Today’s highly critical report of Sir Philip Green’s leadership of BHS has shed light on the true price of corporate mismanagement. 11,000 jobs and 20,000 pensions are said to be at risk.

The MPs that wrote the report have said Sir Philip Green has a “moral duty” to find a resolution for the BHS pensioners. Concluding that there are gaps in UK company law allowing company directors, financiers and advisers to behave in a way far below the ethical standards that society demands, the MPs said that if businesses fail to behave ethically, further regulation may be necessary.

Separately, Parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights (JCHR) is undertaking a comprehensive review of business and human rights. In this post we look at whether human rights could be the answer in preventing another BHS disaster.

Why is the Committee looking at this issue?

Unlike government and public authorities, human rights treaties do not apply to businesses so they do not have to comply with the high human rights standards set out there. Although companies do have to obey national law, a number of high profile human rights abuses by companies in the nineties and 2000s led people to think that national law is not enough to protect people’s human rights. The BHS scandal is yet another example.

In 2011 the United Nations created the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs – see our post on them here). This placed a duty on the state to protect against human rights abuses by companies, a responsibility on businesses to respect human rights, and the requirement for a remedy for human rights abuses.

On the UNGPs’ 5th birthday, the government announced that the JCHR would review the government’s progress on business and human rights, in particular whether the protect, respect, and remedy formula of the UNGPs is being adequately followed.

What happened on Wednesday?

To progress its investigation, the Committee took evidence from a panel of experts on business and human rights issues. These were:

- Peter Frankental, Economic Relations Programme Director, Amnesty International UK

- John Morrison, Chief Executive, Institute for Human Rights and Business

- Marilyn Croser, Executive Director, Corporate Responsibility Coalition

So, what were the main issues?

Government should take a leadership role on the issue through its:

- Public Contracts: The government spends £236 billion each year buying goods, works and services. To set a good example, the panel said it should prioritise awarding contracts to companies with good human rights records.

- Trade Agreements: The panel discussed the potential opportunity Brexit provides for the UK to include world-leading human rights standards in its new foreign trade agreements.

Improving Legislation

- Tougher criminal laws: The panel said it is currently too difficult to hold companies criminally responsible for corporate human rights abuses. They suggested that government introduce a new crime of ‘failure to prevent human rights abuses’.

- Modern Slavery Act 2015 (MSA): Despite introducing a legal requirement for certain companies to produce a statement saying what steps they’ve taken to ensure there is no trafficking or slavery in their supply chains, there is no central list of companies this requirement applies to, making it easy for companies to dodge this duty.

Redress for victims

- Companies are ‘too powerful’ to prosecute: In 2015 the UK government said it lacked the resources and competence to prosecute Dutch oil company Trafigura, which famously dumped toxic waste near the Ivory Coast in 2006. This was so despite detailed evidence from Amnesty International on the company’s criminal role in the disaster. The panel said the UK needs to be able to prosecute all companies – big and small.

- The National Contact Point (NCP) – the government’s procedure for making a complaint against a company for a human rights violation – was criticised for its lack of enforcement powers. The NCP can only make recommendations to companies – it can’t impose any sanctions.

What next?

The Committee will continue taking evidence and will release a report on its findings in due course. If it decides to take on board the suggestions of tougher laws on corporate human rights abuses and ensuring the government has sufficient resources and will to prosecute corporate offenders, it may be that scandals like this are more avoidable in future. For example, if companies were legally required to protect people’s human rights, under the human right to property, BHS may not have been able to take from people’s pensions without violating that right and facing the consequences. And as we said in relation to the Sports Direct scandal, a stronger business and human rights framework could give workers the ability to speak out against poor conditions and unscrupulous management.

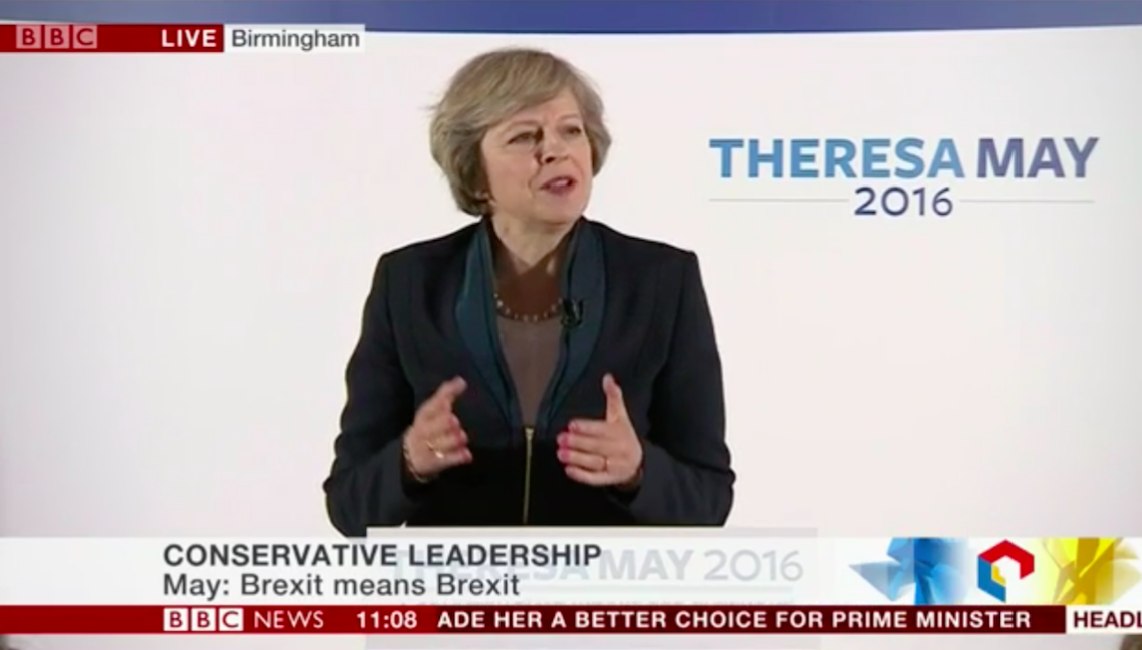

In launching her campaign to be leader of her party and Prime Minister, Theresa May said that she would “get tough on irresponsible behaviour in big business“ and move away from an “anything goes” culture. The government’s response to the JCHR’s report in the wake of the BHS and Sports Direct scandals will test the truth of the new Prime Minister’s statement.

- Watch the whole evidence session here

- For an overview of business and human rights, see here

- For an Explainer on the UN Guiding Principles and Human Rights click here