Kaye is a non-binary person who works with trans young people and LGBT victims of hate. As a non-binary person, Kaye does not identify as ‘male’ or ‘female’ and prefers to be addressed with the pronouns of ‘they’ and ‘them’. Here, they explain why reforming the Gender Recognition Act could mean trans people are less likely to experience violence and discrimination.

Reforming the Gender Recognition Act (GRA) is a heated topic and is surrounded by confusion. Changes to the GRA will allow people to change their gender on their passport, driving licence and birth certificate without having to go through complex, expensive and lengthy medical and statutory processes to do so.

I am non-binary. My passport and driver’s licence currently state ‘male’, but my birth certificate ‘female’.

It also has the potential to recognise genders outside of the binary of male or female.

For example, I am non-binary. My passport and driver’s licence currently state ‘male’, but my birth certificate ‘female’.

Both of these options are incorrect.

I would much prefer my true gender of non-binary to be recognised on these identification documents I use daily.

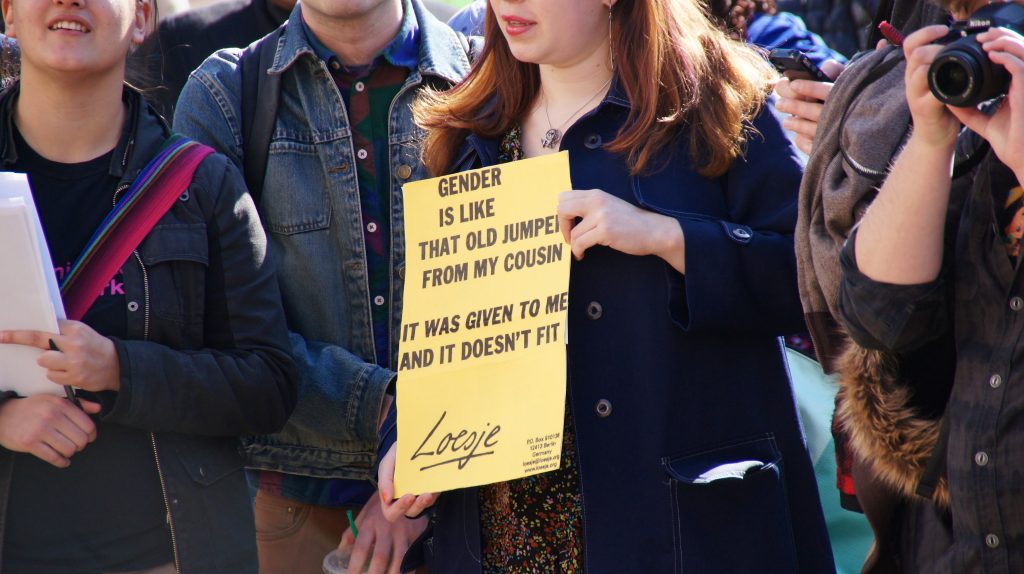

Credit: Ted Eytan Wikimedia Commons

Credit: Ted Eytan Wikimedia Commons

To address the myths surrounding the act: changes to the GRA will not change the Equality Act 2010 which already protects my rights to live a life free from harassment and discrimination.

For binary-identified people it will not change [the fact] that the government sees both their sex and gender as the sex and gender they have transitioned to, including when accessing single sex services in all but exceptional circumstances.

The proposed changes have the potential to be an important step in removing barriers that disproportionately target the most vulnerable in the trans community, giving recognition to genders outside of the male-female binary the government currently enforces, and pave the way for trans people in the future to have a safer journey than the path the government forced me down.

I first realised I was trans at the age of 15 and after years of deliberation at 19 I was referred to a Gender Identity Clinic.

I finally saw a gender identity clinician when aged 22. This is not uncommon – currently the waiting time from referral to first meeting with a gender identity clinician is up to two years in London and up to four years in Exeter.

The long wait had a huge impact on my mental health and left me unable to progress with my life.

The long wait had a huge impact on my mental health and left me unable to progress with my life.

Once within the Gender Identity Clinic system it is not straightforward to change your gender.

There will be at least two meetings, many months apart, before the clinicians will consider a letter that allows you to change your gender on your passport and driving licence to male or female. This letter can then be used to change gender with your bank and doctor’s surgery.

However, just because they can write the letter for a change of binary-gender on documentation at this stage, they do not always do so, especially for non-binary people or people from different cultural backgrounds who have different gender norms.

Myself and many friends have experienced degrading and needless barriers to accessing treatment and letters.

Image via Flickr

They include clinicians requesting letters from unqualified employers stating we are trans; clinicians stating they feel our names are too gendered so must be changed to fit with the clinician’s gender-view; telling us we are not really non-binary and need to wait until we identify as a trans man or woman for support.

For anyone seeking a Gender Recognition Certificate who has managed to navigate the difficult system and received the letters from multiple doctors, they may then have to wait a further two years from being allowed to change their gender on other documentation as the Gender Recognition Panel require two years of evidence in the form of official documentation such as, for example, gender on identification documents or bank accounts.

The most vulnerable within the trans community may struggle to provide this evidence. For example, people who have had to flee domestic violence or who have experienced homelessness are unlikely to have access to copies of these proofs.

Through working in the LGBT sector I have seen people pushed into homelessness due to issues with their identity documents.

Through working in the LGBT sector I have seen people pushed into homelessness due to issues with their identity documents. During the long process to get new documentation I was left living with identification that was strongly at odds with how I presented and how I identified.

This frequently prevented me from being able to do simple things such as going to the cinema to see a 16 or 18+ movie, travel, or go for drinks with my friends as people would not believe the ID matched the person in front of them.

Restricting trans people’s ability to navigate the world has a hugely negative impact on an individual’s life opportunities and mental health. It also means that trans people have to out themselves as trans to their employers, colleges and universities and services they access; this can leave people vulnerable to violence and abuse.†

I was victim to multiple violent attacks for being trans

During my first year at university I was forced to use single-sex female accommodation as I couldn’t get ID showing me as non-binary or male. In these spaces I was victim to multiple violent attacks for being trans.

After leaving university I struggled to get employment with job offers suddenly disappearing after I had to out myself as trans. This is clearly a system that does not work, is needlessly medicalised, overly complicated and leaves people vulnerable to multiple forms of violence.

Credit: Flickr Franziska Neumeister

Credit: Flickr Franziska Neumeister

The changes to the GRA I strongly support are: recognising non-binary identities, allowing people to self-identify without the need of approval by doctors, and have a ‘tell us once’ legally binding policy to prevent abuse of the system.

It is the right for all people to live their life as themselves

At its heart the Gender Recognition Act is a strongly feminist piece of legislation that enshrines the power of bodily autonomy and right to self-definition as being within the hands of the individual rather than the state and medical institutions deciding where you fit within their definitions, which are based on regressive stereotypes and ideas.

It is the right for all people to live their life as themselves and have the structures in place to acknowledge, support and recognise all members of our society.