Torture is forbidden in all circumstances. But where does that absolute prohibition come from? Let’s take a step back and look at the UN Convention against Torture.

Where did it all begin?

The international prohibition of torture goes back to the second half of the 20th century and the birth of human rights. The 1949 Universal Declaration of Human Rights was a milestone in the fight to outlaw torture. It was soon followed by a plethora of other treaties and conventions.

At first, laws outlawing torture were included in general treaties like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Human Rights Convention. Later, the international community realized that more specific instruments were needed, starting with the 1984 United Nations Convention against Torture (CAT).

What is the CAT?

The text of the CAT was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 10 December, 1984. It entered into force on 26 June, 1987. Today, 26 June is celebrated as the International Day in Support of Victims of Torture.

The text of the CAT was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 10 December, 1984. It entered into force on 26 June, 1987. Today, 26 June is celebrated as the International Day in Support of Victims of Torture.

The CAT – which has been ratified by 161 countries – remains the most important piece of international law dealing with torture. It sets out the globally accepted definition of torture and inhumane or degrading treatment. In 2002, the Optional Protocol to the CAT (OPCAT) was adopted by the UN General Assembly. The OPCAT built on the previous treaty, laying the foundations of a torture prevention system.

Since the CAT’s entry into force, the absolute prohibition against torture has become accepted as a principle of customary international law. This means that even if a state hasn’t signed the CAT, they are still expected not to torture.

What does it protect?

The CAT provides protection by stating that torture is always wrong in every circumstance. Article 1 provides a fundamental definition of torture: the intentional infliction of severe suffering, for a specific purpose, by state authorities. Article 2 goes on to state that there are ‘no exceptional circumstances whatsoever’ to justify torture. This means that torture is always absolutely prohibited. Nobody can ever provide a rationale for torture – not even Jack Bauer trying to save thousands of lives from a bomb about to explode.

The CAT provides protection by stating that torture is always wrong in every circumstance. Article 1 provides a fundamental definition of torture: the intentional infliction of severe suffering, for a specific purpose, by state authorities. Article 2 goes on to state that there are ‘no exceptional circumstances whatsoever’ to justify torture. This means that torture is always absolutely prohibited. Nobody can ever provide a rationale for torture – not even Jack Bauer trying to save thousands of lives from a bomb about to explode.

The CAT also spells out many obligations, both positive and negative. First and foremost, states (and their agents) are banned from inflicting torture or otherwise exposing individuals to ill-treatment. For instance, governments are not allowed to deport anyone to a country where they would be at risk of being tortured. States are also required to protect people from real and immediate risks of torture. They must carry out prompt investigations into allegations of torture and provide redress to its victims.

These obligations exist no matter where the torture took place. According to the principle of universal jurisdiction, torture is so serious that national courts can try criminals who committed the offence in another country. Another important facet of the Convention is that it sets down a duty to criminalize torture in national laws. Something that is not the case in certain countries, such as Italy.

However, despite all the ink spilled to unequivocally prohibit torture, it continues to happen worldwide

Is it enforceable?

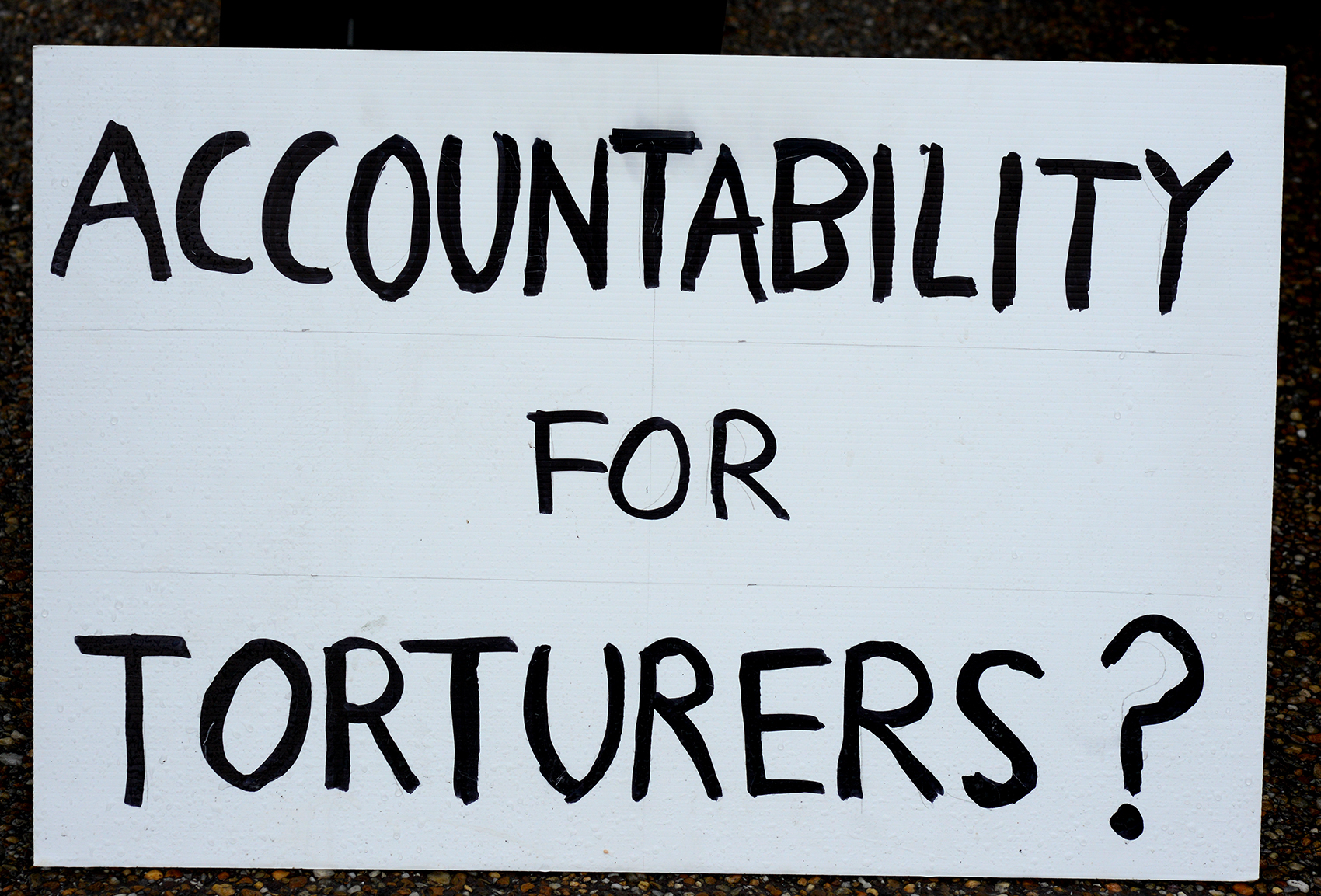

As strong as it is, the CAT has limitations. Its implementation is left in the hands of the state. The Committee Against Torture, which is tasked with monitoring the process, lacks teeth. It cannot impose sanctions against states for failure to carry out CAT obligations. The main mechanism through which the Committee performs its monitoring functions is the reporting procedure. States have a duty to submit a report on the CAT’s implementation every four years. However, although the Committee’s recommendations may have some influence, this does not ensure compliance.

In short, the CAT is an enormous step towards a torture-free world. However, there is still a long way to go.

Want to know more?

- Check out our poster on the right not to be tortured in the Human Rights Convention and our Explainer on why the right not to be tortured matters.

- Learn about how human rights law prevent and remedy torture.

- Read an opinion piece on why we shouldn’t use evidence obtained by torture.

- Learn about how the ‘death row phenomenon’ may amount to torture or inhuman treatment.