The Race Relations Act 1968 is marking its 50th anniversary. The landmark equality legislation made it an offence to discriminate against somebody because of the colour of their skin, race, ethnicity or national background in the provision of goods, facilities and services, housing, and trade union membership. It also banned discriminatory adverts and notices. We look back at the Act, its history, and how it informs Britain today.

Until 1965 it was Legal for Pubs to Bar People of Colour

The first piece of legislation in the UK to address racism and racial discrimination was the Race Relations Act 1965, which banned racial discrimination in public places. It also made the promotion of hatred on the grounds of ‘colour, race, or ethnic or national origins’ an offence.

The Act was a response to racial discrimination towards British subjects from Commonwealth countries who had migrated to Britain to fill labour shortages and help rebuild the country after World War II.

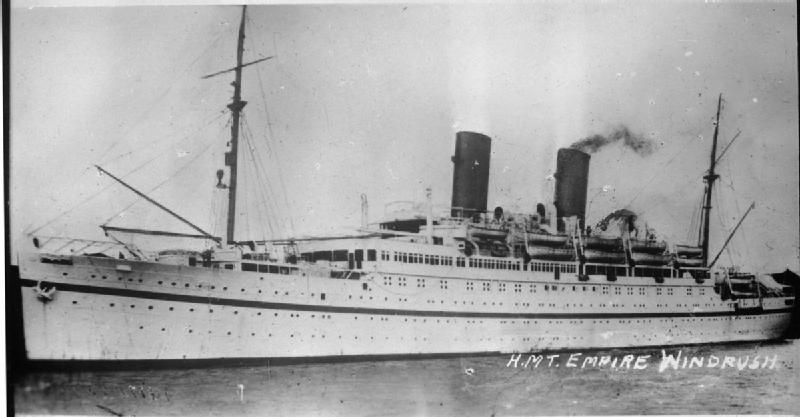

For example, the Empire Windrush, which carried around 490 passengers from the Caribbean, docked at Tilbury docks on 22 June, 1948. By the time the Race Relations Act 1965 was passed, there were approximately one million immigrants from the Commonwealth in Britain.

Empire Windrush Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Empire Windrush Credit: Wikimedia Commons

It was common for immigrants to face outright racism. Pubs would refuse to serve people of colour and notices offering rooms for rent would often say, ‘no black, no Irish, no dogs’ or ‘no coloured.’

Campaigners including the Society of Labour Lawyers, the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination, Fenner Brockway MP and other parliamentarians, pushed for legislation to make racial discrimination illegal. The Race Relations Act 1965 attempted to meet the brief by prohibiting racial discrimination in pubs, restaurants, entertainment venues and public transport services. It also introduced the criminal offence of incitement to racial hatred.

However, it did not cover housing and employment and, for British subjects who had been invited to Britain with the promise of employment and opportunity, the lack of accommodation was a real problem.

As a result, campaigners felt the legislation was a letdown.

The Race Relations Act 1968 Extended to Housing

James Callaghan was the Home Secretary who passed the Race Relations Act 1968 Credit: Wikimedia Commons

James Callaghan was the Home Secretary who passed the Race Relations Act 1968 Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The Race Relations Act 1968 extended the provisions in the Race Relations Act 1965 to cover goods, facilities and services, trade union membership and, most significantly, housing accommodation. It also banned advertisements and notices which had the intention to discriminate – such as the notorious ‘no blacks, no Irish, no dogs’ notices.

For the Labour government, led by Prime Minister Harold Wilson, which passed the 1968 Act, the legislation was an opportunity to lead by example and establish that people should not be treated differently on the basis of skin colour.

What the bill is concerned with is equal rights, equal responsibilities and equal opportunities, and it is, therefore, a bill for the whole nation and not just for minority groups.

James Callaghan, Home Secretary, April 1968

At the second reading of the bill, James Callaghan, the Home Secretary, stated:

“We are called upon to lead the country and our fellow men and women away from a prospect of strife and enmity and towards a society in which we shall live in freedom and in peace with each other, no matter what may be our race or our colour.

“What the bill is concerned with is equal rights, equal responsibilities and equal opportunities, and it is, therefore, a bill for the whole nation and not just for minority groups.”

However, it was again felt that the legislation did not extend far enough – with cases of racial discrimination in employment initially being referred to the Department of Employment and Productivity and then to ‘suitable industry machinery’.

The legislation also failed to meaningfully address racial discrimination in public services.

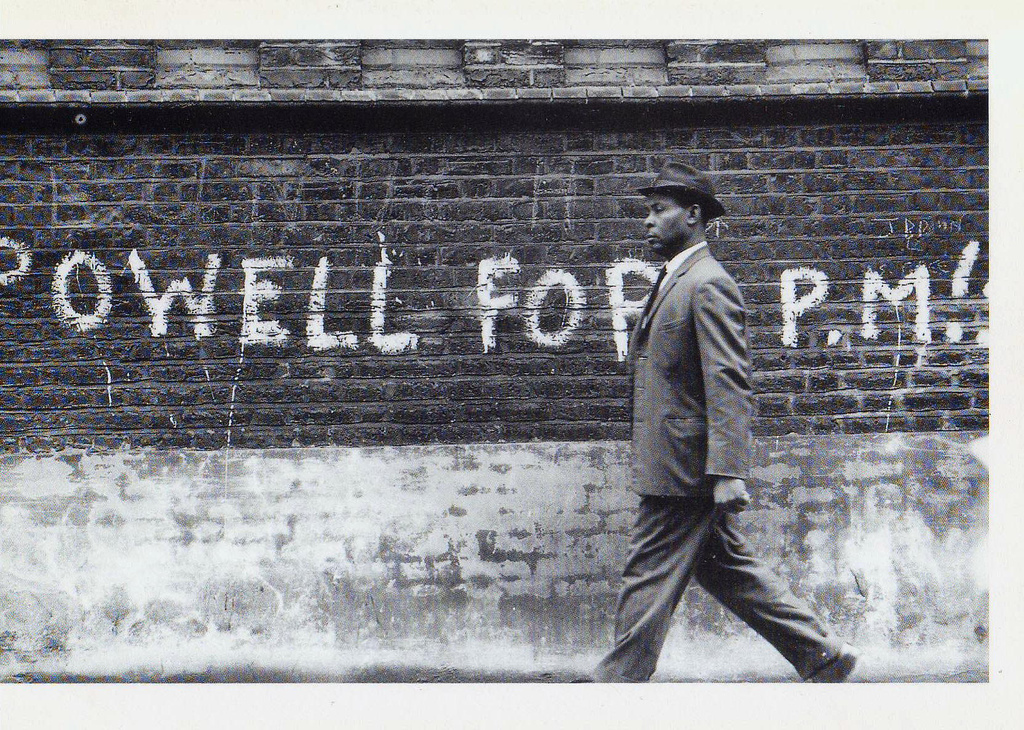

The Legislation Led to Enoch Powell’s Divisive ‘Rivers of Blood’ Speech

Enoch Powell Credit: Allan Warren Wikimedia Commons

Enoch Powell Credit: Allan Warren Wikimedia Commons

On 20 April, 1968, three days before the second reading of the Race Relations Bill in the House of Commons, Shadow Secretary of State for Defence, Enoch Powell, delivered his now notorious ‘rivers of blood’ speech to a closed Conservative Association meeting in Birmingham.

The key passage in the Powell’s diatribe directly references the legislation: “For these dangerous and divisive elements the legislation proposed in the Race Relations Bill is the very pabulum [food or fodder] they need to flourish. Here is the means of showing that the immigrant communities can organise to consolidate their members, to agitate and campaign against their fellow citizens, and to overawe and dominate the rest with the legal weapons which the ignorant and the ill-informed have provided.

“As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see “the River Tiber foaming with much blood.”

I have told Mr Powell that I consider the speech he made in Birmingham yesterday to have been racialist in tone and liable to exacerbate racial tensions.

Conservative party leader Edward Heath, April 21, 1968

The next day, Conservative party leader Edward Heath dismissed Powell from the shadow cabinet and said: “I have told Mr Powell that I consider the speech he made in Birmingham yesterday to have been racialist in tone and liable to exacerbate racial tensions. This is unacceptable from one of the leaders of the Conservative Party.”

What Has Followed?

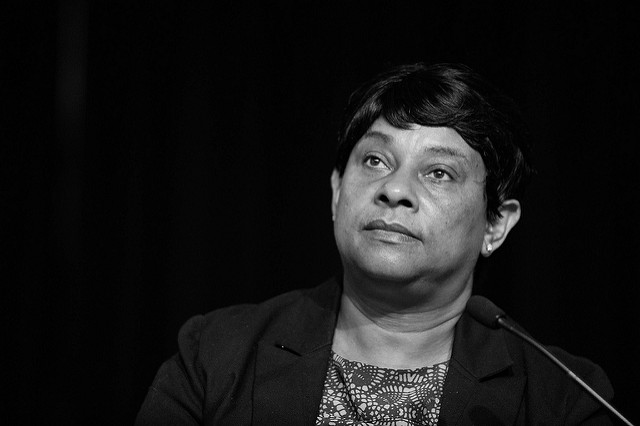

Baroness Doreen Lawrence, who’s son Stephen Lawrence was murdered in a racist attack in 1993 Credit: Southbank Centre Flickr

Baroness Doreen Lawrence, who’s son Stephen Lawrence was murdered in a racist attack in 1993 Credit: Southbank Centre Flickr

It wasn’t until eight years later and the Race Relations Act 1976 that laws banning discrimination in employment and education were introduced. However, although the Race Relations Act 1976 was considered to be advanced and robust for its time, it did not address racism and racial discrimination by public authorities in fulfilling their public functions.

In 1999, the publication of the Macpherson Inquiry into the Metropolitan Police’s investigation of the 1993 murder of black teenager Stephen Lawrence, led to the Race Relations (Amendment) Act 2000. The move finally extended racial discrimination legislation to cover the police and public authorities.

Sir William Macpherson’s damning report on the Metropolitan Police’s botched investigation into Stephen Lawrence’s racist murder at a bus stop in Eltham, South East London, found that the police force was ‘institutionally racist‘.

All of the race relations acts have now been brought under the Equality Act 2010. The Human Rights Act 1998, which incorporated the Human Rights Convention into UK law, also protects against discrimination on the basis of race (as well as other characteristics).

Although over the last 50 years there has been significant progress in legislation championing equality and providing legal recourse to people experiencing racial discrimination, it’s also abundantly clear that racism and racial discrimination is very much part of Britain today. Which begs the question, what will the UK’s racial discrimination laws look like 50 years now?