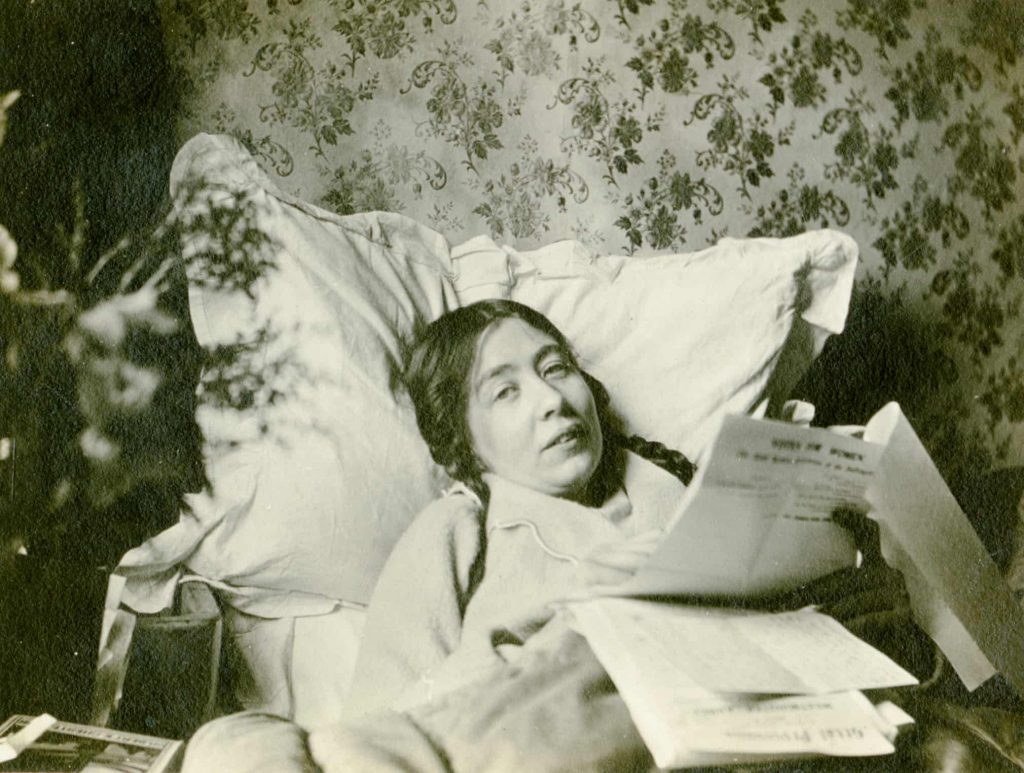

Sylvia Pankhurst, one of Britain’s most famous suffragettes, is propped up in bed with her plaited pigtails falling onto her slumped shoulders. She is leafing through bits of paper as she recovers from hunger strike after being released from Holloway prison in 1913.

This is just one of a collection of over 100 original photographs and documents which reveal in remarkably intimate detail the work of Sylvia Pankhurst, the East London Suffragettes, and life in the wartime East End of London.

This year has been a big one for women in politics all over the world, and February marked 100 years since the Representation of the People Act was passed in Britain.

So it is timely that this month also saw the launch of ‘East End Suffragettes: the photographs of Norah Smyth’ at the Four Corners gallery in Bethnal Green. The exhibition brings back to East London, for the first time, the photographs taken by suffragette Norah Smyth – 100 years after they were taken.

The photographs, letters and documents, all from 1913-1918 and on loan from the International Institute of Social History, capture an extraordinary moment in women’s history.

Who was Norah Smyth?

Norah Smyth was Emmeline Pankhurst’s chauffeur and a highly-skilled photographer. Credit: International Institute of Social History

Although she went on to become one of the most central figures in the East London Suffragettes (ELFS), Norah Smyth in fact started out as a chauffeur to Emmeline Pankhurst, the leading figure of the suffragette movement. It was through driving for Emmeline that Norah met Emmeline’s daughter, Sylvia Pankhurst, who founded the ELFS and became a long-lasting friend.

Their friendship comes through in the exhibited photographs. Norah was a self-taught and highly-skilled photographer, and she used her photographs primarily to promote the work of the ELFS.

Sylvia Pankhurst on Hunger Strike

Sylvia Pankhurst recovering from hunger strike after her release from Holloway prison in 1913. Credit: International Institute of Social History

In one photograph, Sylvia is propped up against a large cushion in bed, her hair in two plaited pigtails, reading letters and newspapers. The photograph was taken in Bow, at the home of Mr and Mrs Payne, where Pankhurst was recovering from hunger strike.

On the back of a different photograph, a note reads: ‘Taken by Miss Smyth the day before I was a mouse.’ Here Pankhurst refers to the so-called ‘Cat and Mouse Act’, introduced by the government to deal with hunger-striking suffragettes. More formally known as the Temporary Discharge for Ill Health Act 1913, prisoners at risk of death through hunger strike were allowed early release, and then sent back to prison once their health had improved.

Sylvia was imprisoned 10 times over 12 months, each time going on hunger strike against forced feeding in prison.

The Woman’s Dreadnought Newspaper

Suffragettes with their copy of the Dreadnought newspaper. Credit: International Institute of Social History

Norah Smyth also largely financed the ELFS’s newspaper, The Woman’s Dreadnought, which was first published on 8 March 1914. The Dreadnought was sold by members of the ELFS for a halfpenny, and a special badge was awarded to ELFS members who sold more than 1,000 copies.

It was the only newspaper of the time to include first-hand accounts written by working-class women, and Smyth’s photographs featured regularly.

The sentiment behind the newspaper’s name is one worth reminding ourselves of today. Sylvia wrote in the first edition: “The name of our paper, The Woman’s Dreadnought, is symbolic of the fact that the women who are fighting for freedom must fear nothing.”

Bringing the Photos Home

Children at the suffragette nursery, the Mother’s Arms. Credit: International Institute of Social History

What is so special about this exhibition is that it is housed in Bethnal Green: precisely where East London Suffragettes were themselves living and operating 100 years ago. Some of the names and landmarks in the pictures will be familiar to many Londoners. The photographs, quite literally, bring everything close to home.

It is also clear from the photographs that Smyth was not simply an outsider with a camera. She was a known and trusted member of the community and the atmosphere of the exhibition reflects that. The photographs themselves are small, but up close, terrifyingly clear and intimate.

Another photograph shows a group of suffragettes hoisting the suffragette flag at 400 Old Ford Road on Sylvia’s 32nd birthday. In the photo, Pankhurst is carrying a little boy and pointing towards Norah’s camera. The boy is the grandson of George Lansbury, the former MP for Poplar and Bow who lost his seat after staging a by-election on women’s suffrage.

One Hundred Years On

A deputation to 10 Downing Street on June 1914. Credit: International Institute of Social History

A deputation to 10 Downing Street on June 1914. Credit: International Institute of Social History

One hundred years later, and 2018 may have been a big year for women in politics, but it’s also been a difficult one, which is what makes a visit to this exhibition even more worthwhile.

We have many triumphs to celebrate, but there is still a long way to go, and the East End Suffragettes will give you a much-needed energy boost: look into the face of Sylvia Pankhurst in turn gazing into the camera; draw upon the energy of women editing the Dreadnought around a kitchen table; and feel the pain of a young girl as she is pepper-sprayed at a suffragette rally.

I challenge you not to come away from the exhibition feeling one of these three things: proud, revived, determined.

Open until 9 February 2018, Tuesday to Saturday, 11am-6pm. Four Corners Gallery, 121 Roman Road, Bethnal Green. Admission is free.