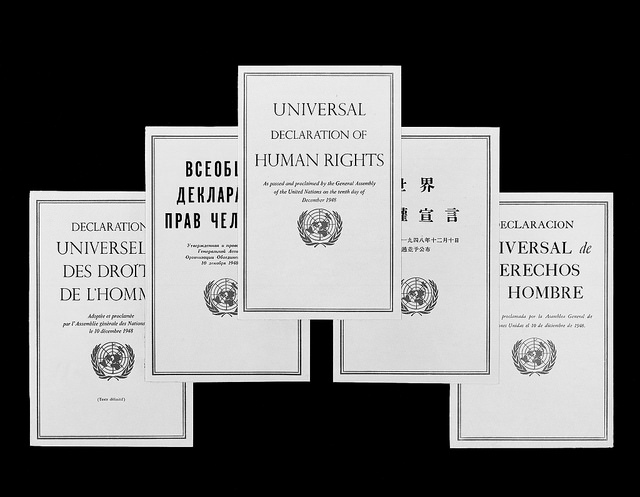

Imagine bringing together high-ranking representatives from 58 countries to secure commitment to a document with 30 key principles. On 10 December, 1948, at the Palais de Chaillot, in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower, the United Nations General Assembly did just that and voted overwhelmingly to adopt the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, with 48 countries voting for it, zero against, eight abstentions and two no-votes.

Described by the chair of the drafting committee, Eleanor Roosevelt, as an ‘international Magna Carta for all mankind’, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), sets out rights and freedoms that all people, wherever they are in the world, are entitled to.

It outlines 30 articles, including the right to privacy and family life, the right to practice a religion (or not), the right to education, the right to a fair trial, and the right not to be enslaved. It also establishes the principle that “all human beings are born equal in dignity and rights.”

The 20th Century’s Single Most Important International Document

Credit: UN Photo

Credit: UN Photo

The UDHR emerged as the world drew breath following World War II and the Holocaust, which saw the industrial-scale murder and genocide of six million Jewish men, women and children by Hitler’s Nazis. Securing the agreement in the aftermath of these horrors was an extraordinary achievement, and seems even more remarkable with the passing of time.

“The Declaration is arguably the 20th century’s single most important international document,” explains Habib Malik, associate professor at Beirut’s Lebanese American University, whose father, Dr Charles Malik, was one of the UDHR’s two ‘principal authors’. “The United Nations Human Rights Committee did its work during a fortuitous crack in history, between the end of the Second World War and the beginning of the Cold War.”

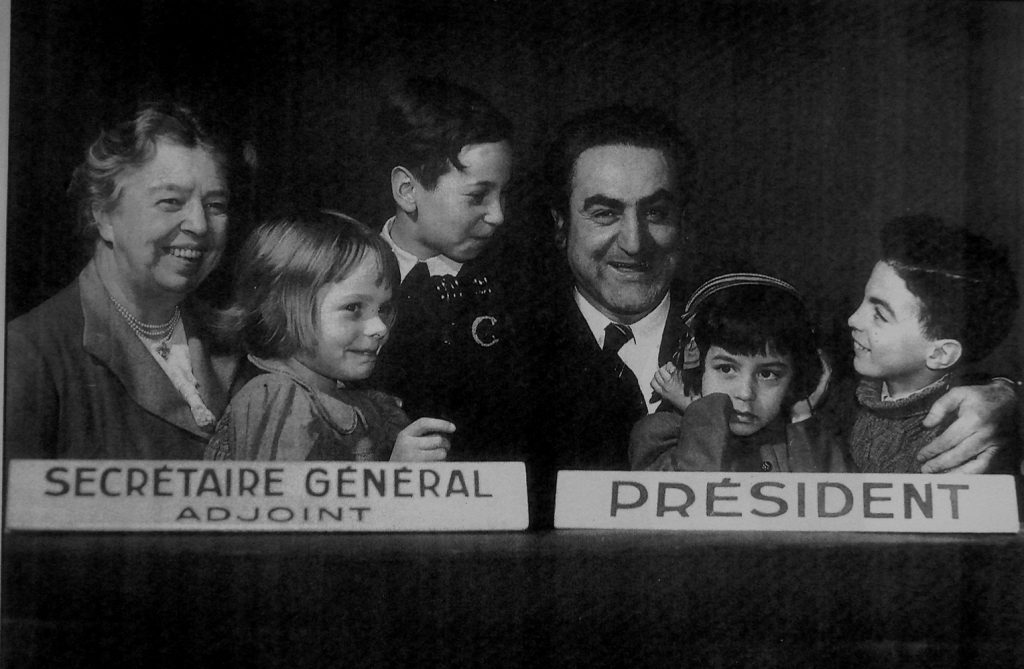

In 1946, that work included commissioning a group of thinkers and philosophers, led by French philosopher Jacques Maritain, to investigate whether there were common global values that could justify a ‘universal’ declaration. They found there were cross-cultural values, enabling a small committee to begin drafting a declaration. This committee consisted of American stateswoman Eleanor Roosevelt, French law expert René Cassin, academic, philosopher and Lebanon’s ambassador to the United States Dr Charles Malik, and Chinese academic and philosopher P.C. Chang.

Eleanor Roosevelt and Dr Charles Malik Credit: Tony Nasralla

Eleanor Roosevelt and Dr Charles Malik Credit: Tony Nasralla

Writing a truly universal declaration was a major undertaking, but canvassing support for it from more than 50 countries with competing interests, worldviews and ideologies, was arguably even more important. Dr Malik, who succeeded Eleanor Roosevelt as Chair of the United Nations Human Rights Committee in 1951, attended meeting after meeting to broker agreement. He also imposed a three-minute rule during discussions to sidestep attempts to delay and derail the UDHR.

There were no negative votes, there were eight abstentions from the Soviet Union and states in their orbit, also Saudi Arabia, and South Africa because of Apartheid.

Habib Malik

“The night before the vote he gave a memorable speech and went out of his way to give every delegation a pat on the back for their contribution, including the Soviets who had given him much grief. He said if it were not for the Soviet delegation we would not have been sufficiently sensitized to economic and social rights,” says Habib Malik.

“He was playing the grand diplomat and did this to ensure to make sure everyone was on board for the vote the next day. There were no negative votes, there were eight abstentions from the Soviet Union and states in their orbit, also Saudi Arabia, and South Africa because of Apartheid.”

The Declaration Establishes Humankind Has Shared Values and Morality

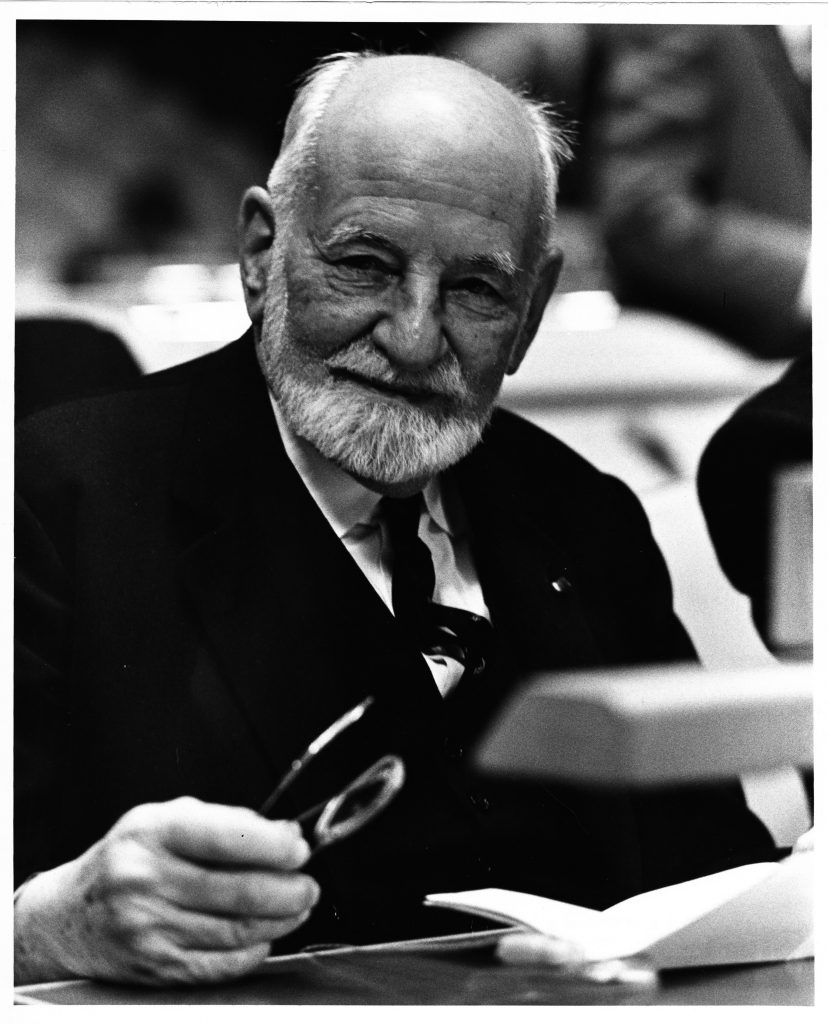

French legal expert René Cassin is often described as ‘the father of the Universal Declaration’ Credit: René Cassin charity

French legal expert René Cassin is often described as ‘the father of the Universal Declaration’ Credit: René Cassin charity

The spirit of cooperation between nations, putting differences aside and looking beyond nationality, race, faith, culture and political ideology, to establish common values for humankind, is both striking and uplifting.

“Charles Malik was a believer in universal values and universal truth and believed they are attainable from reason, he believed the human condition cuts across any cultural specificity,” explains Habib Malik.

Another key figure in the history of the UDHR is French legal expert René Cassin, who is often described as ‘the father of the Universal Declaration‘. Mia Hasenson-Gross, director of the eponymous human rights charity René Cassin, feels the spirit, values and morals of the UDHR are just as notable as the specific articles. “The moral responsibility we have towards each other as humankind is the greatest achievement of the declaration,” she says.

Hasenson-Gross cites the opening sentence of the preamble as an example: “Recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world. Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind.”

“The understanding of the role of human society and the responsibility we carry towards each other reflects René Cassin very much and I have no doubt he was influenced by personal experience – he lost 29 members of his family in the Holocaust,” she continues.

As a charity, René Cassin honours its namesake’s legacy by standing up for human rights. The charity works in the UK on areas including modern-day slavery, indefinite detention and supporting Roma and Traveller communities, a group also persecuted by the Nazis.

It’s the first time, officially, that human rights as we know them today were put down on paper and agreed upon.

Mia Hasenson-Gross, René Cassin

The charity’s work is a powerful example of why human rights are just as relevant today as they were 70 years ago. “We use the Jewish experience and values to understand human rights in our community and look outwards and help others. The Jewish experience is not just the Holocaust, it’s also slavery, detention and discrimination, and our values of freedom, equality, justice and treating the stranger as we would like to be treated,” says Hasenson-Gross.

“The declaration, in my view, is the beginning of the modern human rights framework, it’s the first time, officially, that human rights as we know them today, were put down on paper and agreed upon.”

However, many people still struggle to access human rights. In privileged affluent places such as the UK, Western Europe and North America, the treaties, conventions and legislation that followed the UDHR offer protection against the violation of basic rights.

It’s also abundantly clear that, despite these protections, there are individuals and groups in the same places who face discrimination and inequality on a daily basis. It’s an even more complicated picture globally, where there are countries where the right to a fair trial is non-existent. All too often, freedom of expression and following certain faiths can be life-threatening and lives, particularly for those at the bottom of the pile, are cheap.

Protecting 70 Years of Progress

The first meeting of the eight-member Drafting Committee on International Bill of Rights, UN Commission on Human Rights, 9 June 1947, New York. Credit: UN Photo

The first meeting of the eight-member Drafting Committee on International Bill of Rights, UN Commission on Human Rights, 9 June 1947, New York. Credit: UN Photo

However 70 years on, it’s also important to reflect on just how far we’ve come. Today, the principles of the UDHR are incorporated in the constitutions of 90 countries. In 1948, only nine countries had outlawed capital punishment and women had the vote in just 91. Now, capital punishment is banned in 104 countries and women have the right to vote in 198.

Hasenson-Gross is keenly aware of the progress made since the creation of the UDHR. “I am lucky, as a woman who is a minority, I have been able to fulfil my basic human rights in a way that my grandmother was not able to and I hope the difference between my life and my grandmother’s will be the same for my daughter and me.”

She’s also aware that we must recognise what rights have achieved in order to understand their value. “Recently we were doing workshops with young people about human rights and there was a 15 year old boy asking, why we need the right to life and why is there is an article not to be tortured or enslaved. He couldn’t understand or see a world where that might not happen – it shows that for the majority in the UK, human rights are a default setting, they are always there and we only hear about human rights in extreme cases involving terrorists or prisoners.”

When human rights are at risk, we do all that we can to protect them.

Mia Hasenson-Gross, René Cassin

But rights must be fought for to be preserved. In a chilling echo of 1930s Europe, intolerance and division are on the rise. It’s our duty to come together, just as the world did 70 years ago, to defend human rights and their spirit of cooperation and compassion. Only this will ensure that the unspeakable horrors which prompted the UDHR will never happen again.

“I would much rather live in a society where human rights are taken for granted rather than having to fight for them on a daily basis. We must continue to ensure that this is the default environment and when human rights are at risk, we do all that we can to protect them,’ says Hasenson-Gross.