How human rights fight for women's equality

Today is International Women's Day. Please share this video on why we still need to fight for women's rights

Posted by RightsInfo on Wednesday, 8 March 2017

Human rights are the basic minimum protections which every human being should be able to enjoy. But historically not all people have been able to enjoy and exercise their rights in the same way. The result is unequal treatment.

One such group is women and girls. Throughout history, women have been afforded fewer rights than their male counterparts or have had to work harder to realise their rights in practice. Viewing women’s rights as human rights has been fundamental in the struggle to ensure that women are treated fairly. As part of our series for International Women’s Day, we are taking a look at how women have fought to be put on an equal footing.

1. Women weren’t even people, legally speaking

A British court once actually had to declare that women counted as ‘persons’ in order for them to receive the same treatment as men.

In 1929, a woman named Emily Murphy applied for a position in the Canadian Senate (a house of the Canadian Parliament). She was refused because women were not at the time considered ‘persons’ under section 24 of the British North America Act 1867. This understanding was based on a British ruling from 1876 which stated that women were “eligible for pains and penalties, but not rights and privileges”. Emily Murphy took her case to the Privy Council, the court of last resort in the British Empire.

The judges declared that women were ‘persons’ who could sit in the Canadian Senate. One of the judges, Lord Sankey, said: “to those who ask why the word [“person”] should include females, the obvious answer is why should it not?”

2. Married women were the same legal person… as their husband

In 1765, a famous legal commentator, Sir William Blackstone, wrote that after marriage, the “very being or legal existence of the woman is… incorporated and consolidated into that of her husband”. In other words, a married woman did not, legally speaking, exist separately from her husband.

When a woman married, all of her property was automatically placed under the control of her husband. In 1870, an Act of Parliament allowed married women to keep money they earned and to inherit certain property. In 1882, this was extended to allow wives a right to own, buy and sell property in their own right. In 1893 married women were granted control of any property they acquired during marriage.

Our enjoyment of property is recognised as a human right, subject to certain limitations, under Article 1, Protocol 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

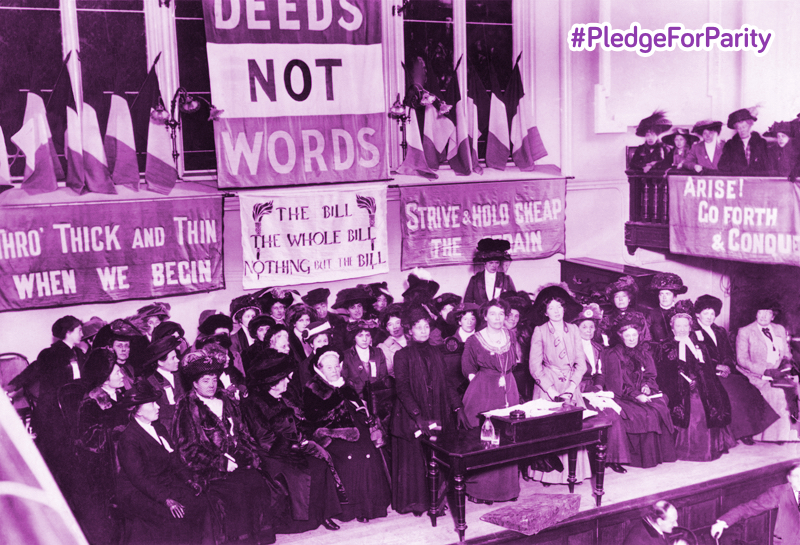

3. Women had to fight really hard for the right to vote

Before 1918, women were not allowed to vote in parliamentary elections. This meant that they had no say in choosing the people who made law, and those law-makers had no political incentive to care about women, since they did not need to win their votes.

Before 1918, women were not allowed to vote in parliamentary elections. This meant that they had no say in choosing the people who made law, and those law-makers had no political incentive to care about women, since they did not need to win their votes.

In the early 20th century, activist groups campaigned for women’s right to vote (‘suffrage’). One such group was the suffragettes. The term ‘suffragette’ was first used by the Daily Mail in 1906. It was intended as a derogatory name for an activist group run by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters. In 1913, suffragette Emily Wilding Davison was fatally injured after she ran up to the King’s horse, racing at the Epsom Derby.

In 1918, the Representation of the People Act first gave women over age 30 the right to vote if they or their husband met a property qualification. The Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act also allowed women to stand for election as Members of Parliament. In took until 1928 (the Equal Franchise Act) for all women in Britain to gain equal voting rights with men.

The right to vote and stand for election are recognised as human rights under Article 3, Protocol 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

4. Women still don’t have access to education

In 1878, the University of London became the first university in the UK to open its degrees to women. In 1880, four women became the first to obtain degrees when they were awarded Bachelors of Arts by the University. Nowadays, millions of women and girls around the world are still systematically excluded from even basic education.

The right to access educational institutions without discrimination is a human right under Article 2, Protocol 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

5. Women had to fight to access their children and plan their families

5. Women had to fight to access their children and plan their families

Before 1839, mothers had no rights at all in relation to their children if their marriage broke down. In 1836, Caroline Norton left her husband, George, who had been abusive towards her. After the separation, George refused Caroline access to their sons. After much campaigning, an Act of Parliament was passed in 1839 giving mothers the right to ask for custody of their children.

In the late 20th century, woman gained greater control over whether or not to have children. Initially, it was a criminal offence in the UK to perform an abortion or to try and self-abort . This led to a high number of unsafe back-street abortions – a major cause of pregnancy-related deaths. To address this, Parliament passed the Abortion Act 1967 to permit abortions under medical supervision and subject to certain criteria. In 1974, contraception also became freely available to all women irrespective of marital status through the NHS.

The right to respect for family life and bodily integrity are protected under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The European Court recently ruled that women in Ireland do not have sufficient access to abortion facilities.

6. Women need legal protection from violence, including in the home

In 1878, the law first said that a woman could obtain an order allowing her to separate from her husband if her husband subjected her to violence. In 1976, an Act of Parliament allowed women in danger of domestic violence to obtain the court’s protection from their violent partner.

It used to be thought that a husband could not rape his wife. But in 1991, rape in marriage was, for the first time, declared a crime. In a court case called R v R, a husband was convicted of attempted rape. He appealed, arguing that, when a woman gets married, she impliedly consents to having sex. The court rejected this, saying implied consent was a “fiction” which “has no useful purpose today in the law”. The case has been used by the European Court of Human Rights to justify gradual, progressive changes in the common law.

Nowadays, female genital mutilation (‘FGM’) is a major issue worldwide, including in the UK. FGM is the dangerous practice of causing injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons. It is typically done for cultural reasons and is prevalent in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. It is estimated that FGM affects 137,000 women in the UK. The practice is illegal in the UK under the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003. It is also now illegal to arrange for a child to be taken abroad for FGM.

7. Women (still) struggle to achieve equality in the workplace

In 1968, women at the Ford car factory in Dagenham took part in a strike for equal pay, almost stopping production at all Ford UK plants. Their protest led to the passing of the Equal Pay Act 1970, though they had to wait until 1983 (the Equal Pay (Amendment) Regulations) for a legal entitlement to equal pay for work of equal value.

In 1968, women at the Ford car factory in Dagenham took part in a strike for equal pay, almost stopping production at all Ford UK plants. Their protest led to the passing of the Equal Pay Act 1970, though they had to wait until 1983 (the Equal Pay (Amendment) Regulations) for a legal entitlement to equal pay for work of equal value.

The Equality Act 2010 consolidated the law protecting women from discrimination on the grounds of sex or maternity in the workplace. In 2016, the government published a consultation on proposals for a law to require certain companies in England, Scotland and Wales to publish gender pay gap statistics.

Protection from discrimination is a human right under Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

So, how far have we still got to go for equality?

In 1977, the United Nations General Assembly declared International Women’s Day an annual event. In 2015, the Word Economic Forum predicted that global gender parity (that is, equality) would, at the current rate of progress, not be achieved until 2133: 117 years from now.

Many women’s rights have been hard won over a centuries-long struggle for equality. Do we have to wait another century before we can finally say women are equal? Take a look at our page on how you can celebrate International Women’s Day and support the #PledgeForParity here