Calls to scrap a model that unites police and community mental health services are gaining traction. Concerns have been raised that this approach to treating mental health patients threatens human rights.

In April 2018, the Serenity Integrated Mentoring (SIM) was selected for a national rollout and has since been adopted by 23 NHS mental health trusts in England. Designed to help police and A&E services cope with mental health patients who regularly call emergency services or attend A&E after self-harming, attempting suicide or threatening to take their own lives, the system has drawn heavy criticism.

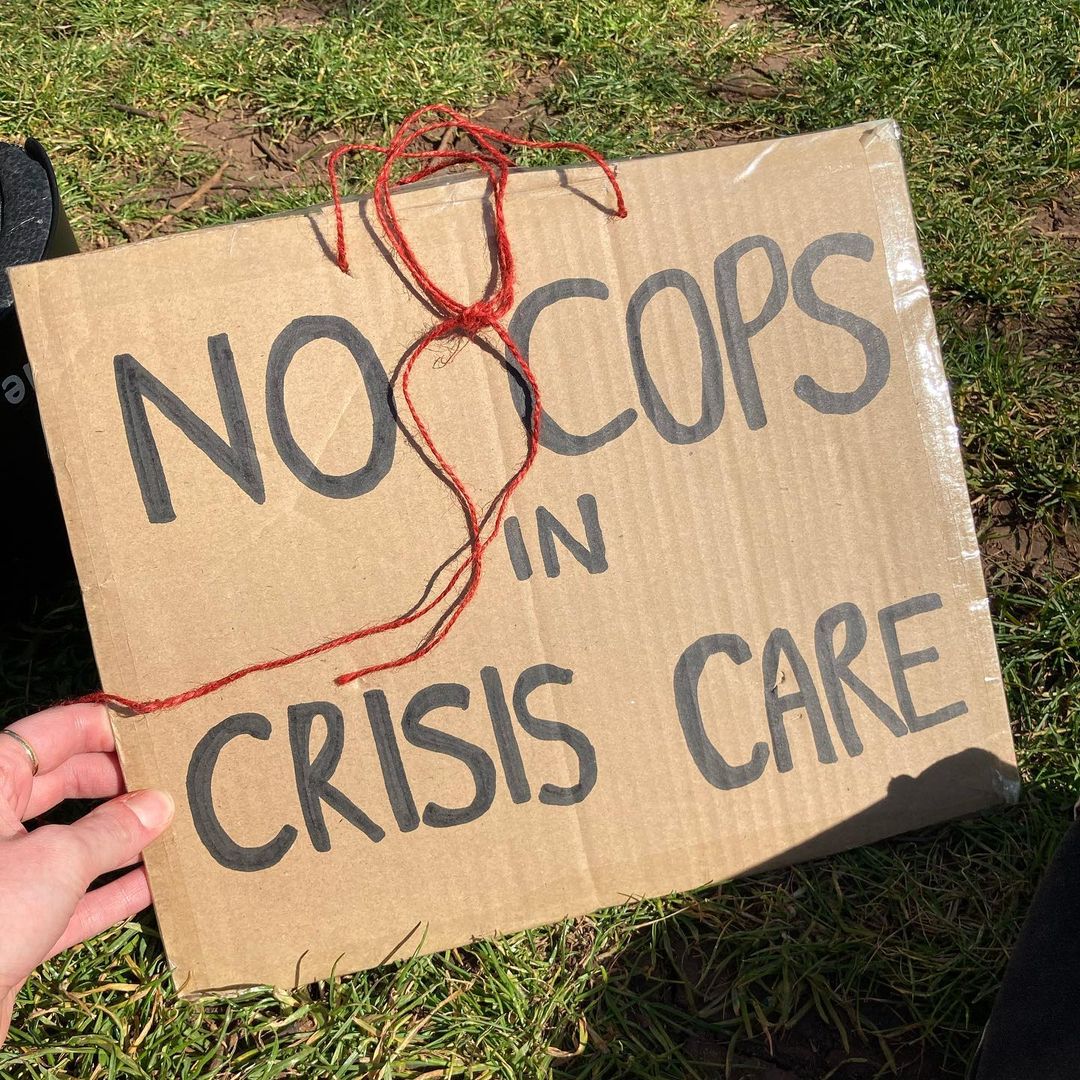

The StopSIM coalition, a collective of disabled, neurodiverse and mentally ill individuals campaigning for the eradication of SIM, considers the model “unlawful, unethical and unacceptable.” The group is calling for it to be halted immediately, and for an independent inquiry and review to be conducted as soon as possible.

What is SIM and how does it work?

Photo by Emily Underworld on Unsplash

Created by former police officer Paul Jennings, who is not a mental health professional, SIM brings together a mental health lead nurse and a police officer to support those with complex mental health needs who “regularly” come into contact with services.

Aimed at helping patients with “high intensity” mental health needs manage their behaviour, supposedly reducing the impact they have on emergency services, individuals are assigned a police officer who contacts them twice a week to create a plan for managing their symptoms. These officers are called ‘High Intensity Officers’ and they receive three days of initial classroom training. They then have full access to service users’ medical records and can share police records with medical staff.

Recently, the company behind SIM, the High Intensity Network, has become defunct with the website showing a 404 error. Several mental health organisations and professional bodies have condemned The High Intensity Network, calling for inquiries into how the system was implemented, as it was not designed by psychiatrists or psychologists.

According to a report by iNews, a spokesperson for NHS England said they do not know if SIM has been suspended or, if it has, what will replace it and when.

An attempt was made to contact Jennings for an interview but, according to his email bounce back, “The High Intensity Network is now closed permanently. Thank you to everyone who supported our amazing eight year journey and to the service users who made such great progress and were such an inspiration.”

What are the concerns?

Credit: StopSim

“There are a great many people within our community, particularly those with chronic mental health disabilities who require long-term support, who are deeply concerned about contacting emergency services for fear of being put under the SIM model,” says a spokesperson from StopSIM.

Several organisations have come out against the implementation of the SIM scheme and are campaigning for a full inquiry to be conducted into the system’s impact on mental health patients. They believe that vulnerable patients are being unjustly denied treatment.

The StopSIM coalition does not believe the scheme can be reformed. “Because the SIM system was founded by a police officer and is founded on principles that are not trauma-informed, it is not apparent that there is a way to remodel SIM to remove the harm it can cause,” says its spokesperson. “The involvement of police in mental health care to drive down demand and cost of emergency services is not a system that has been designed with a view to compassionate care for the patient.”

StopSIM considers the scheme a breach of the Equality Act because it allows for discrimination against people on the grounds of disability – like a long-term mental health condition – gender identity, race, and sexuality. They also state that it breaches Article 2 – the right to life – of the Human Rights Act 1998 due to SIM’s policy on withholding potentially life-saving care from frequent users of services.

The National Survivor User Network (NSUN), a network of people and groups with lived experience of mental ill health, distress and trauma, supports StopSIM’s campaign to bring an end to the scheme. “It is extremely concerning that people could feel forced to hide their self-harm or suicide attempts from services out of fear of being placed under a coercive model of ‘care’ with the potential for police contact,” says Amy Wells, Communications and Membership Officer for NSUN. “This is especially true for those from minoritised or racialised communities for whom the possibility of police brutality and discrimination is a very real fear.”

There are also concerns about the potential of GDPR breaches because SIM allows “sensitive data,” like medical records and financial information, to be shared between services. “SIM also appears to largely target women who have received a diagnosis of ‘personality disorder’ and have experienced sexual abuse or trauma,” adds Wells. “Overall, this ‘model of care’ can be considered discriminatory, neglectful and harmful.”

Tim Kendall, NHS National Clinical Director for Mental Health and Claire Murdoch, NHS England’s Mental Health Director, have both written to mental health trusts asking them to review their use of the scheme.

What’s next?

Early in 2021, the government announced that it was allocating £500m to its Mental Health Recovery Action Plan. Responding to the pandemic and the resulting increase in patients accessing mental health services, the government pledged that patients will have more choice in their care. However, there are concerns that unless the flaws in mental health services are corrected, other controversial interventions could be rolled out to replace the SIM scheme.

StopSIM is continuing to call for an independent inquiry and evaluation of the scheme, as well as a complete halt to the use or expansion of SIM across the NHS. You can find out more about their work here.