Lord Alf Dubs, a Labour peer and lifelong campaigner for refugees, recently announced a new public endeavour to inject more compassion, kindness and empathy into British politics, particularly centring on allowing and assisting refugees to a place of safety in the UK.

He has dedicated several decades working and advocating for refugees, though as the European Refugee Crisis has unfolded over the last few years, his work has gathered significant momentum – in particular, his efforts regarding an amendment to the existing Dublin III arrangement supporting unaccompanied child refugees.

Lord Alf Dubs at his office in Westminster. Image credit: Jem Collins / RightsInfo

However, alongside myriad other problem, as the UK heads towards leaving the European Union early next year, there are concerns that the UK would no longer be obliged to abide by current European legislation, Dublin III, which allows refugees to seek asylum in the UK. Dubs is focused on ensuring that our government continues to support the world’s most vulnerable people in the wake of Brexit.

When we meet in his office in Westminster to discuss the UK’s involvement and the impact of Brexit on the ongoing refugee crisis, Dubs is buoyed by his recent trip to Lesbos where he visited the refugee camps, met with the Greek authorities and observed first-hand the day-to-day difficulties faced both on the ground and behind the scenes.

It’s a desperate situation. We want the government to be more generous.

Lord Dubs

Lord Dubs’ office is piled high with books, articles, letters and scattered paperwork. He talks about the need to sustain safe and legal passages for refugees with a palpable passion deeply rooted in his personal, political and professional experiences. As a young child, Dubs sought refuge in the UK from Nazi-occupied Europe 80 years ago after arriving on the Kindertransport, which transported 10,000 mainly Jewish children from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia to Great Britain.

Kindertransport memorial statue at Liverpool Street Station. Image Credit: Harry Pope Flickr

Kindertransport memorial statue at Liverpool Street Station. Image Credit: Harry Pope Flickr

He is adamant that the UK is able to support far more refugees than we have previously allowed to settle here. “It’s a desperate situation. We want the government to be more generous. The trouble is public memory is so short,” he says.

Dubs is referring to three-year-old Syrian boy Alan Kurdi, the child refugee whose drowned body washed up on a Turkish beach in September 2015, much to the horror of the international media at the time.

The European Refugee Crisis in 2018

Abandoned life jackets on the island of Lesbos, Greece. Image Credit: Brainbitch Flickr

Abandoned life jackets on the island of Lesbos, Greece. Image Credit: Brainbitch Flickr

Three years after the United Nations declared the crisis had resulted in the highest levels of displacement and refugee applications since World War II, not much has changed. Vast numbers of displaced people continue to seek asylum and safety in Europe in the hope of reuniting safely with loved ones away from persecution and terror, despite the arduous journey and unpredictable process of negotiating complex international political and geographical hurdles in order to gain asylum, especially in the UK.

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), estimates that 109, 918 people have sought refuge by sea routes to Italy, Spain and Greece so far this year, forced to leave their countries, families and loved ones behind in favour of the great risks and uncertainties of seeking asylum.

No one puts their children in a boat, unless the water is safer than the land

From Warshan Shire’s poem Home

It’s a difficult decision poignantly attested to by Warsan Shire, a young Somali-British poet, whose poem Home reflects on fleeing conflict: “No one puts their children in a boat, unless the water is safer than the land”.

The dire practicalities and overwhelming demand of the situation means that refugees arriving on the shores of Europe are usually stuck in limbo in camps for months into years on end. Suicide and mental ill health are rife, with stories of children attempting to hang themselves and others preferring to risk the overwhelmingly dangerous journey back to Syria or go with human traffickers rather than live in refugee camps and continue futile attempts to claim asylum in mainland Europe.

Dubs was shocked by what he saw on his visit to Greece, seeing young children kept behind barbed wire, screaming and crying in desperation.

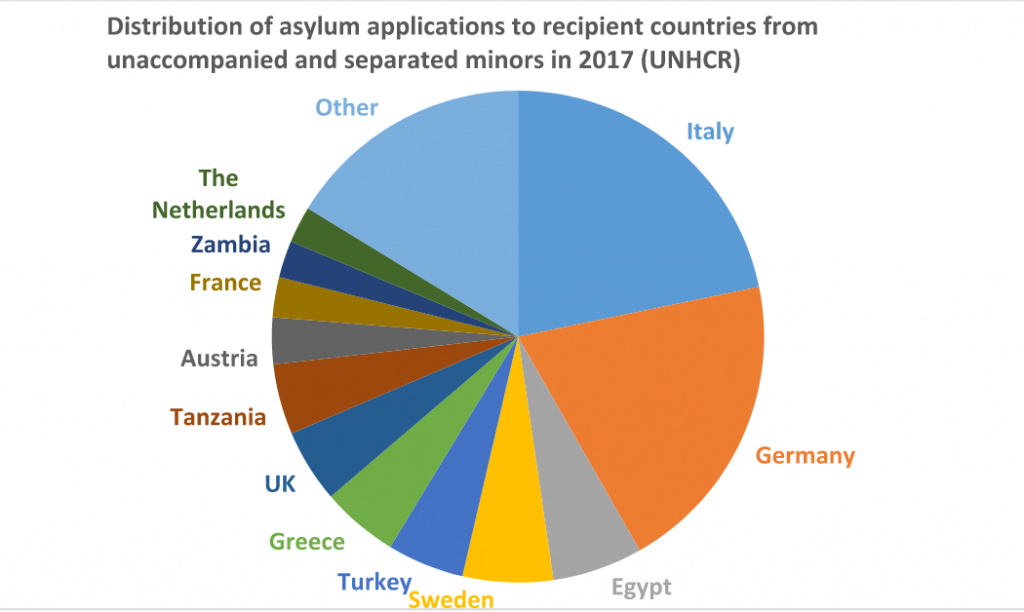

The UK’s efforts towards refugees and asylum seekers have been heavily criticised over the last couple of years, especially when compared to the efforts of our European neighbours. According to UNHCR figures, the UK received substantially fewer asylum claims from unaccompanied and separated minors last year compared to many of our European peers.

Research by the Equality and Human Rights Commission also emphasised that the UK is in danger of breaching basic international human rights by not addressing simple vulnerabilities such as access to healthcare, stigma and the socio-economic deprivation preventing access to jobs and financial insecurity that disproportionately affect refugees and people seeking asylum here.

The UK’s failings are two part; first, leaving more vulnerable people overseas in limbo when we could help them but, secondly, not sufficiently supporting those who are here.

What Can We Do?

Children at a refugee camp on the island of Lesbos, Greece Credit: Steve Evans Flickr

Children at a refugee camp on the island of Lesbos, Greece Credit: Steve Evans Flickr

Dubs is adamant that we have a responsibility as one of the wealthiest nations on the planet to support vulnerable people seeking safety and he firmly believes that family reunification is one of the best ways to bring child refugees to safety.

Most of his activism focuses on promoting reunification strategies and advocating for refugee children and he has seen its benefits first hand a number of times: “It’s giving that young person a chance in life,” he says.

Dubs talks about how refugees are often desperate to be reunited with their loved ones and the numerous benefits of family reunification, as advocated by the European Commission for Human Rights. Health outcomes are improved, kids and young people are more likely to persevere with education, learn new languages and vital skills to support themselves to integrate and contribute within their new society.

One of the mothers said it was the happiest day they’d had in years.

Lord Dubs

Dubs animatedly recalls attending a community funfair in Thessaloniki where a coach of young refugees arrived for an afternoon spent ice skating, driving dodgem cars and playing on trampolines. He talks about watching a coach full of children arrive at a community centre to play with their Greek peers, opening presents and trying ice skating for the first time.

“[The adults] knew it was just an escape for two or three hours, but for the kids it was the most wonderful thing. One of the mothers said it was the happiest day they’d had in years”.

Dubs grins as he talks about the funfair, echoing the sentiment at the heart of the UN’s Convention on the Rights of the Child; kids can be kids when they’re allowed to grow up with their families.

He just wanted to give everyone a big hug. At least now he’s got some chance of a life.

Lord Dubs

Furthermore, he also sings the praises of local councils, community groups and NGOs supporting refugees and asylum seekers coming to the UK, such as Help Refugees and Safe Passage, and Dubs talks at length about how their work is vital in supporting young people, especially those with significant mental health issues.

He talks about a young teenager with learning difficulties who had been kept locked up in a police cell in Greece because the authorities didn’t know how to deal with him. Safe Passage brought the boy to the UK and Dubs met him with his social worker from Hammersmith Council for an emotional reunion in Shepherds Bush Starbucks. “He just wanted to give everyone a big hug. At least now he’s got some chance of a life,” says Dubs.

What’s Stopping us Helping Child Refugees?

A refugee child in a tent on the island of Lesbos, Greece Credit: Steve Evans Flickr

A refugee child in a tent on the island of Lesbos, Greece Credit: Steve Evans Flickr

Despite the clear humanitarian and societal benefits, there are hurdles at every stage of the process to bring minors over, especially when trying to reunite families.

Lord Dubs talks about how relying on the memories of unaccompanied children to identify places and names is difficult. “We’re still members of the EU and we’re trying to push the government to get on with it, and they are being rather slow in identifying the children and doing the process of assessment.”

Details and spellings often get lost in translation, further delaying the already protracted process of identifying and matching children with legitimate relatives settled in the UK. Dubs says that official efforts to work out “whether a Syrian 8-year-old’s Uncle lives in West Bromwich or Wolverhampton” are discarded in favour of fewer but more straightforward matches.

While there is a marked discrepancy between the matching rates of the UK government services compared to the rates of diligent NGOs, reuniting families is in not an impossible task. Dubs talks about how important it is for our government to step up their efforts. “It’s a real problem because the NGOs haven’t got all the time in the world to pursue this but [government inefficiency] is denying these kids a chance,” he explains.

“Brexit has Sucked the Life Out of Politics”

Lord Alf Dubs . Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Lord Alf Dubs . Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Government inefficiency is a sticking point. The UK currently follows the Dublin III regulations to process new refugee arrivals but post-Brexit the UK is no longer obligated to adhere to this legislation. Dubs is committed to ensuring that our government continues to negotiate fairly and advocate for vulnerable unaccompanied minors, especially in the aftermath of the Windrush injustices.

He has persisted with an amendment to the EU Withdrawal Bill to specifically protect the right of unaccompanied children with family in the UK to seek refuge here.

“We had a bit of a success when the bill was going through Parliament, and we got an amendment accepted in the Lords, much against government wishes, and eventually they accepted it. [We just need] to ensure that Britain will negotiate to continue the Dublin III arrangement as if we are members of the EU even after we

Even if we only get a handful more refugees here it is a handful better than zero.

Lord Dubs

Dubs feels that given the myriad difficulties and other problems posed by Brexit, it’s difficult to convince people to prioritise refugee assistance. “Brexit has actually sucked the life out of politics. The fact is we want as good level of cooperation as possible, and the trouble is our relations are perhaps not as good as they might be because of the Brexit business.”

He remains pragmatic though. “I don’t know why it shouldn’t work, because as far as EU countries are concerned surely it’s to their benefit that if there’s a family able to take the kid, as opposed to a kid lying under the trees in Calais.”

Despite the challenges, Dubs is cautiously optimistic and he continues to campaign undeterred, calling on communities and individuals to keep the ongoing refugee crisis in the public’s attention. He is relentlessly lobbying for what he considers to be life-saving, basic humanity in the midst of the crisis.

“Even if we only get a handful more refugees here it is a handful better than zero,” he says, eyes alight.