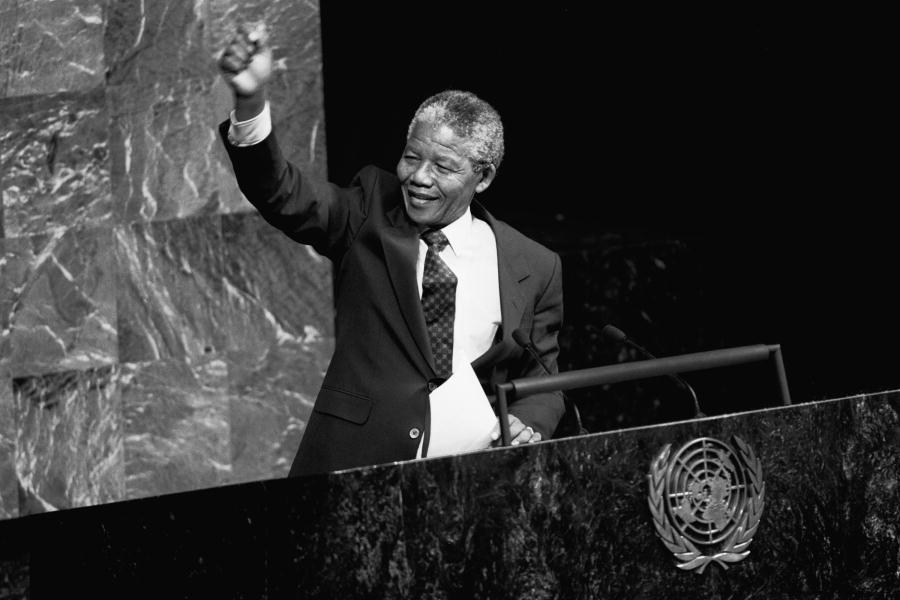

Today is Nelson Mandela International Day. On the anniversary of Mandela’s birthday, this day honours his life’s work and promotes changing the world for the better.

Who is Nelson Mandela?

Nelson Mandela was an anti-apartheid revolutionary and the first President of South Africa.

Mandela was born on 18 July 1918. He was given the forename ‘Rolihlahla’, meaning troublemaker, and in later years became known by his clan name, ‘Madiba’. At school, Mandela was given the English forename ‘Nelson’ by his teacher. When he was 12 years old, his father died and Mandela was entrusted to the guardianship of the regent of the Thembu people. Mandela learned about his ancestors’ resistance of imperialism and apartheid.

What was apartheid?

Apartheid was a system of racial segregation in South Africa. It was enforced through legislation. Under apartheid, the rights and freedoms of the majority black inhabitants and other ethnic groups in South Africa were restricted, and white minority rule was perpetuated.

From 1960 to 1983, 3.5 million non-white South Africans were removed from their homes and forced into segregated neighbourhoods. Non-white political representation was abolished in 1970 and black people were deprived of their citizenship. The government segregated education, medical care and other public services, and provided black people with services inferior to those reserved for white people.

How did Mandela fight apartheid?

At university in the 1940s, Mandela became increasingly involved in politics. He joined the African National Congress (‘ANC’), a political party opposed to the prevailing South African government during apartheid. Mandela helped to form the ANC Youth League and served on its executive committee.

After the South African general election 1948, in which only white people were permitted to vote, the National Party came to power. Mandela and others in the ANC began advocating direct action against apartheid, such as boycotts and strikes. At a rally on 22 June 1952, initiating protests for the ANC’s Defiance Campaign Against Unjust Laws, Mandela addressed a crowd of 10,000 people. He was subsequently arrested, but the campaign established Mandela as a prominent political figure in South Africa.

At this point, the South African government and many in the international community (including US President Ronald Reagan and UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher) considered Mandela’s ANC a terrorist organisation. In July 1963, Mandela and others were charged with sabotage and conspiracy to violently overthrow the government.

From the dock and behind bars

Mandela’s trial gained international attention. Mandela and his associates used the trial to highlight their political cause. On 20 April 1964, facing the death penalty, Mandela made a powerful speech to the court:

I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities.

It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.

On 12 June 1964, the court found Mandela guilty of all charges. Although the prosecution had called for the death sentence, the judge instead sentenced Mandela to life imprisonment.

While in prison, Mandela took part in strikes to improve prison conditions: a small-scale contribution to the broader anti-apartheid struggle. He corresponded with other anti-apartheid activists. In March 1980, the slogan “Free Mandela!”, coined by a journalist, sparked an international campaign. The UN Security Council called for Mandela’s release. A new State President of South Africa, Frederik Willem de Klerk, came to power in 1989. He decided to legalise all formerly banned political parties and announced Mandela’s unconditional release.

The end of apartheid

Mandela was freed on 11 February 1990. In 1991, Mandela was elected ANC President. Unrest continued. Mandela gave many speeches calling for calm and negotiated with the government. In 1993, Mandela and de Klerk were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. A general election was set for 27 April 1994. The ANC won with 63% of the vote. The newly elected assembly’s first act was to formally elect Mandela as South Africa’s first President. Mandela oversaw the transition from apartheid minority rule to a multicultural democracy. The new Constitution of South Africa was agreed in May 1996, enshrining citizens’ rights and setting up institutions to check executive power.

Mandela retired from politics in June 1999, but continued to take part in activism and philanthropy. After a series of long-running illnesses, Mandela died on 5 December 2013 at the age of 95.

Mandela is widely considered the “founding father of democracy” in South Africa. Elleke Boehmer, Professor of World Literature in English at Oxford University, described Mandela as “a universal symbol of social justice“. Mandela has an enduring legacy as the world’s most famous prisoner, a symbol of the anti-apartheid cause, and an icon for millions who embrace the ideal of equality.

Read more about Nelson Mandela International Day. Learn about how human rights protect justice, equality and freedom.