The UK electorate has decided to leave the European Union. It didn’t have to be this way, but it was always likely to happen. Let me explain why, using the human rights debate as an analogy. I will also suggest five key lessons.

First, let me check my privilege. I am not a communications professional or a pollster. I am an human rights advocate, in the courts and in the public sphere. I have set up and run two successful human rights information projects: the UK Human Rights Blog and RightsInfo. I have been in the public advocacy space for a few years now and I think I have learned a few lessons during that time. Here are the lessons from the EU referendum which I think we need to learn urgently:

1. The UK’s media is a huge problem

This may seem obvious, but the most popular newspapers in the UK have, for years, run a very successful public information campaign against the European project, particularly the European Union and European Convention on Human Rights, and of course immigration. In the human rights field, the evidence is very clear. A recent study by CounterPoint found that 70% of reporting about human rights in the UK is from a negative standpoint. In England, it’s 80%.

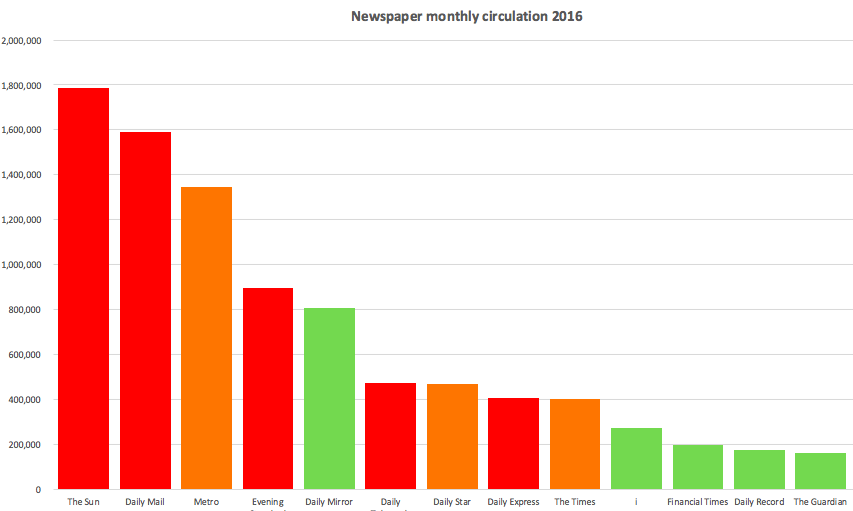

I am fairly certain that the same applies to reporting about the European Union – see The Economist’s useful chart on the distribution of EU myths. The circulation figures matter too. Here is a chart of newspapers’ current circulation. I have crudely coloured each bar to represent where the newspapers sit, in my view, in terms of Europe/Immigration/Human rights. Red is ‘anti’, green is ‘pro’ and orange is somewhere in between:

The above doesn’t capture online figures, but we do know that the Daily Mail is the most popular news website in the world. And here is the thing. The Daily Mail and The Sun are popular not because their readers are stupid or have been lulled into false-consciousness, but because they tell the best stories and employ the best story-tellers. They are brilliantly written and employ excellent journalists. The upshot is that to dislodge the narrative which has been sewn by the popular press, we needed – and still need – a long-term plan to convince people that organisations like the EU work.

One of the most popular moans on social media is about the hostility of the mainstream media. But it does matter. That’s because any attempt to sell the benefits of an institution like the EU effectively starts 5-0 down. Most people have been reading for years how ridiculous and undemocratic the EU is. Overcoming that needs more than a clever digital strategy and funny Facebook films over a few weeks. And myth-busting isn’t the answer. Here’s why.

2. Myth-busting doesn’t work

I have attended countless meetings of civil sector organisations where people despaired at the ambivalence of the British public towards human rights. They would blame the hostile press for poisoning people’s minds. Everyone would agree we need to do instant responses, to myth-bust, to set the record straight. Surely if people know the facts, they would come over to our side?

So I wrote around 50 myth-busting articles. They were popular, with the high-point being Theresa May’s 2011 Conservative Party Conference speech which came to be known as ‘Catgate‘. I felt I was making a difference. But I came to realise that myth-busting wasn’t working, and may even have been making things worse. There is plenty of research to back this up, for example this American study on myth-busting about flu vaccines. The upshot is that myth-busting can work in the sense that putting out accurate information can help move a debate in the right direction. But, people are not that easily swayed. As a social psychologist told the journalist in the article just linked:

“Even if you address specific misperceptions, our motivated reasoning system is going to jump in to fill in the gaps,” Tannenbaum said. “We do a lot to protect the beliefs we already hold, and if one aspect of that belief is challenged, it is easy enough to fill in other reasons.”

Here’s a personal example. RightsInfo has a myth-busting infographic. Each ‘myth’ links to its original source, usually the Daily Mail or Daily Express, and to a source debunking the myth, usually the BBC or UK Human Rights Blog. Each myth really is factually wrong. We conducted some focus groups with ‘middle of the road’ people, i.e. neither politically left or right. Most read the Daily Mail online as their main source of news but also dipped in to the BBC. I watched them use the infographic and the results entirely reflected the research above. When presented with ‘true’ source, they responded with various forms of: well they would say that, wouldn’t they?

The worst thing about myth-busting is that it can reinforce the myths, not the busts. Exposure can give the myths solidity and credence and, as Equally Ours explain, reinforce the negative frames which we are trying to overcome. People remember myths because they are constantly being parroted back. So maybe it wasn’t so clever for David Cameron to focus on the ‘three lies’ of the Leave campaign in the final days before the vote. And this leads me to number 3.

3. ‘Facts’ are not a silver bullet

Since the Referendum result, a lot has been written on us living in a ‘post-fact’ society, where it is useless to tell people the truth because the lies are just as effective. As Michael Gove famously said, “People in this country have had enough of experts”.

I think this is nonsense. If anything, the public has access to better information than ever. And, because of the internet, we can now conduct our own research on complex issues. But the public is rightly skeptical of experts, and in the EU debate the ‘experts’ – particularly economists and bankers – were the same people who failed to predict or prevent the 2008 financial crash. Why should we trust them?

Let’s consider David Cameron’s ‘three lies’: that we give the EU £350m each week, that Turkey is going to join the EU, and the EU is building a European Army. The key point is that none is a complete lie, though each is a huge exaggeration. That matters, because in a febrile debate which was characterised by contestable claims on both sides, each claim probably made a difference in people who were already pre-disposed to believing them anyway. Donald Trump is the master of exploiting this psychological truism.

We are not ‘post-fact’. But many key factual issues in the EU debate were essentially contestable. That meant that it was always going to be difficult in a campaign of just a few weeks, from a starting point that many people were already skeptical, to win on facts alone. So how could the argument be won?

4. Building a liberal culture is just as important as telling people facts

We were never going to win the debate by ‘factsplaining’ (you’re welcome) that immigrants are actually great for the economy and the EU only costs 5p per day per person. The key, to my mind, is building a pro-European, pro-immigration and pro-human rights culture in the UK. This is a long-term project. It means selling liberal ideas using not just facts (immigration helps the economy) but values (immigration is important as it helps people in need). To work, we need a proper strategy which focusses on three basic ideas:

(i) Reframe the debate, don’t just reinforce the existing frames created over a long period by the right-wing press. It won’t be easy. This will take time and money. We need to figure out what has gone wrong with communicating liberal ideals and figure out how to fix the opinion deficit before the next big debate, likely to be over re-negotiation and the British Bill of Rights. It may mean setting up entirely new media sources and creating an army of advocates for liberal ideas. It will mean existing actors need to face hard truths about what they have been doing up to now. It will be painful.

(ii) Focus on the micro, not just the macro. People need to know on a human or values-based level why lofty ideas like international organisations and human rights work for them. These stories don’t come from nowhere: they need to be curated over years and that is what journalists are there to do. If we don’t do this, then the field will be dominated by the stories told by the other side.

(iii) Find the right messengers: It turns out that people didn’t trust David Cameron over the EU. Is anyone surprised? People are not stupid. Before 2016 we have only ever heard him complaining about the exact same things the Leave campaign focussed on. People are annoyed with Jeremy Corbyn for not changing his spots quickly enough to sell the EU to skeptical voters. But Labour got the man it voted for – a Eurosceptic with no reverse gear. Remember, we were 5-0 down. The idea that a group of Eurosceptic leaders could convince a Eurosceptic population to vote Remain was always far-fetched. Before the next debate, we need to figure out who the right messengers are. This leads to my final point.

5. There is still everything to play for

The current panic will pass. Afterwards, we will be left with a similar picture to before. The country is essentially split on Europe, human rights and immigration, notwithstanding the highly effective long-term campaign waged by the right-wing press. Equally Ours and YouGov conducted detailed research on people’s attitudes to human rights. They found that whilst around a quarter of people were ‘pro’ and around the same ‘anti’, most (around 50%) were ambivalent or neutral. I imagine the figures are similar in relation to Europe and immigration.

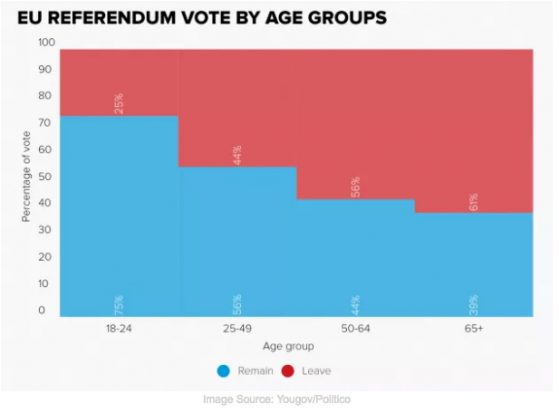

The huge danger here is that the Referendum vote will mark the beginning of the unravelling of liberalism in the UK – if the EU now, why not the European Convention on Human Rights later? But the key is that many people are undecided. In my view, the UK is essentially a liberal country, or perhaps a liberal country which has been mugged by the Daily Mail. It may not seem like it now but this debate can be won in the long term. The most encouraging statistic from the referendum polling was that a majority of younger voters voted for Remain, although that is not to say they will do so in a few years.

We can win the argument, but – and (to paraphrase Boris) I cannot stress this enough – we need to take a long term view, rethink our approach to building a liberal culture, move the focus from factsplaining and myth-busting to building a European culture based on shared values. We can win. But it isn’t going to be easy.

The above is the author’s opinion, not that of RightsInfo