For many of us here in the UK, access to contraception is easy and free. But this isn’t the case everywhere around the world, with some 214 million women struggling to access vital family planning. But are governments duty bound to provide contraception services? And is there a human right to contraception?

In black and white the answer is actually quite simple. In 2012 the United Nations (UN) issued a report declaring that contraception is a human right. “By Choice, Not Chance,’ goes on to stress that family planning is “universally recognised as an intrinsic right, affirmed and upheld by many other rights.” It adds that it’s vital for both gender equality and women’s equality, as well also helping to reduce poverty – all ideas which link in strongly to our human rights.

In reality, though, things aren’t that simple. Hundreds of millions of women in the developing world have little or no access to their reproductive rights, and it’s a problem in developed countries too, with thousands of unwanted pregnancies every year. So just what exactly are we entitled too?

The Right to Contraception Isn’t New

Image Credit: Chevanon Photography / Pexels

Although it wasn’t until 2012 that the UN specifically set out the human rights argument for contraceptives, this doesn’t mean reproductive rights are anything new. In fact, it was simply a recognition that family planning is already protected by various other international human rights documents.

They point to studies which show how investment in family planning touches on various human rights areas. For example, the right to non-discrimination can be found in all major human rights treaties, such as our own Human Rights Convention and enabling women to make informed choices helps break down inequalities in education, society, and the workplace.

Education itself is a human right and there is also a right to health, something protected by the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The right to life also comes into play here too, with the UN stating that gaps between pregnancies could reduce deaths in childbirth by more than 45 percent.

Writing in a later 2014 report, the UN adds: “Everyone should have access to contraception and the necessary information should also be available to marginalised groups”.

Access to Contraceptives in the UK and Around the Globe

Image Credit: Simone Van Der Koelen / Unsplash

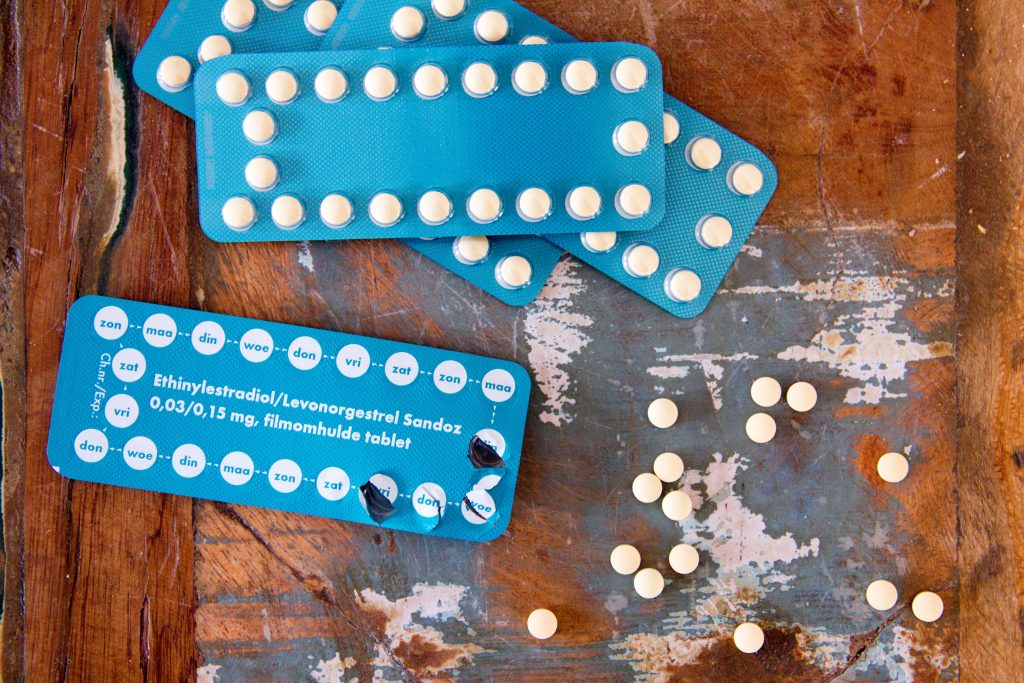

In the UK our right to contraception is fulfilled fairly easily, as most of us are able to access various options for free. Alongside this, the NHS also provides women with easy to understand information about their choices and how they can access them. However, this isn’t the case in every country around the world.

The UN estimates that the lack of availability of contraception services affect 11 percent of sexually active women worldwide between 15 and 49 who either don’t want any more children or would like to delay the birth of their next child. In sub-Saharan Africa, this figure rises to 25 percent.

The World Health Organisation also claimed in July 2017 that 214 million women of reproductive age in developing countries who want to avoid pregnancy are not using a modern contraceptive method.

Why Is This So Important? And What Do We Need to Do?

Image Credit: Max Felner / Unsplash

Image Credit: Max Felner / Unsplash

When the right to contraception is denied it can have severe consequences, particularly in developing countries. For example, some contraceptives like condoms also prevent the spread of HIV and other STIs. Complications in pregnancy and childbirth are also one of the leading causes of death in women aged 15-19 in low and middle-income countries – something which can be more easily avoided if people can choose when to have children.

Allowing people to plan – or prevent – their own pregnancies also means a reduction in the need for abortion, especially relevant in countries where the procedure is unsafe. In practice, this means financially backing family planning programmes, as well as promoting them as part of our human rights. What’s more, it’s not just an issue for women, with more investment needed in education for men and boys.

In their own words, the UN says this means: “Better health for her and her children and greater decision-making power for her, both in the household and the community. When women and men together plan their childbearing, children benefit immediately and in their long-term prospects.”