The outbreak of the new coronavirus has been classed as a global health emergency by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

The UK government has declared the epidemic a “serious and imminent threat to public health”, using additional powers to tackle its spread.

The virus is believed to have started in Wuhan, China, and as of early February is estimated to have infected over 40,000 people worldwide – with eight confirmed cases in the UK. The death toll in China has exceeded 1,000 people.

The response to an epidemic can affect the human rights of millions of people across the world, including those in the UK.

Amnesty International has highlighted concerns around the censorship of legitimate news coverage about the virus within China and neighbouring countries.

Meanwhile, activists attempting to share information reported being harassed by authorities.

Here EachOther focuses on the human rights impacts of the evolving response within the UK.

Right To Health

The UK government is obliged to “recognise the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health”.

This is because it has signed the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

This means the government must take steps to ensure the “prevention, treatment, and control” of epidemics.

It is worth remembering this right when considering the government’s obligation towards citizens based in Wuhan – the location of the outbreak, as well as those within the UK.

The Foreign Office has so far chartered two flights to the city, bringing back more than 300 Brits, while some reportedly remain stranded.

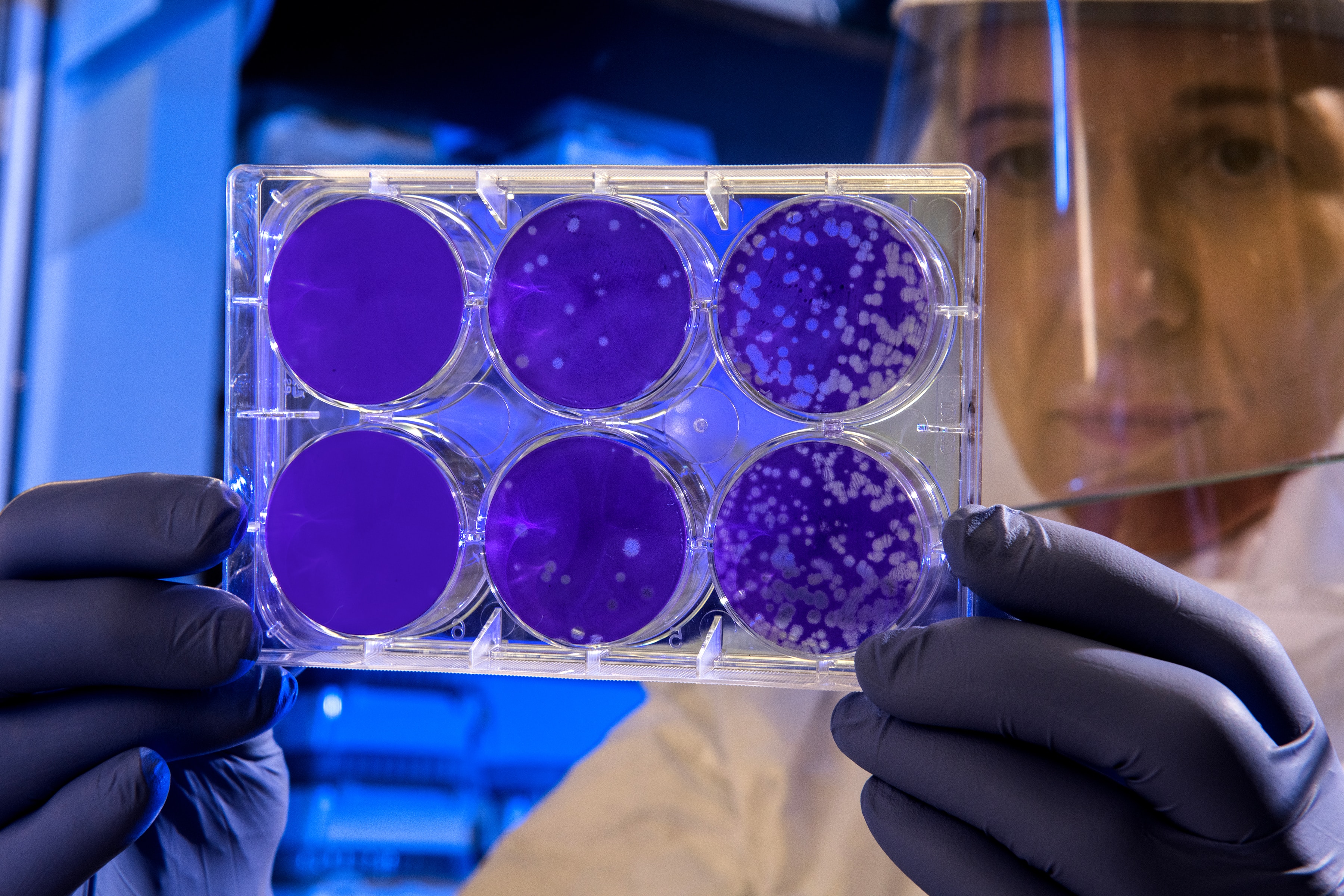

A Scientist examines the result of a plaque assay, which is a test that allows scientists to count how many flu virus particles (virions) are in a mixture. Credit: Unsplash.

The right to health is subject to “progressive realisation” under the ICESCR.

This means the UK must take steps towards achieving this right to the maximum of its available resources. It recognises that it could be hindered by limited resources or that the right may only be achievable over a period of time.

Quarantine

Health Secretary Matt Hancock has announced strengthened powers to “impose restrictions on any individual considered by health professionals to be at risk of spreading the virus”.

This means people in England can be quarantined against their will, if necessary.

People suspected of carrying the virus, such as those returning from Wuhan, are being kept in supported isolation in a centre on the Wirral and another in Milton Keynes.

One person quarantined at the Wirral was “threatening to abscond” from the isolation unit despite signing a contract agreeing to a 14-day quarantine period after returning from Wuhan, according to PA news agency.

Meanwhile, some people who are carrying the virus have been identified as “super-spreaders” – patients who, through no fault of their own, pass on the infection to large numbers of people.

A woman in Tokyo, Japan, wears a mask as she crosses the road. Credit: Unsplash.

Compulsory quarantines, which infringe the right to liberty, can be justified under the Convention of Human Rights. It must be clear the spread of the disease is:

- a danger to public health or safety

- detention is a last resort

- less severe measures proved insufficient.

According to Amnesty International, international law requires that quarantines must be:

- proportionate

- time-bound

- undertaken for legitimate aims

- strictly necessary

- voluntary wherever possible

- applied in a non-discriminatory way

Quarantines must also be imposed in a safe, respectful manner and those under isolation must be protected with access to healthcare, food, and other necessities.

Discrimination and Xenophobia

Asian communities in the UK have reported a shocking rise in racism following the coronavirus outbreak.

Last month, a postgraduate student was reportedly verbally and physically harassed in a Sheffield street for wearing a face mask.

The Manchester Chinese Centre has received reports of children being bullied in schools across the region.

In Leicester, two students who were mistakenly believed to be Chinese were pelted with eggs on the street in Market Harborough.

This xenophobia may have been fuelled in part by sensationalist and misleading media coverage.

For instance, footage of Asian people selling or eating bats, which had been suspected of being the source of the new coronavirus, has circulated on social media and made tabloid press headlines.

It appears that five of the six most-shared videos were filmed outside of China, and none have any documented link to the outbreak, according to France 24.

Nicholas Bequellin, Amnesty International’s regional director, said that: “governments around the world should take a zero-tolerance approach to the racist targeting of people of Chinese and Asian origin.

He added: “The only way the world can fight this outbreak is through solidarity and cooperation across borders.”