charity that works to challenge overreaching state and corporate surveillance, the revolution can’t come soon enough. Referring to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, it says: “We will use the rules that exist and seek new protections to prevent this exploitation of our data. We cannot let these powerful companies and governments continue to determine our future.”

So, what is the way forward from here? Some have reacted to the leak by deleting – or at least trying to delete, as it has proven rather difficult for some – their Facebook profiles. Others highlight how the long-term solution is about getting smarter about everything we do online. However, this should be only the starting point for a broader process of reconsideration of the role of technology in our lives and on the way it impacts on our freedoms and rights.

There is also the bigger question of what to do about elections that were potentially affected by the influencing of voter decisions. The Information Commissioner’s Office has launched an inquiry into data and politics, looking specifically at Cambridge Analytica and Facebook. Separately, the Electoral Commission is investigating what role Cambridge Analytica played in the EU referendum. We must wait to see whether these inquiries are able to restore confidence in how we protect both our right to privacy and the democratic process.